A Long Night in Coventry: The crash of Air Algérie flight 702P

On the 21st of December 1994, an Algerian cargo plane crashed into an electrical transmission pylon on approach to Coventry, England, sending the Boeing 737 plunging into a forest with the loss of all five crewmembers. Although the plane clipped several rooftops as it went down, no houses were directly hit and no one on the ground was hurt. Local residents called it a miracle, but the plane never should have been there at all — in fact, it had descended well below the minimum descent height, under conditions of thick fog, without the slightest comment from the seemingly oblivious crew.

As for how they got there, that was a superficially simple story with a complicated background. The ill-fated 737, operated by Algeria’s flag carrier, had been hired by a UK-based company called Phoenix Aviation for the controversial shipping of live veal calves for slaughter in Europe, a practice that had drawn vociferous public opposition. Many UK-based companies refused to do the work, as a result of which Air Algérie became involved — only to provide a plane with outdated equipment, a crew who lacked critical training, and an organizational structure without flexibility or oversight. These systemic deficiencies nearly led to crashes on multiple previous occasions, until an unlucky crew, faced with uncompromising weather, a difficult approach, and 10 straight hours on duty through the night, finally toppled the house of cards. It was left to British investigators to pick up the pieces — and the damning story they uncovered would leave virtually no one unscathed.

◊◊◊

In 1994, a moral fervor swept the United Kingdom, compelling thousands to take to the streets of normally sleepy British seaside towns. The protestors were standing up for creatures with no voice: specifically, newborn calves on their way to be turned into veal, a popular element in several European regional cuisines. For some protestors, the production of veal itself was likely the issue, but for many, their concern focused narrowly on the conditions in which the calves were raised and transported prior to slaughter.

Around 1993, it became economical for British cattle farmers to export calves to Europe for slaughter due in part to the relaxation of trade regulations associated with the formalization of the European Economic Community. Combined with a decreasing number of abattoirs in Britain, these incentives led to a massive increase in the shipping of calves, often in restrictive crates without food or water, through public-facing ports of entry where sympathetic citizens became aware of the practice. Protests against the export of veal calves were ad-hoc and locally organized, but they quickly garnered national attention and achieved considerable success in blocking the movement of calves through several British ports. Before long, ferry companies that had been accommodating live animal trucks announced that they would stop accepting any further shipments, and exporters were hounded from one port to the next as they fled mounting opposition.

In August of 1994, as public displeasure continued to build, an unspecified UK-based livestock trading company approached a British air transport broker called Phoenix Aviation with a proposal to export veal calves to continental Europe by air. Despite its name, Phoenix Aviation owned no airplanes and did not have an Air Operator Certificate, although its managing director was a qualified Boeing 707 pilot. Instead, Phoenix Aviation brokered deals between companies seeking to transport cargo, and a network of airlines from Africa with which it had contractual relations.

Information about Phoenix Aviation is scant — they had little or no public presence — but according to the AAIB accident report, the company consulted the International Air Transport Association’s guidelines for live animal carriage and determined that a Boeing 737–200 was the optimal airplane for shipping the veal calves.

News that Phoenix Aviation was looking for a 737–200 cargo plane for livestock transport soon reached Air Algérie, the state-owned flag carrier of the North African nation of Algeria. The airline was not picky with its contracts; it had livestock handling experience; and its pilots were trained in the UK and were familiar with European airports, making the company an ideal candidate. Sensing opportunity, Air Algérie offered to supply one of its converted Boeing 737–200 freighters, registration 7T-VEE, along with several flight crews, for a mid- to long-term contract.

Phoenix Aviation accepted Air Algérie’s offer, and a contract was signed, effective October 20th, under which Air Algérie was responsible for the aircraft, crew, maintenance, and insurance, while Phoenix Aviation would cover fuel, taxes, fees, ground handling, and crew accommodations. The contract also included a fixed cost per flight hour and a guaranteed minimum utilization.

However, the contract also held that the flights must operate under a flight number associated with the charterer, in this case Phoenix Aviation, in order to ensure that overflight and landing fees were properly allocated. This stipulation was included despite the fact that Phoenix Aviation didn’t have an Air Operator Certificate (AOC) and thus could not possibly be the legal “operator” of the aircraft, which is the party that determines the flight number. Available documents don’t explain why the contract was written this way. But to get around the provisions, Phoenix Aviation turned to a perennial business partner, the Ghana-based freight company Race Cargo Airlines. A separate contract was signed in order to operate the flights under Race Cargo’s AOC, using that company’s callsign “FASTCARGO” instead of “AIR ALGERIE,” even though Race Cargo Airlines was not involved in the operation in any way. This questionable arrangement had no effect on the eventual tragedy, but it did exemplify the conditions under which the aircraft would be operated.

As I previously discussed in my recent article on HA-LAJ, under Article 88 of the United Kingdom Air Navigation Order of 1989, a company wishing to hire a foreign air carrier for operations on British soil was required to obtain special permission from the Department of Transport. (The previous article concerned permissions for “aerial work” specifically, but a similar process was required for non-scheduled cargo operations.) In its application to the DOT, Phoenix Aviation listed Race Cargo Airlines as the operator of the aircraft, but 7T-VEE was not registered to Race Cargo’s AOC or its insurance, a discrepancy that drew scrutiny during the review process. The DOT ultimately ordered this issue to be corrected before granting the flight operations permit, but Phoenix Aviation encountered lengthy delays acquiring the necessary paperwork from Algeria and Ghana.

When October 20th rolled around and the contract came into force, 7T-VEE was ferried to the United Kingdom and began carrying live veal calves as arranged, even though final approval of the operating permit was still pending. The DOT International Aviation Directorate apparently sent repeated faxes to Phoenix Aviation reminding them that operating without an article 88 permit was illegal. However, available documents don’t suggest that any attempt at enforcement was made, nor was the Civil Aviation Authority made aware of the violations. In fact, the CAA was unaware that 7T-VEE was even in the country.

