Cloudy with a Chance of Corruption: The crash of Bhoja Air flight 213

On the 20th of April 2012, a Pakistani airliner inaugurating a brand new route went down amid a thunderstorm just short of the airport in Islamabad, killing all 127 people on board. It was the second major crash near Islamabad in less than two years, another black mark on Pakistan’s already poor aviation safety record. But in a country where the aviation industry is run by an insular group of politically-connected individuals, there was little expectation that the full story would be told. An official investigation managed to piece together the basic cause, relating a terrifying sequence of events in the 737’s final minutes, as an overconfident and underqualified crew pressed ahead through a dangerous microburst, only to encounter a second, even stronger one moments later. As multiple alarms blared in the cockpit and the first officer pleaded for the captain to go around, Bhoja Air flight 213 plunged downward to its doom, its pilots apparently unaware that they had failed to take even the most basic steps to save their plane. The reason for this shocking display was equally disturbing: in fact, the crew were flying a different airplane than the one for which they had been trained. How this unacceptable discrepancy arose, and why Pakistan’s Civil Aviation Authority failed to notice it, would become the subject of public speculation which cut right to the heart of the nation’s aviation system.

For several decades following independence, Pakistan’s aviation industry was completely controlled by the state under the auspices of flag carrier Pakistan International Airlines. This monopoly ended only in 1993, when reforms were introduced allowing the creation of twelve privately owned airlines to compete with PIA. One of these was Bhoja Air, a scrappy little airline named for a popular medieval king in India, which began operating with a single leased Boeing 737. The airline expanded to several domestic routes, as well as routes between Pakistan and the Gulf States, but within a few years it began to fall into financial insolvency. Bhoja Air racked up so many unpaid landing and parking fees that in 2000 the airline was kicked out of the United Arab Emirates, and shortly thereafter Pakistan’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) moved to shut it down, citing additional unpaid fees for the use of CAA infrastructure. That year, Bhoja Air ceased operations, but its owners never gave up hope, continually ensuring that the CAA renewed their operating certificate every year after that even though they no longer had any planes.

For more than ten years, Bhoja Air remained in this vestigial state, until executives proudly announced in 2011 that the airline was on track to return from the dead. Shortly thereafter, the company acquired three early model Boeing 737–200s which had recently been retired by South Africa’s Comair, including one, originally built in 1985 for British Airways, which was re-registered in Pakistan as AP-BKC.

A few months later, everything was ready for the relaunch. The first Bhoja Air flight since 2000 took off in March 2012, and regular flights continued thereafter. AP-BKC first flew for Bhoja Air on March 29th, and by April 20th, it had accumulated just 69 hours and 41 flights with the company.

It was on that date that AP-BKC was scheduled to inaugurate Bhoja Air’s evening service from Karachi to Islamabad, one of many routes which were being flown for the first time since the airline resumed operations. Designated flight 213, this was a bread and butter route from Pakistan’s largest city to its capital, a regular moneymaker, and there was nothing to suggest that the first flight would be anything but routine.

In command of the very first flight 213 was 58-year-old Captain Noorullah Khan Afridi, a former Air Force pilot with more than 10,000 hours, who had been flying 737s for several years with rival Shaheen Air before switching to the revived Bhoja Air earlier that year. He would be joined by 53-year-old First Officer Javaid Malik, another former Air Force pilot who had worked with Afridi at Shaheen Air since his retirement from the military. Afridi and Malik were said to be close friends — not only did Malik follow Afridi from Shaheen Air to Bhoja Air, they had also been paired together on more than half of the flights they had flown with the new airline so far.

The flight to Islamabad on the evening of April 20th was, as expected, fully booked. Bhoja Air had modified AP-BKC to increase its seating capacity from 100 to 118, and every one of these seats had been filled, although one off duty flight attendant riding as a passenger chose to sit in the cockpit. The addition of several lap children brought the total number of passengers to 121, which in addition to the two pilots and four flight attendants meant that there were 127 people jammed onto the diminutive Boeing 737–200 when it departed Karachi.

