A Game of Words: The crash of PSA flight 182

Note: this accident was previously featured in episode 21 of the plane crash series on January 27th, 2018, prior to the series’ arrival on Medium. This article is written without reference to and supersedes the original.

On the 25th of September 1978, hundreds of people watched in horror as a Pacific Southwest Airlines Boeing 727, its right wing engulfed in flames, plunged from the sky over suburban San Diego, California. Simultaneously, the remains of a private Cessna 172 could be seen spiraling down in the opposite direction, before it too disappeared from view. Within moments, twin columns of smoke began to rise up into the cloudless sky, and a neighborhood lay in ruins, its quiet streets transformed into a snapshot of hell.

The collision over San Diego killed 144 people and traumatized a city for a generation. And in the world of aviation, it brought into stark focus the inadequacies of America’s air traffic system. Twenty years after its first major reform, glaring gaps had again presented themselves in the procedures used to keep airplanes apart: in fact, behind all the technology that had been introduced since the start of the jet age, the fundamental means of separation was still the principle of “see and avoid” — the notion that pilots would see each other in time to avert any collision. This concept still exists today, but the crash of PSA flight 182 in San Diego would mark a turning point in the way the aviation industry thought about it. But change would not come immediately — first, one rogue investigator would have to go on the record urging a greater reckoning than his colleagues were willing to endorse.

Although it is today but a glimmer in the eye of an older generation, Pacific Southwest Airlines, based in California, was once America’s largest low-cost carrier. Known for its red, white, orange and sometimes pink color schemes and the playful smiley faces painted under the noses of its planes, the airline cultivated a carefree Californian image, which it sought to associate with sunsets over the ocean and good times on the beach. Thirty-four years after its demise, however, it is perhaps most closely associated with a photo of a burning plane plunging from the sky, a photo which resonated around the world at the time and which still captivates us today.

◊◊◊

The 25th of September, 1978 was a beautiful early autumn day in Southern California — what San Diegans would call a “Santa Ana” type day, with the temperature already surpassing 27˚C (80˚F) by 8:00 in the morning. The weather was perfectly clear, a great day for flying.

Earlier that morning, PSA flight 182, a three engine Boeing 727, departed Sacramento, California, en route to San Diego with a stopover in Los Angeles. In command were three experienced pilots: 42-year-old Captain James McFeron and 38-year-old First Officer Robert Fox, who had a combined 24,000 flying hours; and 44-year-old Flight Engineer Martin Wahne. They were joined by four flight attendants and 128 passengers — although 30 of those were actually off-duty PSA employees riding along, or deadheading, to San Diego. One of them was Captain Spencer Nelson, who sat with the pilots in the cockpit, occupying the observer’s jump seat.

After an uneventful trip from Sacramento, flight 182 departed Los Angeles at 8:34, and was scheduled to arrive in nearby San Diego in about 30 minutes. The flight proceeded normally, as the 727 rose briefly to its cruising altitude before descending again, making contact with San Diego approach control and receiving clearance to begin its approach at 8:57. The atmosphere in the cockpit was relaxed, as First Officer Fox flew the plane, Captains Nelson and McFeron conversed back and forth about their jobs and finances, and Flight Engineer Wahne talked with the company about some paperwork. Captain McFeron was not supposed to talk about non-operational topics while below 10,000 feet, but this rule had only been put in place three years earlier, and in those days it was still routinely violated.

However, by 8:59, the conversation had ended as the pilots transitioned to their approach checklist. It was then that the San Diego approach controller called them and said, “PSA 182, traffic twelve o’clock, one mile, northbound.”

“We’re looking,” Captain McFeron replied.

Moments later, the controller contacted them a second time. “PSA 182,” he said, “additional traffic’s, uh, twelve o’clock, three miles, just north of the field, northeastbound, a Cessna 172 climbing VFR out of one thousand four hundred.”

Sitting directly ahead of them, the Cessna was easy for the PSA pilots to spot. “Okay, we got that other twelve,” First Officer Fox said, keying his own mic.