After the aircraft arrived in the UK, operations initially commenced out of Bournemouth, but strong local opposition soon forced a last-minute shift to Coventry Airport, southeast of Birmingham. The official report mentions some unspecified “legal action” that took place in connection with the move, but I was unable to determine the details. It’s possible that local opponents of live animal exports filed suit to stop the activities and that Phoenix Aviation prevailed, but I was not able to confirm this. The operation indeed encountered some opposition in Coventry, with near daily protests at the airport, during which demonstrators attempted to block livestock trucks from entering the premises despite a heavy police presence. In fact Coventry Airport would later become the scene of the only protestor fatality during the popular movement, when a young woman was run over while attempting to stop a delivery in February 1995.

Phoenix Aviation and Air Algérie planned for 7T-VEE to make a round trip between Coventry and one of three European airports — Nantes or Rennes in France, or Amsterdam in the Netherlands — approximately every four hours, on the half hour, almost around the clock, to transport the contract quota of 5,000 cattle per week. Several Air Algérie flight crews were positioned at a hotel in Coventry to rotate shifts, with each crew spending one to two weeks in the UK before returning home.

Coventry Airport was served by a single main runway, designated 05 from the southwest or 23 from the northeast, with a usable length of only 4,600 feet (1,400 m), which restricted the 737–200’s takeoff weight to well below the theoretical maximum. However, for the short range flights and low cargo density associated with the livestock operation, this was sufficient.

A more significant problem became apparent only after operations began, when pilots discovered that they were unable to lock on to the instrument landing system (ILS) for runway 23. Because this was the only ground-based approach aid available at Coventry Airport, its unserviceability presented a serious obstacle to operations when the weather was poor — which, given that this was Britain in November, was very often.

Air Algérie flight crews were well aware that the problem with the ILS was on their end, because other aircraft were using it without any issues. Amid concern about the viability of the operation during the winter months, the company contacted Air Algérie’s flight operations department by fax in search of information about the ILS receivers installed on the plane, but they received no meaningful response.

An instrument landing system emits two overlapping signals, the localizer and glideslope, which can be detected by specialized ILS receivers on board an aircraft to help it align with the runway and follow the optimal glide path. When ILS technology was originally standardized, these signals were broadcast within a frequency band between 108.1 and 111.9 MHz, on odd channels only (108.1, 108.3, etc), for a total of 20 possible channels. The idea behind the sequestration of each type of emitting technology within a specified frequency band is to prevent pollution of important frequencies by unrelated signals, but this can, and often does, result in a particular form of emitting device outgrowing the frequency band originally allotted to it. By the 1970s, the density of instrument landing systems in some parts of the world had increased to the point that the number of available channels became a limiting factor preventing the installation of further such systems. In order to install more instrument landing systems in areas where all 20 channels were already in use, aviation authorities began encouraging the adoption of newer, more precise receivers that could accurately track frequencies separated by 0.05 MHz, rather than 0.1 MHz. With this technology, 20 additional channels were opened, each located 0.05 MHz above an existing channel within the allotted frequency band, for a total of 40. The United States implemented a 40-channel standard for ILS receivers in 1973, and the International Civil Aviation Organization followed suit in 1976.

When 7T-VEE was manufactured by Boeing in 1973, it was fitted with an old style 20-channel ILS receiver. The aircraft was delivered directly from the factory to Air Algérie prior to the 40-channel standard coming into force in the United States, and although it was possible to modify the receiver to the updated standard, Air Algérie never did so, probably because there was no need for the extra ILS channels in Algeria.

Twenty-one years later, Phoenix Aviation discovered that this outdated receiver was why 7T-VEE couldn’t receive the ILS at Coventry Airport, which broadcast on a frequency of 109.75 MHz. In order to prevent delays, Phoenix Aviation eventually stopped waiting for a response from Air Algérie management and acquired a 40-channel ILS receiver all on its own, which was then fitted by Air Algérie mechanics in the UK. However, flight crews immediately discovered that the problem had not been solved, as they were still unable to receive the ILS in Coventry. Unsure why their solution had failed, Phoenix Aviation returned the receiver to its seller and put the old one back in. Apparently no one appreciated that the 40-channel receiver wouldn’t work as advertised unless the aircraft was fitted with an accompanying 40-channel control box, which it wasn’t.

Under UK regulations at the time, there was no requirement that an aircraft engaged in non-scheduled cargo operations be fitted with an ILS receiver at all, so in strictly legal terms this outdated equipment was a non-issue. But in practice, the problem significantly increased pilot workload by forcing crews to use a rare Surveillance Radar Approach, or SRA, whenever visibility at Coventry was restricted.

In a typical instrument approach, pilots use ground-based navigational aids to either align with the runway, align with the glide path, or both, permitting a landing under conditions when the runway is not visible until late in the approach. An SRA, however, is performed exclusively using verbal guidance provided by an air traffic controller with reference to a radar display. In a typical SRA, the controller will make a continuous radio transmission throughout the final phases of the approach, during which they will provide headings to maintain alignment with the runway, as well as reference altitudes typically correlated to a standard 3-degree glide path. The pilots will follow these directions while descending at their discretion or with reference to the altitudes provided by the controller, until reaching a minimum descent altitude (MDA) or height (MDH) specified on their approach charts. If, having reached both the MDA(H) and a designated “missed approach point” (MAPT) without seeing the runway, then the flight crew is obligated to go around. The locations of the MDA(H) and the MAPT depend in part on the distance from the runway threshold to the so-called “termination point,” where the controller ceases to provide further instructions and the crew is expected to locate the runway visually. At Coventry Airport, SRAs terminating at 2 nautical miles, 1 NM, or 0.5 NM from the runway threshold were available, depending on the visibility. When visibility was low, an SRA terminating closer to the runway would be used.

Surveillance radar approaches are typically used only when no other approach method is available and traffic is sparse. Although they are covered in training, most pilots are unlikely to encounter one in the wild. An SRA is not really any more difficult to fly than other non-precision approaches (that is, approaches without vertical guidance) but certain misunderstandings can arise simply due to a lack of practice.

Unfortunately, the operation of 7T-VEE was not unmarred by errors and deviations. The Air Algérie flight crews caused a number of incidents at Coventry Airport, including events in which the aircraft lined up on an active runway without clearance; failed to comply with altitude clearances after takeoff; or did not adhere to navigation instructions. The incidents were put down to the crews’ unfamiliarity with the area and a relative lack of English language proficiency. No reports were filed to the CAA, which remained unaware that the operation even existed.