By the time flight 213 took off, the pilots were already aware that the weather in Islamabad would be less than favorable. Thunderstorms were gathering across northern Pakistan, and it seemed likely that they would affect not only Islamabad but their first alternate in Lahore as well, which was subject to a “dust thunderstorm” warning until 20:30 that night. By the time the cockpit voice recording began at around 18:08, the weather was the main topic of conversation in the cockpit, and Captain Afridi also informed the passengers that they might experience rain and light turbulence on approach to Islamabad. However, the overall atmosphere was laid back, as the CVR captured Afridi singing a qawwali song called “Let there be peace in my life also,” followed by the traditional Punjabi song “You called us on the canal bridge,” while First Officer Malik jokingly commented on his vocal ability.

With the flight attendants, Captain Afridi was a little more direct than he had been with the passengers: he told them that he anticipated “a lot of bumps,” given the buildups which were appearing on his weather radar. First Officer Malik, noting that Lahore was also affected, suggested that they look up weather information for their second alternate in Peshawar too, just in case. But Captain Afridi blew him off. “No, God will help us,” he declared, apparently certain that he would be able to land.

Ahead of them, their weather radar was painting a squall line: a string of powerful thunderstorms stretching right across the Islamabad metropolitan area. “Oh ho ho, it’s all over, man,” Afridi said.

But there was no suggestion that they fly to Peshawar. Moments later, Islamabad air traffic control called flight 213 and said, “Bhoja 213, approaching position MATIN, pilot’s discretion descent level 200, report leaving 310.”

First Officer Malik acknowledged the transmission and flicked on the fasten seat belt sign while Captain Afridi began to descend toward Islamabad. Afridi seemed increasingly distracted, humming nervously as he kept an eye on the weather. “It seems to be slightly ahead of us,” he said, watching a thunderhead out the window. “This is a series [of storms] okay, it’s known as a squall line.”

One minute later, again observing the weather radar, Malik said, “This will affect us. This one will affect us, won’t it sir?”

“Make a circle and come back?” Afridi mused. He seemed to think that if they could circle around the airport from the other direction, they might avoid the storms. “Give him a call for permission to change the route,” he said to First Officer Malik.

After clearing flight 213 to descend to 9,500 feet, the controller asked the crew, “And uh, Bhoja, as-salamu alaikum, if able can you give us weather brief on Islamabad?”

“Yeah,” Afridi replied, “it is a squall line through out from the — almost, it is going from 19 miles from the western side, that is the, uh, my heading is 300 degrees and there is no gap to come inside, so is it possible that I go and come from the west?”

Flight 213 was approaching from the southeast, where the storms were strongest. Afridi hoped the controller’s radar might show a gap to the west, where they couldn’t see.

“Bhoja 213, radar is not observing any gap towards west, however I am observing some kind of gap between radial 160 [degrees] to radial 220 [degrees],” the controller said.

According to the controller, there was an area free of storms to the south of the airport, but only across a relatively narrow 60-degree range. “It is right, you go through from 160 to 220 up to here,” First Officer Malik said.

“Ah, that is a very small one,” Afridi told the controller, “[but] let me try that one.”

Afridi was right that the gap was very small. Proper operating procedures held that they must stay five nautical miles away from thunderstorms at all times, and the gap was less than five nautical miles wide. But the crew had decided to run it anyway.

For the next several minutes, the pilots and controller negotiated the route they would use to penetrate the squall line, eventually settling on a right turn to the north through the gap followed by a hard left turn to line up for an instrument landing system (ILS) approach to runway 30 from the southeast. Thankful for the assistance, Captain Afridi, who was apparently on a first name basis with the Islamabad approach controller, said, “Mukhtar, very nice, it was very nice whatever you told me.” Since flight 213 was the only plane approaching Islamabad at that time, the pair struck up a casual conversation, which continued for about 30 seconds before the subject again returned to the weather.

“After another about 30 miles you might intercept a little bit of precipitation till intercepting the localizer,” the controller said.