This airplane was a standard single-engine Cessna 172 belonging to Gibbs Flite Center, a flight training company operating out of nearby Montgomery Airport. On board was 32-year-old instructor pilot Martin Kazy Jr., who was teaching a certified pilot, Marine Sergeant David Lee Boswell, to fly using only his instruments. Boswell was wearing a training hood, designed to prevent him from seeing outside the plane, while Kazy kept watch both on the trainee and on the skies around them.

After departing Montgomery Field, the pair had made two instrument approaches to runway 9 at San Diego’s main airport, then known as Lindbergh Field, before breaking off to the northeast and heading back toward Montgomery. The San Diego approach controller had told them to stay below 3,500 feet and assume a heading of 070 degrees, which would cause them to cross in front of the PSA jet, probably at a lower altitude, although they were still climbing.

Just after 9:00, the approach controller decided to check again to make sure the PSA crew knew to keep clear of the Cessna. “PSA 182, traffic’s at twelve o’clock,” he repeated, “three miles, out of one thousand seven hundred.”

“Got ‘im,” First Officer Fox said, again easily spotting the Cessna.

“Traffic in sight,” Captain McFeron reported to the controller.

In the background, Flight Engineer Wahne jokingly reported to the company, “San Diego Ops, PSA 182 is number two [for landing] because we try harder.”

Simultaneously, the controller said, “Okay sir, maintain visual separation, contact Lindbergh tower 133.3, have a nice day now.”

“Okay,” McFeron replied.

By instructing the crew to maintain visual separation, the controller was conveying his belief that the pilots had the Cessna in sight and would take any necessary maneuvers to avoid it without his input. But did the pilots understand that? On this point, doubt remains.

Contacting the tower, who would handle the final phase until landing, Captain McFeron said, “Lindbergh, PSA 182, downwind.” He meant that they were on the “downwind leg,” the segment of the approach before the 180-degree turn to line up with the runway for landing.

“PSA, Lindbergh tower,” said the new controller, “traffic twelve o’clock, one mile, a Cessna.”

This was the same plane as before, but, unbeknownst to the PSA crew, it had deviated from its assigned heading of 070 degrees, embarking on a right turn to 090 degrees instead — the exact same heading as flight 182, and the much faster Boeing 727 was rapidly closing on it from behind.

“Is that the one we were looking at?” asked McFeron.

“Yeah, but I don’t see him now,” said Fox.

“Okay, we had it there a minute ago,” McFeron said to the controller.

“182, roger,” the tower replied.

“I think he’s pass(ed) off to our right,” McFeron added.

In this critical exchange, several things happened. Internally, the pilots of flight 182 had acknowledged to one another that they could no longer see the Cessna in front of them. According to proper procedure, when under an instruction to maintain visual separation, they were required to tell the controller if they no longer had the traffic in sight. But not only did McFeron not explicitly say this to the tower, he actually ended up giving the controller the false impression that he knew where the Cessna was. By what could only be described as a freak twist of fate, the word “passed” sounded like “passing” when it was heard in the control tower. When interpreted with the word “passing” in the present tense, the statement seemingly indicated that the crew was actively watching the Cessna, when in fact McFeron meant that the Cessna had already passed behind them. This belief was refuted by the controller’s radar display, meaning that McFeron must not have had the smaller plane in sight after all if he was wrong about its position.

However, the tower controller, in the course of his duties, relied far more on his own eyes than on his radar screen, which, unlike the approach controller’s, could not display an aircraft’s altitude anyway. Having gained the impression that the pilots of flight 182 were aware of their position relative to the Cessna, he turned his attention to other duties. Unknown to both him and the pilots, the Cessna was in fact lurking right under the edge of the 727’s windscreen, still trundling along directly in the path of the jet, which was rapidly bearing down on it from behind and above.

Aboard flight 182, the pilots continued to search for the plane. Captain McFeron said, “He was right over here a minute ago…”

“Yeah,” said First Officer Fox. Twenty seconds later, he added, “Are we clear of that Cessna?”