◊◊◊

By the end of November, 7T-VEE had been flying out of the UK for a month and the DOT permits were still pending. Furthermore, the permit application was only for flights in October and November; no application was ever submitted for flights in December. And yet the operation continued.

On December 18th, a new crew arrived in Coventry from Algeria for a regular rotation, consisting of 44-year-old Captain Ahmed Nemdil, 35-year-old First Officer Nasreddine Hantour, and 38-year-old maintenance engineer El-Hachemi Abdellaoui. The two pilots both had about 2,000 hours on the 737, although Captain Nemdil had over 10,600 hours of total experience to Hantour’s 2,800.

The crew completed two trips between Coventry and Rennes on December 19th, followed by a 27-hour break before two scheduled round trips to Amsterdam on the 21st. Also scheduled on the Amsterdam trips were two British livestock handlers, consisting of 22-year-old Andrew Yates and 31-year-old Adrian Sharpe, whose job was to ensure the welfare of the calves during the flight.

The schedule facing the two pilots that day met all applicable duty time requirements, but it was still rather gnarly. The first flight was scheduled to leave at 00:30 on the 21st, and if all went according to schedule, they would arrive back at Coventry after the second round trip at around 07:30, having flown through the night. A 27-hour rest break followed by a 7-hour night shift was completely legal, but operation through the hours of circadian low immediately following a transition from a day shift to a night shift will inevitably result in a certain level of fatigue — especially if the flight encounters any delays.

Unfortunately for this crew, delays started piling up from the very beginning. After being taken to the airport at 23:45, loading delays resulted in a departure at 00:59, almost half an hour late. The first flight to Amsterdam was otherwise uneventful, and the livestock was unloaded normally. The crew then flew the empty aircraft back to Coventry, where they completed a surveillance radar approach to runway 23, terminating at 1 NM, and landed at 03:42.

After loading a second batch of livestock, the aircraft departed again at 04:52, arrived in Amsterdam, and repeated the process. Taking advantage of lower fuel prices in the Netherlands, the crew stocked up on fuel, enough to complete not only the flight back to Coventry but also the next scheduled flight to Rennes. This time, however, the empty return flight promised to be less straightforward. During the first approach to Coventry that morning, the reported visibility was 20 km with scattered clouds at 4,500 feet, and the crew easily spotted the runway before reaching the minimum descent height. But this time, the terminal aerodrome forecast for Coventry had markedly worsened, predicting a visibility of 800 meters in fog until 09:00. By the time the flight departed Amsterdam at 06:42, the observed visibility had in fact decreased to this value.

Around 45 minutes later, 7T-VEE made contact with the Coventry approach controller, who offered a surveillance radar approach to runway 23 terminating at 0.5 NM. However, she also reported that the runway visibility range (RVR), which refers to the distance over which a pilot can see the runway lights, was only 700 meters.

According to the official United Kingdom Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP), the minimum RVR required for an SRA at Coventry was 1,100 meters. Furthermore, the flight crew were using approach charts supplied by Jeppesen, which followed US standards for determining minimums, resulting in an even higher minimum RVR of 1,500 meters. In many parts of the world, including the United States, regulations apply a blanket minimum visibility to certain approach categories, and enforcement of the (possibly higher) minimum visibility or RVR specified on an approach chart occurs at the discretion of individual airlines. As a result, in these countries it may be legal to attempt an approach even if the visibility is below minimums, on the off chance that the approach is successful. But in the United Kingdom at that time, it was forbidden for flight crews to attempt an approach if the reported RVR was below the minimum used by their company, regardless of what that minimum was. Within the UK aviation industry, this rule is widely known as the “Approach Ban,” but foreign pilots flying to the UK were not always aware of the regulation, and it’s unknown whether the crew of 7T-VEE had any knowledge of it.

Air traffic controllers do not know the minimums used by every airline that might visit their airport, and they have no authority to deny a request for an approach on the grounds of visibility as long as the airport is open. However, when a foreign airline applied for permission to fly to the UK, it was supposed to provide the CAA with the Aerodrome Operating Minima (AOM) in use by the company for each destination and alternate airport, for the purpose of approach ban enforcement. Air Algérie had submitted this information for Heathrow and other nearby airports in connection with its scheduled passenger service between Algiers and London, but no AOM data was filed for the cargo operation involving 7T-VEE. As a result, no one was actually monitoring whether the aircraft complied with the approach ban or not.

Even if the flight crew knew about the approach ban, however, it’s also not clear that they knew the minimum RVR for an SRA at Coventry. In the Jeppesen charts used by Air Algérie, the minimum RVR values for all possible SRAs at UK airports were provided in list format in the back of the booklet rather than on each SRA chart itself. The full booklet was not actually available to the crew — instead, Phoenix Aviation had provided a “trip packet” featuring only airports that were likely to be used during the operation. This trip packet was later destroyed in the crash and it was not possible to verify whether the list of minimums from the back of the book was included.

Possibly as a result of these factors, the flight crew agreed without question to the controller’s offer of an SRA to runway 23, and the crew followed the procedure more or less to the letter.

At that time there were two permissible ways to fly a non-precision approach lacking vertical guidance, known colloquially as the “continuous descent” and “dive-and-drive” methods, respectively. Historically, the latter method was most common. In a dive-and-drive approach, the flight crew descends as quickly as possible to the minimum descent altitude/height for the approach and then flies level until the runway becomes visible, or the missed approach point (MAPT) is reached and a missed approach is initiated, whichever comes first. However, this method has a number of drawbacks, including the requirement to make a last-minute transition from level flight to descent after seeing the runway, as well as the risk of striking the ground far from the airport if the crew is too slow to level off at the MDA. As a result, by 1994 airlines around the world were increasingly turning to the continuous descent method, in which flight crews establish a speed and descent rate that will approximate a three-degree glidepath that reaches the MDA at the missed approach point.