“Very nice mashallah,” Captain Afridi said. “I got used to it while I was abroad, such beautiful weather, very nice.” He was probably referring to the weather in the Gulf, where he often flew when he worked for Shaheen Air.

Turning to his First Officer, Afridi said, “It has kept us under pressure and we were afraid for nothing.” He then glanced back to the off-duty flight attendant riding in the jump seat and joked, “It’s because of your mother.”

The off-duty crewman’s mother was in fact aboard the airplane. He had also brought cigarettes, and appeared to be lighting one up in the cockpit. “Ammar is smoking a cigarette, yes he is,” Afridi said, eliciting laughter. Outside the cockpit, lightning flashed in the distance.

Descending toward 5,500 feet, the pilots began configuring their airplane, setting up their instruments to intercept the ILS. The lightning was getting closer now, but they pressed on. The controller reported variable winds at 20 knots and light rain over the runway, but Afridi merely thanked him and continued. Their weather radar showed that the center of the squall line was 15 miles away from them, while they were 14 miles from Islamabad airport, placing the worst of the weather very close to the runway. With any luck they could get in beneath it before its full force struck the airport, but it would be a tight squeeze.

“Uh, it is exactly overhead,” said First Officer Malik. “So… we are likely to get very close to it.”

Rain began to dot their windscreen. “It has already hit us,” said Captain Afridi.

Conditions were worsening rapidly. “When we turn this side then it will get slightly intense,” said Malik.

“Haha, now it’s becoming dark,” said Afridi. The storm was closing in around them — and the gap they had planned to follow was fast disappearing.

Descending through 2,500 feet above the ground, now passing in and out of the edge of the squall line, the pilots continued to configure the plane. Captain Afridi accidentally disconnected the autopilot, triggering an alarm, but he immediately put it back on, joking, “Oops, what have I done?”

But his attention still primarily lay with the weather. To his disappointment, the squall line had moved across the airport and was now directly in their path. “It’s exactly on top,” he said to the controller, worry evident in his voice.

Flight 213 began its final turn to line up with the runway, and First Officer Malik extended the flaps to position 1 and deployed the landing gear. As he did so, the plane encountered a performance-increasing headwind, and their airspeed quickly began to climb, causing the autothrottle to struggle to maintain the speed selected by the crew.

“Speed 220,” First Officer Malik warned. The maximum speed with the flaps extended to position 1 was 190 knots, so they were flying much too fast.

“What?” Afridi exclaimed, seemingly confused as to why the autothrottle would allow that to happen. He had no idea that the reason for the sudden acceleration lay not with the plane’s automation, but with the wind outside the aircraft. Neither pilot knew it yet, but they were approaching one of the most dangerous weather phenomena known to aviation: a microburst.

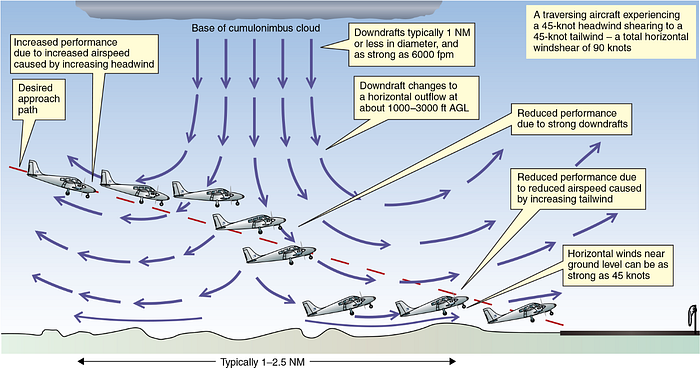

A microburst occurs when a cold air mass at the top of a thunderstorm becomes too heavy for the storm’s convective structure to support, causing it to descend rapidly until it strikes the ground. This air then spreads out in all directions, creating a 360-degree zone of powerful straight-line winds surrounding a central downdraft. This creates a rapid change in wind direction over a small geographical area, a phenomenon known as wind shear. An aircraft encountering microburst wind shear at a low altitude will first experience a strong headwind which increases performance, often causing an unsuspecting pilot to decrease engine power to prevent the plane from climbing. However, the headwind will quickly diminish, only to be replaced by a downdraft which forces the plane toward the ground. A pilot or autopilot will then instinctively pitch the nose up to compensate and increase lift to prevent the plane from descending. And then, finally, the plane will come out the other side of the microburst, experiencing a tailwind which decreases performance severely. If the pilot has already reduced engine power to counter the headwind and pitched up to counter the downdraft, then upon encountering the tailwind, the plane may not have the performance needed to prevent a catastrophic loss of airspeed and lift followed by ground impact.