“Supposed to be,” said Flight Engineer Wahne.

“I guess,” said McFeron.

“I hope,” said Nelson, from the observer’s seat. His comment was punctuated by laughter.

At that moment, a traffic conflict alert began to sound in the approach control center, located at Miramar Naval Air Station. The alert sounded whenever two planes were projected to pass within 375 feet vertically and 1.2 nautical miles laterally within the next 40 seconds. The approach controller observed that the alert pertained to PSA flight 182 and the Cessna, but of these he was only talking to the latter, having handed flight 182 over to the tower moments earlier, and he had already assured the Cessna pilots that the PSA crew had them in sight. It was difficult for him to tell whether separation between them was actually a concern: the conflict alert went off on average 13 times a day, usually spuriously, and by now the two planes’ targets on his radar display were so close together that their altitude readouts overlapped, rendering them unreadable. According to proper procedure in the event of a conflict alert, he was required to ensure that the conflict had been resolved, either by determining there to be no conflict, by issuing an instruction to the Cessna, or by calling the tower and telling them to issue an instruction to the PSA plane. In this case, having previously heard from the PSA crew that the Cessna was in sight, he decided that no conflict existed, as the PSA pilots would surely not fly into a plane that they could see.

Unfortunately, the conflict alert was real, and neither pilot could actually see the other. With the controller’s failure to issue a warning, a collision became all but inevitable.

It was at that moment that First Officer Fox suddenly said, “There’s one underneath.” He paused, then added, “I was looking at that inbound there.”

Perhaps Captain McFeron got up to look, but he was too late. “Whoop!” he shouted, trying in vain to avoid the Cessna.

“Aargh!” Fox screamed — and then the planes collided.

The 727, overtaking the slower Cessna from behind, plowed directly into it with tremendous force. The 727’s right wing all but ripped the little single-engine plane apart in midair, throwing pieces in every direction and killing both pilots instantly. The impact also tore away nearly ten meters of the leading edge of the 727’s wing, along with even more of its trailing edge. The Cessna’s fuel tank lodged in the wing, its contents mingling with fuel liberated from the 727’s own tanks to form a raging inferno.

Aboard the 727, the pilots felt a massive jolt, and then the plane immediately began to bank to the right.

“Oh god damn!” Nelson shouted.

“Easy baby, easy!” said McFeron.

The plane was rolling ever more steeply to the right, pulled down by the enormous damage to its lifting surfaces. The wing’s aerodynamics were ruined, and multiple flaps and slats, critical to low speed flight, were now falling to earth alongside the remains of the Cessna. Control of the plane was rapidly becoming impossible.

“What have we got here?” said McFeron, trying to get a handle on the damage.

“It’s bad!” said Fox, trying in vain to level the plane. Despite turning his yoke fully left and pulling nearly full nose up, the plane was still pitching down and rolling right, accelerating toward the ground.

“Huh?” said McFeron.

“We’re hit man, we are hit!” Fox shouted.

Keying his mic, McFeron broadcast a frantic distress call. “Tower, we’re going down, this is PSA!”

“Okay, we’ll call the equipment for you,” the controller replied, but it would be of no use.