At that time, Air Algérie’s operating manuals still recommended the outdated dive-and-drive method, but to the pilots’ credit, they used the continuous descent method during the approach to Coventry that morning. After aligning with the runway under air traffic control guidance, they adhered to the three-degree glidepath until reaching the missed approach point, whereupon they failed to see the runway through the fog and a missed approach was duly initiated.

After executing the missed approach procedure, 7T-VEE was given vectors to fly to the Coventry non-directional beacon (NDB) for holding, where it remained for nine minutes while the flight crew requested the latest weather information for their alternate airports. Nearby Birmingham turned out to be almost as socked in as Coventry, but visibility at East Midlands Airport in Leicestershire was reportedly well above minimums. After consulting with Phoenix Aviation, the pilots reported at 07:49 that they had been instructed to divert to East Midlands.

In response, the Coventry controller instructed them to remain in the holding pattern until they had coordinated handoff of the aircraft with the Birmingham area control center and the East Midlands aerodrome. The flight crew correctly read back this instruction, but to the controller’s great surprise, at 07:53 the aircraft departed the holding pattern and began flying in the direction of East Midlands without clearance. The Birmingham and East Midlands controllers were forced to intervene to prevent traffic conflicts, prompting both controllers to file incident reports with the CAA. This would be but the first of several baffling errors that suggest the pilots’ performance was beginning to slip after eight hours on duty through the night and early morning.

After being cleared for an ILS approach to runway 27L at East Midlands, the crew discovered that they couldn’t receive the frequency for that ILS either, but due to the good visibility they managed to spot the runway from 8.5 miles out and executed a visual approach instead. By 08:08, they were on the ground.

Phoenix Aviation looked into the possibility of loading the next shipment of livestock directly at East Midlands, in which case the flight crew could retire to the hotel. But this turned out not to be possible, so the crew remained on duty, waiting for conditions in Coventry to improve so they could ferry the aircraft back to base. Complimentary breakfast was provided for all five crewmembers while they waited.

At 09:00, a Phoenix Aviation representative in Coventry saw that the meteorological conditions were improving, as predicted by the forecast, so they asked the tower to relay the numbers. The weather observer responded with a visibility measurement of 1,200 meters with an overcast ceiling at 600 feet. These numbers were then passed on to the flight crew. The values were already close to or above the minimums for an SRA to runway 23, and with further improvements expected, Captain Nemdil decided to accept Phoenix Aviation’s recommendation that he proceed to Coventry. Again, nobody recognized that the reported visibility remained below the Jeppesen minimums, and that an approach could violate UK law.

After gathering the crewmembers and completing the pre-flight, 7T-VEE departed East Midlands at 09:38, operating as flight 702P, with the “P” indicating that this was a positioning flight. The straight line distance from East Midlands Airport to Coventry Airport is only about 28 nautical miles, and the anticipated flight time would have been little more than 15 minutes. As a result, the flight was cleared to a cruising altitude of just 4,000 feet before being given vectors directly to the Coventry NDB. The crew subsequently accelerated to a cruise speed of 280 knots, which was typical during a normal flight but was wildly out of proportion with the distance they were flying. Like many countries, the UK imposes a speed limit of 250 knots below 10,000 feet. Furthermore, flying at such a high speed would have compressed the already tight timeline even further. The fact that the crew did not appreciate this again raises the specter of fatigue.

As a result of the compressed timeline, the after takeoff checklist was completed in cruise flight, and the descent/approach checklist was initiated immediately afterward. One of the items on the approach checklist was the approach briefing, during which the crew would review the approach procedure and the applicable minimums. However, Captain Nemdil simply read off “approach briefing reviewed,” even though no approach briefing was heard on the cockpit voice recording before or during the flight. For extremely short flights, the best practice is to brief the approach prior to departure, but there’s no evidence that the crew ever did so.

The flight remained in contact with Birmingham center in cruise flight for only three minutes before being transferred back to the same Coventry approach controller who provided the first SRA earlier that morning. After identifying the aircraft on radar, the Coventry controller advised that she would provide the flight with vectors to the ILS approach to runway 23, and they were cleared to descend to 1,500 feet on a heading of 090˚, or due east. A turnback would then be performed to align with the southwest-pointing runway 23. The crew did not mention at this stage that they were unable to perform an ILS approach.

Commencing the turnback maneuver, at 09:45 the controller instructed flight 702P to turn to a northeasterly heading of 030. With First Officer Hantour at the controls, Captain Nemdil read back, “Ace Cargo seven zero two papa, we turn left heading zero eight zero.” The controller started to correct him, then modified the clearance to 010.

“Roger, turn right to zero one zero,” Nemdil read back, even though this heading was to their left. These multiple readback errors were again suggestive of flight crew fatigue.

Recalling that this aircraft had previously requested surveillance radar approaches, the controller now asked, “Seven zero two papa, are you able to take up the ILS at Coventry now or would you like an SRA?”

“Ah sorry, confirm your message please?” Nemdil asked.

By this point they still had not initiated the turnback, so the controller first instructed, “Could you turn left immediately now onto a heading of zero one zero initially please?”

“We have presently heading zero one zero,” Nemdil replied, confidently incorrect.

“Roger at the moment you’re tracking one zero zero, can you turn left heading zero one zero please?” the controller asked.

“Zero one zero,” First Officer Hantour said aloud, finally beginning the left turn.

Flight 702P crossed the extended runway centerline as it doubled back, so the controller ordered them to turn left even further, to a heading of 260. In the cockpit, Captain Nemdil continued: “If we can’t get it, go around and we try again if we give attention to the fuel.” He meant that if the approach failed, they should immediately try again, fuel permitting.