Unaware that they were flying toward a microburst, Afridi and Malik allowed the autothrottle to pull engine power back until the speed returned to the selected value of 170 knots. Simultaneously, the autopilot intercepted the localizer and glide slope, aligning with the runway and beginning a controlled three-degree descent toward the threshold.

Then, less than two minutes after first encountering the headwind, flight 213 flew into the central downdraft of the microburst, and vertical winds began to build toward -2,400 feet per minute. The autopilot pitched up to prevent the plane from descending below the glide slope to the runway. As the nose pitched up, drag increased, and their speed began to drop. Heavy rain pounded the aircraft with a steady roar.

Then, the microburst’s central downdraft hit with its full force, sending the plane plummeting nearly 1,000 feet in a matter of seconds. Warnings blared in the cockpit: “WIND SHEAR! WIND SHEAR!”

“No! No!” Captain Afridi shouted over the unholy din. But he seemed paralyzed, confused, unsure what to do as his plane dropped toward the ground.

“Go around! Go around!” screamed First Officer Malik.

But the downdraft dissipated just in time. Flight 213 leveled off at a height of 900 feet above the ground, its speed dangerously low due to the building tailwind, but nevertheless still flying. Captain Afridi pitched the nose down to increase speed, but now they had deviated to the left of the localizer, losing their alignment with the runway. The autopilot, lacking the authority to turn sharply enough to return to the localizer, abruptly disconnected with a loud cavalry charge alarm. They were below the glide slope, left of course, surrounded by rain and howling winds, but still the crew pushed on, clearly terrified but unsure how to get out of danger.

The approach controller, not realizing that flight 213 was in a state of emergency, now called the crew to make the handoff to the tower. “Deal with the channel!” said Afridi, focusing all his energy on controlling the plane.

Suddenly, the ground proximity warning system sounded: “WHOOP WHOOP,” it said, before cutting off. Nobody reacted.

Still flying too low, flight 213’s airspeed began to increase again, and the autothrottle again reduced power to maintain the selected speed of 170 knots. The Captain, gripped by fear, and the First Officer, distracted by the control handover, did not recognize that they were encountering the outer headwind from a second microburst — and this one was even stronger than the first.

Over the next 15 seconds, the headwind rapidly dissipated, replaced by another downdraft which built up toward -3,000 feet per minute. With the engines at a low power setting, the plane did not have enough energy to overcome it, and they began to descend. The ground proximity warning system came to life a second time, calling out, “WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP! WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP!”

In response to the warnings, Captain Afridi pulled the nose up, but he failed to increase power. He did not seem to realize that the autothrottle, which was still trying to maintain 170 knots — a speed too low to safely penetrate a microburst — was actively working against him.

Suddenly, the downdraft completely vanished in the space of just four seconds. With the plane already in a nose high attitude due to Afridi’s inputs, the disappearance of the downdraft had a catastrophic effect on its angle of attack — the angle of the wings relative to the oncoming airflow. When a plane flies through a downdraft, the net direction of the oncoming airflow over the wings angles downward, allowing the plane to fly in a nose-high position while maintaining a reasonable angle of attack (see above diagram). However, if this downdraft then goes away, the vector of the oncoming airflow will swing back toward level again, causing the angle of attack to rapidly increase even if the plane’s pitch angle doesn’t change. If the resulting angle of attack is too great, the plane could stall. This is what happened on flight 213 — flying slowly with a high pitch angle, the 737 emerged from the downdraft and almost immediately approached the stall regime, triggering the stick shaker stall warning.