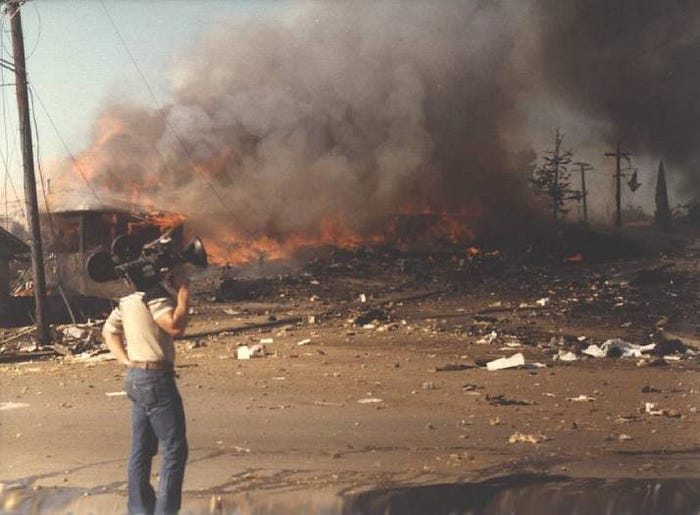

On the ground, witnesses watched in stunned disbelief as the plane, its right wing consumed in flames, arced through the sky over San Diego’s North Park neighborhood, clearly out of control. One of them was Hans Wendt, the chief photographer for San Diego County. Training his lens on the falling airliner, he captured two photos that would shock the world.

On the plane, it had become clear that the end was nigh. “Whoo!” someone screamed. A stall warning blared as the right wing continued to lose lift.

“Bob!” another person shouted.

First Officer Fox unleashed a string of expletives.

“This is it, baby!” said McFeron. “Brace yourself!”

“Hey baby!” someone shouted.

“Ma, I love ya!”

These would be the last words captured on the cockpit recorder. Two seconds later, pitched fifty degrees nose down and banked fifty degrees to the right, PSA flight 182 slammed into the intersection of Dwight and Nile Streets in San Diego’s North Park neighborhood. The right wing sliced the roof off a house, and then the main body of the aircraft exploded against the street, sending an unstoppable wave of flaming debris directly into a row of houses. In a matter of seconds, the tide of riven debris traveled a distance of nearly two blocks through the quiet suburban neighborhood, setting numerous houses aflame in an instant. By the time the wreckage came to a halt, little remained of the Boeing 727, no less than 22 houses had been damaged or destroyed, and two dark columns of smoke were rising above San Diego, twin beacons of disaster that could be seen for miles.

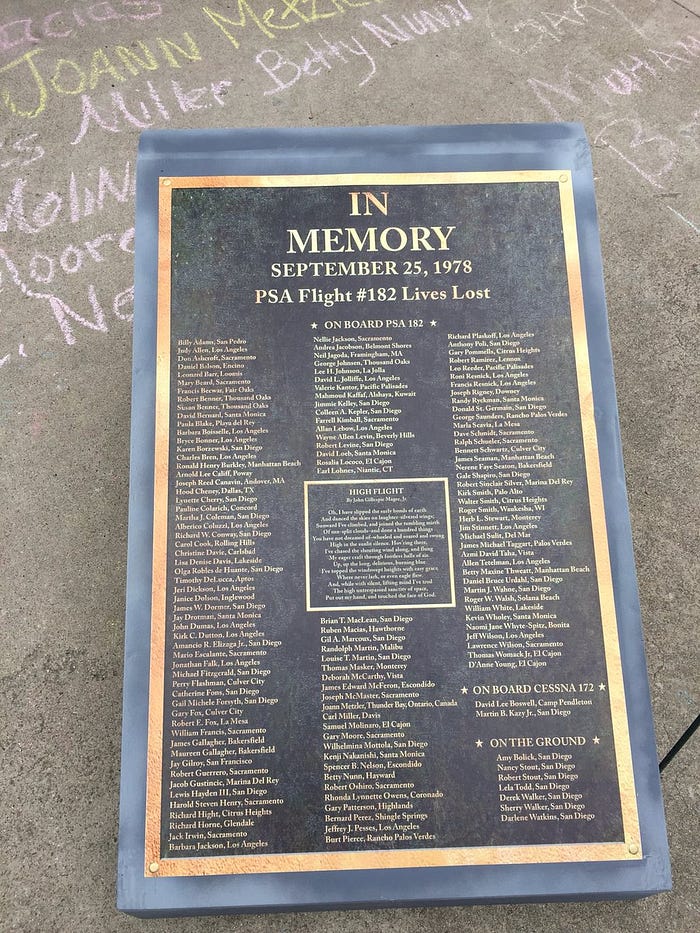

For those aboard flight 182, there was no possibility of survival; all 135 passengers and crew died instantly on impact. So did the two pilots aboard the Cessna, most of which fell near the intersection of 32nd and Polk, although various smaller pieces of the unfortunate aircraft and its occupants were scattered over a much wider area.