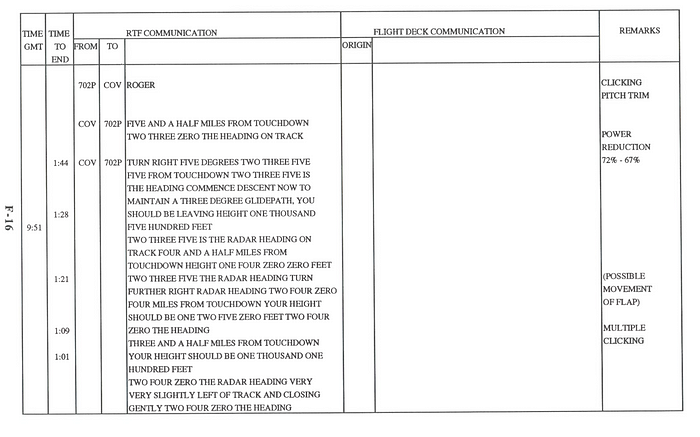

The flight crew still had not confirmed that they wanted an SRA, so the controller offered one unprompted. “Seven zero two papa, approximately twelve miles now to run for surveillance radar approach runway two three,” she said. “That approach terminates at two nautical miles from touchdown, check your minima and missed approach point.”

This transmission was part of the normal SRA procedure, prompting the flight crew to check their company minimum descent altitude or height. In the case of Air Algérie, height above the airfield (QFE) was normally used, so the applicable term would be a minimum descent height (MDH). According to their charts, the MDH for an SRA to runway 23 terminating at 2 miles was 650 feet (916 feet above sea level). However, despite the controller’s reminder, neither crewmember mentioned this number.

In fact, Captain Nemdil appeared not to understand the content of the message at all, because he replied, “Er, roger madam, er, could you give uhh cooperation with uh… SRE [sic] approach?”

“Roger, a surveillance radar approach for runway 23,” the controller reiterated. But she didn’t repeat the “check your minima” call, and the crew never did check their minimums.

“Roger, thank you, because we are not reading the ILS,” Nemdil explained.

“That’s all copied, thank you very much,” the controller said, before launching into the SRA. “You’re ten miles from touchdown now, at your convenience check your wheels, you’re closing the final approach track very gently from the left.”

On board, Captain Nemdil deployed the landing gear, and First Officer Hantour called for flaps 15.

“Distance to touchdown, seven zero two papa?” Nemdil asked.

“Roger, miles from touchdown now nine track miles, niner track miles from touchdown,” the controller reported. “You can expect further descent to maintain a three degree glidepath at four and a half miles from touchdown, I’ll keep you advised.”

Still flying level at 1,500 feet (1,240 ft above the field), First Officer Hantour commented, “We can see the ground.”

“From time to time,” said Nemdil. “It’s not always the case.”

“In patches. It’s in patches,” Hantour agreed.

“Otherwise we come here and try to get below cloud,” said Nemdil.

“Seven zero two papa, turn left now two four zero, the radar heading final approach track,” said the controller.

Nemdil urged Hantour to “Turn turn turn two hundred and forty.”

“Turn further left now two three zero, the heading two three zero,” said the controller.

“Quickly,” said Nemdil. “One hundred and fifty. Put on five degrees more to the left.”

Around this time the controller decided that she would terminate the SRA at 1 mile instead of 2 miles, because the visibility was not looking especially good. However, she elected not to tell the flight crew because they appeared to be having comprehension difficulties.

For a 1-mile or half-mile SRA at Coventry, the minimum descent height was 370 feet above the field level rather than 650 feet, so the type of SRA in use did actually matter. However, given that the crew didn’t understand the transmission in which the controller promised a 2-mile SRA, and given that on previous approaches they had been given half-mile SRAs, the crew might have believed that the MDH was 370 feet all along.

Moments later, the aircraft reached 5 miles from touchdown, at which point the controller began her continuous transmission, providing unbroken instructions, beginning with clearance to commence the final descent to the runway. But for nearly two minutes after the start of this continuous transmission, the pilots said nothing to one another, a yawning silence beneath the steady drone of the air traffic controller. In fact, Captain Nemdil’s instruction to “put on five degrees more to the left” was the last statement by either pilot on the cockpit voice recording.

It was during these two minutes of silence that the final pieces of a deadly puzzle began fitting into place.

After the instruction to descend, First Officer Hantour initiated a descent with a vertical speed of about 1,100 feet per minute, which was very close to the standard 3-degree glidepath. But before long the descent rate increased to 1,450 feet per minute, causing the plane to sink below the glidepath, as though the crew were using the dive-and-drive method. To make matters worse, the landing checklist was never completed — instead, Nemdil simply selected the landing flap setting of 30˚ without comment.

Still descending toward the MDH, the aircraft entered a bank of low clouds at 500 feet. First Officer Hantour reined in the descent rate to 750 feet per minute, but by then their airspeed had increased to 165 knots, which was too fast for this stage of the approach. Was Hantour focusing on stabilizing their airspeed and descent rate? Was he desperately scanning the fog in search of the runway? Was he focusing on the continuous transmission? What about Nemdil — was his gaze focused outside the aircraft too?

There are several avenues of speculation about what happened during those critical moments, with evidence for each. This evidence will be examined shortly. For now it is enough to say that as flight 702P descended into the fog, neither pilot called out their altitude. Neither pilot called out that they were approaching the MDH. Nor did anyone say a word when the aircraft reached the MDH, and continued descending through it.

The air traffic controller had no idea that flight 702P was descending below the glidepath. Her relatively primitive radar presentation could not display an aircraft’s altitude. All she could do was provide the standard reference altitude for each half-mile interval, which she did — and it was the flight crew’s prerogative to ignore them. Unchecked, the descent continued.

At about 09:52 and 30 seconds, descending through a height of approximately 100 feet above the airfield elevation, one of the pilots spotted a flash of something through the fog and let out an exclamation of surprise. And then it was over.

◊◊◊

A split second after the shout, flight 702 slammed headlong into an 86-foot (26-meter) electrical transmission pylon located about 1.1 NM short of the runway. The left wing and engine impacted the middle of three pairs of support arms, shearing off the upper 5 meters of the pylon and snapping the transmission cables, leading to a widespread power outage. In the control tower, electrical power was lost and all the radar displays went blank. The aircraft itself also lost power and both black boxes simultaneously went dead.

For a few harrowing seconds the 737 continued onward, leaving a ruinous trail of debris in its wake. The left engine ceased generating power, and several key portions of the left wing departed the aircraft, including one of the trailing edge flaps. The plane banked sharply to the left, and although the pilots no doubt attempted to recover, it was too late. The left wingtip struck the chimney of one house, followed by the roof gable of a second, sending pieces of aircraft debris and building materials ricocheting across a residential street. Portions of the left aileron were thrown into a domestic garden and the outermost two meters of the wing tore away and came to rest in a tree. Banking beyond 90 degrees, the rest of the airplane flew on for a brief moment, then crashed, completely inverted, into a forest.