Realizing that the plane was about to stall, Captain Afridi pitched down sharply, reaching 12 degrees nose down in an attempt to reduce their angle of attack. The plane began to accelerate as it hurtled downward, but the autothrottle again reduced thrust to 40% in an attempt to prevent their speed from going above the selected value of 170 knots. Afridi should have disconnected it long ago, but he barely seemed to know what was going on.

Almost as soon as he pitched down to avoid the stall, the ground proximity warning system activated a third time. “WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP!” it screeched. “WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP! WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP!”

The tower called flight 213 with a landing clearance, but there was no reply.

“WIND SHEAR!” another alarm blared. “WIND SHEAR! WIND SHEAR!”

In a desperate attempt to avoid the ground, Captain Afridi pulled the nose back up a second time, only for the stick shaker stall warning to come on again with a rapid-fire clacking sound.

“Stall warning, let’s get out!” Malik exclaimed.

“WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP!” the GPWS called out, over and over and over again.

Captain Afridi pitched down again to avoid the stall, but they were running out of altitude. If he kept descending, they would hit the ground, but if he tried to pull out, they would stall. They were critically low on kinetic energy and desperately needed to increase thrust, but still the thrust levers sat right where the autothrottle had put them, at 40% power.

“WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP! WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP!”

“Go around, go around sir, go around!” First Officer Malik screamed.

“WHOOP WHOOP, PULL UP! WHOOP WHOOP, PULL — ”

And then, with a horrific crunch, the aircraft struck the ground.

Flight 213 touched down on its main landing gear in a field, continued forward momentarily, then plowed headlong into a 5-meter-high earthen embankment. The massive impact instantly tore the plane apart, catapulting shards of burning wreckage up and over the terrace and down a street in the village of Hussain Abad. Within seconds, the shattered debris skidded to a halt, strewn for several hundred meters across the edge of the town. By the time silence finally fell over the grisly scene, all 127 passengers and crew lay dead beneath the rain.

◊◊◊

When rescuers arrived on the scene, they found that little remained of the 737, save for its tail and a twisted section of fuselage which had come to rest on the street. Of those on board, none had survived, and few bodies were found intact. The only small comfort was that despite crashing into a populated area, no one on the ground was hurt.

Unfortunately, for the people of Pakistan the scene was not unfamiliar. Less than two years earlier, Airblue flight 202 had crashed into a hill while on approach to the same airport, killing all 152 people on board. The investigation into that crash had barely answered even the most basic questions about why it happened, providing only a sequence of events without examining the underlying circumstances. Among the public, it was widely believed that Airblue’s politically connected owners had leveraged their influence in Pakistan’s CAA to avoid deeper scrutiny, although direct evidence of this is scant. Either way, however, Pakistan diverged from international standards in that the CAA was responsible for investigating aircraft accidents while also being charged with creating and enforcing safety regulations, inspecting airplanes, and certifying airlines. This conflict of interest would come to color the investigation into the Bhoja Air crash as well.

As the investigation got underway, an analysis of the cockpit voice recording and flight recorder data painted a picture of what happened, if not why. As flight 213 entered a thunderstorm on approach to Islamabad, it encountered two successive microbursts, leading to a loss of speed, a loss of altitude, and two near-stalls before it finally impacted terrain. Captain Afridi found himself caught between a stall and the ground, able to avoid one or the other, but not both. And the data revealed his mistake: not once during either microburst encounter did he ever increase engine power. Simulations would later show that the plane could have climbed away from the danger at any point during its final moments if full power had been applied, but it never was. This shocking lack of action directly contradicted both the wind shear recovery procedure and the terrain escape procedure, one or both of which should have been initiated, and both of which called for the thrust levers to be advanced to takeoff/go-around power or higher.