The toll was also heavy on the ground in the vicinity of Dwight and Nile. The jet obliterated a day care center, killing owner Nancy Stout and her four-year-old son Robert; Cheryl Walker and her three-year-old son Derek, who had just pulled into the driveway, were also killed, along with three others in nearby houses. Not far away, a mother and her baby narrowly escaped death when a body slammed into the windshield of their car, showering them with glass, and a young man on a skateboard dodged the aircraft itself by the narrowest of margins. They would be among the lucky ones, by virtue of their very survival. First responders, upon arriving at the scene minutes later, were forced to confront those who had been less lucky: indeed, bodies and body parts were everywhere, in people’s yards, in wrecked cars, on the roofs of houses, mixed in with pieces of the plane, which had been launched for several blocks in all directions. It was a grisly sight, one which many would wish to forget.

Although hospitals across the region prepared for an influx of patients, it was clear as soon as paramedics arrived at the scene that there were very few victims for them to save. Nine people on the ground were injured, but 144 others lay dead, including everyone on both planes and seven more residents of North Park. At the time, it was the worst air disaster in American history, breaking a record that had stood for nearly 18 years — although, tragically, its own record would be far surpassed a mere eight months later.

The magnitude of the disaster, regardless of its high death toll, was no doubt magnified by the terrifying photographs of the plane in flight, which soon appeared on the front pages of newspapers across the country. The disaster, and the unprecedented way in which it was documented, made manifest the nightmares of both air travelers and the public at large. Not only did passengers wonder whether they were safe, so did people who simply lived near busy airports. Could planes really collide at any time? Was it safe to live under a flight path? And why was the existing system unable to prevent the catastrophe?

Answering these questions, as usual, fell to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). They considered three main lines of inquiry: why the pilots of the two aircraft did not avoid each other, why controllers did not avert the collision, and why the pilots of flight 182 did not regain control of their airplane.

Regarding the last question, little remained of the right wing which could reveal the extent of the damage it suffered. However, Hans Wendt’s photographs provided a number of useful clues. Although the wing was on fire and missing several large sections, investigators noted that the ailerons were at their full extension, indicating that hydraulic power was present to move them, and that the pilot’s application of full left roll was unable to stop the plane from banking right. Considering this evidence, it seemed that at least some hydraulic systems remained intact, allowing the control surfaces to move unimpeded, but control was nevertheless impossible due to the right wing’s severely compromised aerodynamics. Unable to keep their right wing flying, there was nothing the pilots could do to prevent their plane from spiraling into the ground.

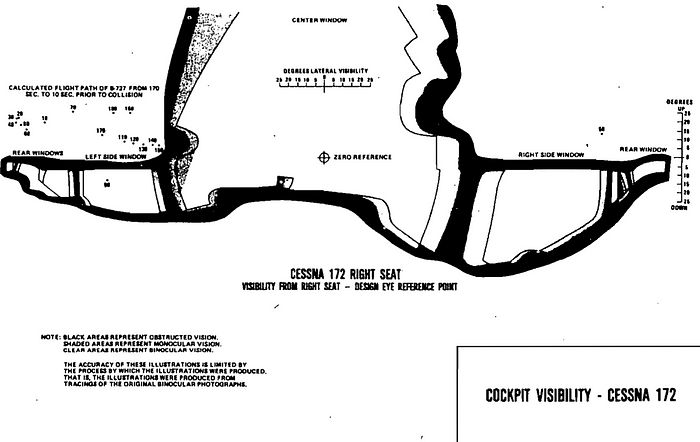

The question of whether the pilots could have, or should have, seen each other required the NTSB to plot the planes’ positions in three dimensions and assess where they were in each other’s fields of view during the critical two minutes before the collision.