Seconds later, backup generators came online at the airport, and the controller called to ask if flight 702P had the runway in sight. Her transmission was met with an unsettling silence. Only then did a column of smoke become visible, billowing ominously above the fog bank, revealing the fate of the aircraft. She immediately activated the crash alarm, sending firefighters scrambling to their vehicles.

At the scene of the disaster, the impact had destroyed most of the forward section of the aircraft, and an intense fire immediately erupted. Bystanders arrived on the scene within seconds and managed to enter the overturned tail section, but found it empty. There were no signs of survivors.

By the time emergency services extinguished the fire, the forward cabin and wings had burned to the ground, leaving only the tail. The bodies of all five crewmembers were found in the wreckage, having perished on impact. Miraculously, no one on the ground was hurt.

However, in a tragic twist, investigators would note that there were two cabin crew seats in the back of the cargo deck that were equipped with seat belts and remained intact during the crash — but the two British livestock handlers weren’t seated in them. The bodies of the handlers were found in the forward cabin, near where witnesses said they had seen cushions laid out on the floor during a stopover. Most likely, the handlers were sitting on the mats in the forward cabin without proper restraints and were killed instantly when the plane struck the ground. However, if they had been seated in the cabin crew seats for landing, with their seat belts fastened, then they very well might have survived, given the lack of disruption to the cabin in this area.

◊◊◊

The investigation into the crash was led by the Air Accidents Investigation Branch of the United Kingdom, which produced an extremely detailed report covering all aspects of the event. It was evident, prima facie, that the aircraft collided with the transmission pylon, leading to a catastrophic loss of lift and thrust on the left side of the plane. The black boxes should have explained why the aircraft was there — but unfortunately, the flight data recorder, a primitive model that recorded data on light sensitive paper, only worked intermittently and was not operating during the accident flight. Only the cockpit voice recording was available.

In order to prove that the aircraft was under control when it struck the pylon, investigators painstakingly matched the damage on the pylon with recovered pieces of the left wing and engine, which collectively demonstrated that the plane was in level flight with a slight left bank and slight nose up attitude at the time of the collision. This was consistent with a plane that was under control. The question then was why the aircraft hit a pylon that was only about 100 feet above the airport elevation, well below the minimum descent height of 370 feet.

The MDH of 370 feet was designed to keep aircraft away from the most prominent obstacle in the area — which was a slightly higher pylon adjacent to the one struck by the plane. By applying a mathematical formula to the height of this obstacle, taking into account its distance from the runway, the CAA had originally arrived at a value of 370 feet as the minimum “obstacle clearance height” for the 1-mile and half-mile SRAs to runway 23. Legally, airlines were free to use any MDH as long as it was equal to or above the OCH.

Until 1991, part of the procedure for an SRA in the UK, on the air traffic control side, was to inform the flight crew of the OCH before beginning the approach. However, two years before the crash, this step was removed in order to reduce the number of radio transmissions during an SRA. This policy was at variance with the recommendations of the International Civil Aviation Organization. The information had been considered redundant because flight crews were expected to have the minimums readily available on their approach chart, and the controller’s “check your minima” call was supposed to prompt the crew to review it. Unfortunately, the crew of flight 702P might not have heard this call and they didn’t respond to it. Investigators agreed that if the crew had been specifically informed of the OCH, then there was some possibility, however small, that they might have remembered to level off before reaching it.

But why did the crew disregard the MDH in the first place? There were several possible ways to approach the question.

It first must be noted that two hours earlier, during the first failed approach to Coventry, the crew correctly followed the 3-degree glidepath and executed a missed approach at the MDH after failing to see the runway. Investigators knew this because a nearby radar site captured numerous approaches to Coventry, with altitude data, even though this was not displayed to the controller. (Incidentally, that’s also how we know the descent rate figures mentioned earlier in this article.) Presumably, then, the crew was aware of the MDH. However, a proper approach briefing, which was likely not performed due to the compressed timeline, would have reduced the risk of accidentally violating it.

The mechanics of how the flight crew would have flown this approach were of greater interest. The accident 737 was very poorly equipped for this type of approach and the pilot workload would have been high. Modern flight director overlays can instruct pilots to pitch up or down to achieve the airspeed and descent rate required for a 3-degree glidepath even in the absence of a ground-based glideslope signal, but 7T-VEE still had the primitive flight director that was installed when the plane was delivered, which lacked this capability.

Furthermore, modern barometric altimeters have adjustable “bugs” that can be set to remind the pilot when the aircraft approaches a desired altitude, such as the MDH. However, 7T-VEE had no barometric altimeter bugs. There were adjustable bugs on the radio altimeter, but this instrument measures only the height of the airplane above the ground directly beneath it, as opposed to a barometric altimeter that can measure the height above the airport. The radar altimeter was thus not very useful for altitude monitoring on approach unless the underlying terrain was perfectly flat, which it seldom is, so it was not Air Algérie policy to use the radar altimeter bugs. The bugs were found in the wreckage set to meaningless values, confirming that they were not used.

Finally, investigators noted that the flight crew did not receive any alert from their ground proximity warning system (GPWS). The Mk. 1 GPWS fitted to 7T-VEE would not sound an alert if the aircraft was descending at a normal rate toward flat terrain in the landing configuration, because such a flight path was indistinguishable from a normal landing. A modern Terrain Awareness and Warning System (TAWS) equipped with a digital airport database may have detected the deviation in this case, but these systems were not yet available in 1994.

Without these tools, the only assurance that the crew would level off at the MDH was the expectation that the monitoring pilot would call out their altitude and advise the flying pilot. Obviously this should happen anyway, but with no flight director, First Officer Hantour would have had to expend the majority of his energy maintaining the 3-degree glidepath by cross-referencing their position and altitude against the reference heights called out by the controller. In this case, the plane’s abnormally high airspeed would also have added to his workload. Only the monitoring pilot’s vigilance would have ensured that the descent was stopped in time. However, Captain Nemdil failed to make the normal altitude callouts, which under these circumstances removed the last surefire barrier against an accident.