In fact, the landing was a total disaster from the beginning, as the pilots broke almost all the rules of a stabilized approach. They knowingly flew less than five miles from an active thunderstorm, and continued to descend even after entering a lightning-producing cumulonimbus cloud, something every pilot is trained never to do. They exceeded the maximum speed with flaps in position 1, and they failed to extend the flaps to the proper position for landing, even after the point at which they were supposed to be fully configured. They failed to react in any way to the wind shear warnings, fell way below the glide slope, drifted left of the localizer, and received multiple terrain alarms. The plane was screaming at them to abandon the approach and go around, but Captain Afridi never did so, even after First Officer Malik suggested it. And when all of these mistakes put flight 213 into a dire emergency close to the ground, Afridi failed to do the one thing which was required of him: to fly the airplane.

Several factors may have led the crew to continue an approach which was clearly unsafe. Foremost among them was the fact that this was Bhoja Air’s inaugural evening flight on the Karachi-Islamabad route, and within the company it would have been seen as inauspicious for the flight to land anywhere other than at its scheduled destination. This pressure could have increased the crew’s willingness to take risks, such as continuing the approach even after entering a known thunderstorm. But investigators also noted a generally lax attitude within the cockpit, as Afridi and Malik exchanged jokes, sang songs, and allowed the jump seat passenger to light a cigarette. In some sense, the two pilots — who had been friends for several years — might have been too comfortable with each other, trusting one another so completely that they felt little need to adhere strictly to standard operating procedures, many of which are designed to allow opportunities to catch errors by other crewmembers. Unfortunately, this trust may have doomed everyone on board. Unwilling to believe that his respected captain could have lost control of the situation, First Officer Malik never intervened to save the plane, even though no particular skill would have been required to do so.

All of that having been said, pitching up and accelerating in response to a wind shear warning or ground proximity warning should have been almost instinctive for any properly trained commercial pilot. That led the investigators to examine the training which the pilots received before flying for Bhoja Air. It was here where they uncovered their most surprising revelations: that the pilots of flight 213 had been trained to fly the wrong type of plane.

Despite Boeing’s efforts to make them as similar as possible, not every Boeing 737 is the same, and large variations can exist even within the same generation of this ubiquitous model. It was therefore significant that the plane which crashed in Islamabad was not a base model Boeing 737–200, but a 737–200 Advanced, which came with a fully-automated cockpit more similar to a second generation 737–300 than to the original 737–200. Among multiple differences between the base model and the -200 Advanced was that the latter had an autothrottle, which allows automatic control of engine thrust, while the former did not.

But when investigators looked over the training program at Bhoja Air, they discovered that there was absolutely no indication anywhere in the program that the plane was anything other than a base model 737–200. The training program made no mention of any of the automated flight deck elements, including the autothrottle, and neither pilot was trained to use it.

Considering this information, it could be speculated that Captain Afridi failed to advance the thrust levers during the critical emergency because he overestimated the autothrottle’s capability to react in extreme situations. In fact, the autothrottle on the 737–200 Advanced, which was designed around 1970, is not very sophisticated: it will simply move the thrust levers as necessary to maintain the speed selected by the pilots, much like the cruise control in your car, and it has very little functionality otherwise. But the pilots of flight 213, who as far as investigators could tell had never flown a plane with an autothrottle until they started at Bhoja Air about a month before the crash, had not been told this. And if they wanted to find out the extent of the autothrottle’s capabilities, they could not have done so, because the manual aboard the plane also belonged to a base model 737–200.

As such, it was entirely possible that Captain Afridi believed the autothrottle would automatically increase thrust when he pitched up in response to the ground proximity warning. Alternatively, he might not have realized that it did not disengage at the same time as the autopilot, and thus assumed thrust levels were still at some higher setting that he remembered seeing earlier in the flight. Either way, a lack of understanding of the system surely played a role in his failure to disconnect it and increase thrust manually.

But in terms of the pilots’ failure to react properly to the warnings, their lack of training about the autothrottle was only half the problem. Investigators also noted that neither pilot had received training on responses to GPWS warnings or wind shear warnings while undergoing introductory training with Bhoja Air. During the training period, which took place in South Africa, the procedures for recovery from these situations were not covered, nor were Pakistani pilots required to undergo such training in the first place. Consequently, the pilots had not sufficiently internalized the sequence of actions which they would have to perform — that is, disconnect the autothrottle; advance the thrust levers to takeoff/go around power or higher; and pitch up to (but not beyond) the stick shaker angle of attack. If these actions are not rendered instinctive, a pilot’s panic response might instead be to freeze, which is on some level what happened to the crew of flight 213.