According to these calculations, there was never any real chance for the Cessna pilots to have seen the 727 coming. The jet was only visible in the far corner of their windscreen for ten seconds; otherwise, it was behind and above them the entire time. They were warned of the presence of the PSA jet, but were told that the 727 had them in sight. Besides, as the overtaking aircraft, it was the responsibility of the PSA crew to avoid the Cessna, a fact of which the Cessna pilots were well aware. In fact, right up until the moment of the collision, they would have believed that the PSA pilots were taking the necessary steps to keep clear of them.

In contrast, the Cessna should have been within the PSA pilots’ field of view for the entire period before the collision. In fact, during the first 90 seconds of this period, it was right in the middle of the pilots’ windscreens, where it should have been plainly visible, and indeed the pilots spotted it without difficulty. However, as the 727’s deck angle increased in response to the deployment of the flaps and the resulting decrease in speed, the Cessna moved down toward the bottom of the windscreen, near the wipers. It seems that it was at this point that the pilots lost track of it.

However, during testimony from PSA’s chief pilot, the NTSB learned that PSA pilots frequently did not adjust their seats to align their eye level with the manufacturer’s recommended line of sight. Many pilots reported that from this position it was more difficult to see some of the instruments, and they preferred to move the seat at least one inch (2.54 cm) farther back and slightly downward compared to the recommended settings. From this position, it would not have been possible to see the Cessna without leaning forward. And to make matters worse, the Cessna was proceeding in the same direction as flight 182, rendering it motionless against an extremely complex background including many colors and angular shapes that would have made the small plane very difficult to distinguish. As such, it was explicable, if not necessarily inevitable, that the pilots lost sight of it.

Here, the NTSB noted that under existing rules, the pilots were obligated to immediately inform air traffic control that they could no longer see the Cessna. As mentioned earlier, this was because the controller had instructed them to “maintain visual separation” from the traffic, making the pilots solely responsible for avoiding the specified aircraft. Controllers routinely deferred this responsibility onto crews who said they had traffic in sight, and this situation was by no means unusual. However, the pilots did not clearly articulate when they lost track of the Cessna, an error which was exacerbated by confusion between the words “passed” and “passing,” ultimately preventing the tower controller from recognizing that the PSA pilots could not see the traffic and that the only active means of separation had thus broken down.

The significance of this fact requires some appreciation of the varying levels of what air traffic control experts call “separation;” that is, the means by which safe distances between aircraft are ensured. The most basic means of separation is “see and avoid,” which is largely self-explanatory. Backing up “see and avoid” is positive radar separation, wherein air traffic controllers monitor airplanes on radar and provide them with advance instructions to avoid a loss of separation, even if they cannot see each other. However, in 1978 it was common for air traffic controllers to defer responsibility for separation onto pilots who had each other in sight, even if it was possible to continue providing positive radar separation as well. In the NTSB’s view, this represented an unnecessary and potentially dangerous degradation of the redundancy in the system, especially given that “see and avoid” as a concept had been considered flawed since at least the 1950s.

The fact that the pilots involved in the collision lost sight of each other while under “see and avoid” rules, and the proper steps to return to radar-based separation did not occur, underscored the danger inherent in giving up positive radar separation in the first place. This put both the tower controller and the approach controller, each of whom was speaking to just one of the aircraft involved, in a position where they presumed separation was ensured by someone else. When the conflict alert went off in the approach control center, the approach controller could have taken positive action to prevent a collision, but he believed that the pilots had already done so, without being able to actually verify this as they were no longer on his frequency. On the other hand, had he continued to properly monitor the flights on radar even after the PSA pilots said they had the Cessna in sight, the collision most likely could have been prevented. In the NTSB’s opinion, it would therefore be best practice for controllers to tell pilots if they are involved in a conflict alert, or tell another controller who can tell them, regardless of whether they believe the conflict is serious or not.