The radar data showed that during the accident approach, the crew did not adhere to the 3-degree glidepath or the reference altitudes provided by the controller. Based on the pilots’ comments regarding intermittent ground contact, it was possible that they wanted to perform a dive-and-drive approach in order to increase their time close to the ground, thus maximizing their chances of spotting the runway. However this was not clearly verbalized, nor did the pilots mention the MDH at any point.

A key element of their decision making was presumably the 09:00 weather report that indicated a 600-foot cloud base and an improving trend. But as it turned out, this report was wildly inaccurate. By the time of the accident at about 09:50, witnesses on the ground and in the air observed clouds in the vicinity of the crash site stretching from ground level to 500 feet, with visibility near the pylon estimated at only around 50 meters. The fog was lifting in some areas but not under the approach path.

Investigators found that the 09:00 weather observation was made by a brand new meteorological observer who had just finished his training course one week before the accident. This was his first time calculating the visibility and cloud base in fog. Most likely he applied an incorrect method, and other personnel at the tower did not appreciate that he needed closer supervision.

Tragically, the correct weather was available via the official 08:50 Coventry Airport METAR, which the crew could have consulted in the East Midlands Airport crew briefing room. If they had requested this information then they would have seen that the weather at Coventry was still below minimums and they most likely would not have departed. They also could have verbally requested the weather from the controller before starting the approach, which is normally a standard part of every flight. The fact that the crew omitted to do this was unfortunate. A possible contributing factor was that Coventry Airport lacked an Automated Terminal Information System (ATIS), which continuously broadcasts the latest weather so that pilots can listen at whatever time is most convenient.

As a result of the optimistic report and their failure to follow up, the pilots of flight 702P probably believed that their chances of seeing the runway were high, which was not actually the case. This could have caused them to prematurely focus their attention outside the airplane, leaving no one monitoring their altitude. In a properly disciplined dive-and-drive approach, the monitoring pilot should not take their eyes off the instruments until the aircraft has leveled off at the MDH, but the temptation to look outside is considerable and must be actively resisted. This discipline can be instilled with comprehensive training in crew resource management, or CRM, which helps flight crews distribute shared tasks and communicate with one another about expectations. But at the time of the accident, Air Algérie did not provide its pilots with CRM training.

In the end, the descent below the MDH was probably inadvertent. Captain Nemdil’s statement, “Otherwise we come here and try to get below cloud,” appears to represent wishful thinking and not an intention to violate the MDH.

That having been said, the recovered radar data showed that in the month prior to the accident, 7T-VEE violated the MDH numerous times while under the command of different flight crews. Based on the chart appended to the AAIB report, it appears that some of these flights only narrowly avoided striking the same transmission pylon, possibly by less than 50 feet.* Witnesses who lived in the area confirmed that they had seen 7T-VEE flying abnormally low on multiple occasions. This chilling detail received relatively little attention in the final report but stands out in hindsight as evidence of a major systemic problem at Air Algérie, and suggests that an accident was almost bound to happen.

Investigators theorized that the reason for these low approaches may have been the short runway at Coventry. Boeing guidance available to Air Algérie flight crews stated that crossing the runway threshold just 50 feet too high will add 950 feet to the required landing distance. I don’t know what the calculated landing distance was for an empty 737–200, but on a runway that was only 4,600 feet long, 950 feet is a long way. The AAIB believed that Air Algérie flight crews might have been so concerned about overrunning the runway at Coventry that they habitually flew below the glidepath.

On the other hand, every recorded SRA involving the accident flight crew was performed correctly with reference to the 3-degree glidepath, except for the accident flight. As such there is no particular evidence to suggest that this crew was influenced by the pattern of behavior, except insofar as Air Algérie’s company culture failed to emphasize the risk of flying below the glidepath.

*Note: The radar data is not precise enough to determine exactly how close the aircraft came to the pylon. Assume a large error bar on this number.

Considering the above, it was obvious that the crew of flight 702P was capable of flying the approach correctly. As for why the accident flight ended differently, investigators pointed the finger squarely at fatigue.

After accounting for the delays due to the diversion the flight crew had been on duty for 10 straight hours through the middle of the night, with only 27 hours to adjust to the night shift beforehand. Air Algérie normally restricted night operations to 7 hours and 45 minutes of duty time with four flight sectors, or 5 hours and 30 minutes with five sectors. However, this duty time could be extended indefinitely at the captain’s discretion in the event of unforeseen operational circumstances, such as a diversion. UK law included similar provisions (which were actually even less restrictive). Therefore, no duty time limits were violated on flight 702P because the scheduled portion of the trip sequence contained four sectors and was under 7 hours and 45 minutes.

However, as the flight crew approached 10 hours on duty, the effect of their growing fatigue became readily apparent. They failed to comply with a clearance, they read back multiple instructions incorrectly, and their cockpit conversation was lethargic. Not only did this fatigue likely contribute to their failure to level off at the MDH, it might also have contributed to their failure to brief the approach more thoroughly before the flight, and could have encouraged them to act on incomplete information or ignore circumstances that made the approach unlikely to succeed — what aviators like to call “get-there-itis.” At the end of the day they probably just wanted to get home and sleep.

It has been suggested that some of these mistakes might also have been due to insufficient understanding of English. It’s apparent from their transmissions that the flight crew had only rudimentary English language skills, but language difficulties and fatigue are not mutually exclusive. Understanding a foreign language also gets harder when we’re tired.

◊◊◊

Taken together, the factors mentioned so far point to a high-risk operation, from the long night shift, to the outdated ILS receiver, to the lack of infrastructure at Coventry Airport, to the lack of workload reducing devices on the flight deck. The final mistake, the descent below the MDH, did not occur in a vacuum, but rather within the context of an operating environment that lacked adequate safety margins. The fact that such an environment was allowed to exist raised questions about the quality of oversight in both Algeria and the United Kingdom.