Differences in expectations between pilots and controllers also complicated the situation. Even though controllers sometimes deferred responsibility for separation onto them, pilots generally assumed that controllers would continue to monitor them on radar and would say something if safe separation was lost. In reality, this was often not the case. This simultaneous relaxation of vigilance by both pilots and controllers was widespread in the air traffic system and presented a potentially deadly risk.

Furthermore, when maintaining visual separation from another aircraft, PSA pilots were told that half a nautical mile laterally was an acceptable safe distance, even though this was well within the 1.2-nautical-mile threshold which would trigger a conflict alert in the San Diego approach control center — a fact which partially explained why controllers received so many false or marginal alarms every single day.

Part of the problem was that there was no description of ATC methods that was required reading for both pilots and controllers. Pilots did not normally read the ATC manual, and although the FAA-issued Airman’s Information Manual did attempt to reconcile the two sets of procedures, this was not required reading either.

Yet another issue which came up during the investigation was whether the presence of an unidentified third aircraft could have misled the PSA pilots. This notion was supported by the First Officer’s statement, “I was looking at that inbound there,” uttered moments before the collision. Had he been watching some other airplane? And if so, which one?

Adding to the speculation, 16 separate witnesses reported seeing a third plane in the area at the time of the collision. However, these witnesses varied wildly in their descriptions of the plane, its location, and direction of travel, and some of them were in fact describing a Grumman T-Cat light aircraft which arrived over the scene only after the accident had occurred. Furthermore, controllers were not speaking to any other aircraft in that immediate area, there were no other aircraft “inbound” at that time, and radar records did not divulge any suspicious tracks that could be an aircraft that failed to announce itself to air traffic control. Due to an absence of evidence, the NTSB concluded that the First Officer’s statement most likely could not have referred to another airplane which he mistook for the Cessna.

One last factor which did contribute to the collision was the Cessna’s unexplained decision to turn onto an easterly heading of 090 degrees, deviating from its assigned heading of 070 degrees without telling the controller. Had this turn not been made, the two planes would have crossed paths with at least 1,000 feet of vertical separation. Instead, they ended up on the same heading, with the PSA jet overrunning the Cessna from behind. Without any kind of cockpit voice recorder aboard the small plane, the NTSB was not able to determine why this turn occurred or even whether it was on purpose. But there was no doubt that if it was intentional, the pilots of the Cessna should have informed air traffic control, and they did not.

Taking all these conclusions together, quite a lot could have been said, and indeed was said, about the systemic factors leading to the crash. However, the NTSB’s final probable cause statement, as was often the case in that era, took a very narrow view of fault, placing responsibility mainly on the PSA pilots for failing to properly inform the controller when they lost sight of the Cessna. Inadequacies in air traffic control procedures were cited as the sole contributing factor.

This portrayal of the accident did not sit well with all the board members who were responsible for the investigation. Although three signed off on the probable cause, a fourth refused to do so: veteran investigator and serial dissenter Francis McAdams, who was well known for taking his colleagues to task over excessively narrow determinations of fault. At that time (and to some extent, still today), probable cause statements are required by definition to place disproportionate weight on the last, most proximate cause, a practice which often elevates errors by individual people over the systemic deficiencies that made the accident possible in the first place. Seeking to challenge the traditional thinking, McAdams argued that since the collision most likely would not have happened if controllers had not needlessly deferred to visual separation when radar separation was possible, then the procedures which allowed this to occur should have been elevated to the level of probable cause alongside the pilots’ errors.

But McAdams wanted to go much farther than that, too, arguing for a reversal of traditional thinking about separation. “In my opinion,” he wrote, “the concept of see and avoid is outmoded and should not be used in high-density terminal areas.” Rather than treating “see and avoid” as the primary means of separation in all situations, while radar separation is seen as a form of redundancy, he argued that positive radar separation should be the primary means of defense and the pilots’ eyeballs should be secondary.

In addition to this, he listed a number of other factors which contributed to the accident but were not cited by the NTSB as contributing factors. These included the Cessna pilots’ unannounced deviation from their cleared course; the tower controller’s failure to mention the Cessna’s direction of travel (a required item) in his last traffic advisory; and the fact that the two planes were talking to different controllers while in the same airspace, a disturbing fact mentioned in the NTSB’s final conclusions but which was not otherwise discussed in their report at all. Furthermore, he rebutted an argument put forth in the NTSB report which contended that the approach controller had resolved the conflict alert per his responsibilities. The argument was that the conflict was in his view resolved because the PSA pilots had told him the Cessna was in sight. However, in McAdams’ opinion, an acknowledgement of “traffic in sight” received a full 66 seconds earlier while in a highly dynamic traffic environment simply was not proof that the conflict had been resolved. As such, the approach controller contributed to the accident by not taking further steps to verify that the two planes actually had each other in sight and were not in conflict. And lastly, he argued that there was no other obvious explanation for the First Officer’s statement about an inbound aircraft except that another aircraft was indeed present, unknown to ATC. Therefore, he wrote, the possibility that such an aircraft existed could not be excluded, and should be cited as yet another contributing factor.

As a result of McAdams’ dissent, the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) petitioned the NTSB to accept his version of the probable cause and contributing factors. In 1982, a majority of the board agreed with the petition, and all but two of McAdams’ positions were officially adopted by the NTSB in a revised report. Thanks to his persistence, the public and the industry were provided with a more nuanced understanding of the events which led to the crash.

In its report, the NTSB also issued several recommendations intended to prevent future midair collisions, including that controllers not defer to visual separation unless a pilot requests it; and that Lindbergh Field, as well as other airports wherever appropriate, develop so-called terminal radar control areas — zones inside of which all aircraft receive positive radar-based control and must be equipped with the necessary technology (specifically, a transponder capable of broadcasting altitude) to make this positive control possible. These recommendations led to the implementation of such zones at many more airports across the United States, and led to the adoption of positive radar control as the default means of separation near major airports, even if pilots are engaged in visual separation at the same time. And the crash also spurred some of the earliest development of what would become the modern Traffic Collision Avoidance System, or TCAS, which automatically warns pilots in advance of a collision even with no input from air traffic control.

All of these developments, however, would be unable to prevent tragedy from striking one more time. In August 1986 — after the implementation of most of the aforementioned changes, except for TCAS — a private Piper Archer collided in midair with an Aeromexico DC-9 over Los Angeles, killing 82 people, including all 67 on both aircraft and 15 more on the ground. The parallels to PSA flight 182 were not lost on anyone. In this case, however, even the new measures put in place after the PSA crash failed to prevent the collision, as the small private plane, which was not equipped with the correct transponder and was not in communication with air traffic control, strayed into the terminal area and plowed into the DC-9 while the controller was distracted with another aircraft. Only after this repeat tragedy would traffic collision avoidance systems be required in the United States, and eventually around the world.

Today, the skies around major airports are much more tightly monitored than they were in 1978, as controllers have access to an abundance of data that they can use to prevent separation problems before they arise — and on the rare occasions when they do, pilots no longer have to rely solely on “see and avoid,” as TCAS now provides a third layer of redundancy. As a result, there has not been a midair collision in the US involving an airliner since Aeromexico flight 498 in 1986.

For those who still live under the flight path into what is now San Diego International Airport, these changes provide some comfort. But few who were there that day will forget the horror that befell their city, from the firefighters who responded, to the students whose gym was used as a morgue, to the ordinary citizens who suddenly feared that their neighborhoods could be next. To be sure, even some of those who moved into the reconstructed houses near Dwight and Nile were and still are unaware of what took place there, as there is little to mark the site, save for a subtle change in the local architectural style. One would never think that this utterly normal residential street was once the scene of such unimaginable horror, that 144 people met their end on that very spot, for it is not a lonely or dismal place, but a piece of San Diego’s urban fabric, which has, in time, healed alongside its people. And so today we are privileged to walk those streets in peace and say, “never again.”

_________________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit!

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 200 similar articles.

You can also support me on Patreon.