In Algeria, the level of oversight for Air Algérie was essentially zero. The Algerian Department of Civil Aviation did not directly monitor Air Algérie’s operations, instead delegating this task to a group of senior Air Algérie training captains who undertook oversight functions alongside their regular flying and training duties. This is not an effective way to oversee even a tiny puddle jumping airline, let alone the flag carrier of the largest country in North Africa. It was difficult for investigators to make further comments on oversight in Algeria simply because there was none to discuss.

Air Algérie itself was also afflicted by an incomplete and unresponsive organizational structure. The airline had no safety division within its flight operations department and there was no mechanism for flight crews to raise safety concerns with the company, anonymously or otherwise. And when Phoenix Aviation inquired about the outdated ILS receiver, their questions seemingly disappeared into an institutional void. As a result, they missed an opportunity to upgrade the aircraft’s ILS equipment and obviate the need for non-precision approaches. Overall, investigators got the impression that no one at Air Algérie was formally responsible for this type of operational safety.

Once the UK operation began, oversight lapses continued.

Even though the Department of Transport apparently knew that the aircraft was operating without the correct permits, no enforcement action was taken. The reason for this is not stated in the final report.

The issuance of a permit wouldn’t have changed the outcome of the accident, but there were some failed avenues of oversight that very well could have. The CAA was unaware of the operation because the DOT permit process had not been completed. The failure of Air Algérie to submit their Aerodrome Operating Minima to the CAA also left the agency unaware of the operation and unable to enforce the approach ban. Many flights involving 7T-VEE violated the approach ban, and if even one of these had been caught, then the situation likely would have been corrected, and flight 702P would never have attempted to land. Similarly, air traffic controllers observed numerous deviations involving 7T-VEE but none filed reports with the CAA until minutes before the accident.

Investigators also raised a point that I previously discussed in my article on HA-LAJ, another foreign aircraft that crashed in Britain during the same time period. In both reports, the AAIB pointed out that the DOT permitting process was effectively a rubber stamp because Article 33 of the ICAO convention prohibited the UK from denying a foreign airline permission to operate into the country unless the airline or the guarantor of its certificate had been deemed non-compliant with ICAO safety standards. The permitting process didn’t include an assessment of an applicant’s safety standards, so there was no way for a permit to be denied. Both accident reports also pointed out that the United States had recently begun sending teams to audit safety standards in other ICAO member states to provide a basis for permitting discretion, and recommended that the UK begin doing the same.

◊◊◊

In January 1996, the AAIB published its final report, concluding that the probable cause of the crash was the flight crew’s descent below the MDH without visual reference to the runway — a tale almost as old as aviation itself. The flight crew’s impairment by fatigue was also listed as causal to the accident. The report was supplemented by nine safety recommendations addressed to the CAA, the Department of Transport, and Air Algérie, including that Air Algérie implement a safety management system, and that the DOT revise the permit application system for foreign carriers.

Even though the circumstances of the crash were unusual, the accident sequence itself was a textbook case of controlled flight into terrain on a non-precision approach, superficially similar to dozens of other accidents involving transport aircraft. One aspect that stands out, however, is the clear role of fatigue, and the AAIB’s decision to elevate it to a causal factor, which was a relatively new practice at the time. This finding remains relevant because even though duty time limits are stricter today, long overnight shifts are still a fact of life, particularly for cargo pilots. Strategies exist to manage the risks associated with this fatigue, none of which were taken on flight 702P. These can include extra briefings, heightened risk avoidance, additional cross checks, and so on. These tactics must be invoked explicitly and proactively because our instinct when tired is to try to reduce complexity and eliminate “unnecessary” steps. Too often in aviation, the resulting corner cutting only further undermines a margin of error already reduced by the fatigue itself. Evidence of this insidious degradation of discipline could be seen on flight 702P in the flight crew’s failure to properly brief the approach, their failure to ask for updated weather information, and their failure to complete all the applicable checklists — activities that they successfully performed on previous flights.

◊◊◊

After the crash, Phoenix Aviation entered receivership and ceased operations in 1995. Few traces of its existence remain on the internet, but it’s a safe bet that the accident and associated litigation were the primary causes.

The crash also drew further attention to the ongoing veal export controversy, which only continued to escalate over the course of 1995, culminating in a confrontation that became known as the “Battle of Brightlingsea,” in which over 500 protestors were arrested. In 1996, the matter became moot when Europe banned British cattle imports due to the threat of mad cow disease.

In the Coventry neighborhood where the crash took place, the scar remains faintly visible in the forest to this day, a hidden swathe in an out of the way corner of a quiet suburb where the trees are all a little bit shorter. The transmission pylon struck by the airplane was rebuilt and still stands today. The only memorial to the crash is a small plaque near the scene of the disaster. Perplexingly, it reads, “For the heroic crew of five who gave their lives whilst saving ours.”

It’s not uncommon for witnesses to believe that pilots of doomed aircraft steered their crippled planes away from houses at the last moment. Occasionally, it’s even true. But in this case it manifestly was not — although it was miraculous that no houses were badly hit, all evidence suggests that the crew had no control over where their plane was going. Everything happened so fast, it was over in seconds. The fact that no one on the ground was hurt probably had more to do with luck, or if you prefer, fate.

In the end, the crew of flight 702P were neither heroes nor villains. They were victims of a tragedy that could have been prevented; whether by the pilots themselves or by others further removed makes little difference. The circumstances in which they lived and worked made the crash not only possible, but predictable. It was not predicted, or prevented, because no one spoke up, and the mechanisms to do so were not in place. The best way to honor their legacy is for those who work in aviation, whether in a cockpit or in a tower or behind a desk, to ask — simply ask — “Are we doing everything we can to mitigate risk?” If those who were involved in handling 7T-VEE had put more effort into answering this question, this article might never have been written.

_______________________________________________________________

Don’t forget to listen to Controlled Pod Into Terrain, my podcast (with slides!), where I discuss aerospace disasters with my cohosts Ariadne and J! Check out our channel here, and listen to our latest episode on the fiery demise of Swissair flight 111. Alternatively, download audio-only versions via RSS.com, or look us up on Spotify!

_______________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit

Support me on Patreon (Note: I do not earn money from views on Medium!)

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 260 similar articles

(New feature!) Bibliography