The investigation also considered, but ruled out, a number of other factors. One of these was that the pilots had inadequate knowledge of the weather, a theory which was eliminated due to numerous comments captured on the cockpit voice recorder in which the pilots discussed the presence and nature of the thunderstorms. Although the pilots failed to tune in to the official weather report from Islamabad’s Automated Terminal Information Service (ATIS), they were clearly aware of the severity of the weather and should have known not to fly through it. Similarly, any negligence on the part of the controller was ruled out, since the decision to penetrate the weather lay wholly with the pilot, and the controller did not have the authority to turn them away as long as the airport was open.

All of these revelations were included in an official report, published by Pakistan’s CAA in January 2015, nearly three years after the accident. The cause was determined to be the captain’s failure to increase thrust after encountering a microburst, and the first officer’s failure to take control when he did not do so. But the report was marred by an internal structure which deviated from international standards; imprecise and confusing phraseology; poor grammar; and other obvious flaws. Furthermore, it didn’t answer some of the most troubling questions about the crash of flight 213 — in particular those involving the CAA and its oversight of Bhoja Air, a topic which was barely addressed in the report.

By the time of the report’s publication, Bhoja Air had already ceased to exist. At the time of the accident it had only three aircraft, which was the minimum allowed under Pakistani law. Although the CAA granted Bhoja Air a grace period in which to replace the crashed plane, another of its 737s soon developed a mechanical problem and had to be grounded. With only one operational airplane remaining, the airline was deemed no longer compliant with regulations and had its license suspended by the CAA. The airline flew passengers for the last time on May 29th, 2012 and was liquidated soon after.

However, a number of discrepancies called into question the CAA’s decision to allow Bhoja Air to begin operations in the first place. Foremost among them was the question of why the CAA did not discover that the airline was training its pilots to fly the wrong type of 737. In its accident report, the CAA claimed that it did not know the plane was actually a 737–200 Advanced, as opposed to the base model, because Bhoja Air never told them. No deeper explanation was attempted. However, news articles have rightly pointed out an inherent contradiction: if the CAA had granted the accident airplane a certificate of airworthiness, something which should require a thorough inspection, then how could they have failed to notice that it was not the model Bhoja Air claimed it to be?

One possible explanation, gleaned from the pages of the official report, was that the CAA inspector assigned to Bhoja Air had no experience with the 737–200, and did not monitor the airline’s pilot training program, both of which were major bureaucratic failures in and of themselves. However, numerous news articles have also alleged a far less innocent explanation: that Bhoja Air’s clearance to fly was rubber-stamped without any kind of inspection as a political favor between Bhoja Air executives and high-level CAA officials. No direct evidence of such a deal has emerged, but a judicial report, seen by multiple Pakistani news agencies in 2018, did allege that Bhoja Air had pressed the CAA to grant it permission to begin operations despite the fact that the company was “financially not in the soundest health and seemed not to possess requisite infrastructure.” Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper added that according to the report, the accident airplane was operating without a certificate of airworthiness that would allow it to carry passengers, and was doing so with the full knowledge of the CAA. These allegations appear to substantiate the theory that the CAA approval of Bhoja Air’s revival was not exactly an above-the-table affair.

Unfortunately, as so often happens with cases of corruption in Pakistan, the full story of Bhoja Air’s brief and deadly return to service may never be known. The aforementioned judicial report did result in nine former Bhoja Air executives and CAA employees being charged with serious crimes, but it did not appear that senior officials were among them, and four years later it remains unclear whether any of the nine were convicted. In the meantime, two more major air disasters have occurred in Pakistan since the crash of flight 213, and the country remains one of the most dangerous places to fly. Pakistan’s recent move to transfer responsibility for accident investigation from the CAA to an independent agency is a step in the right direction, but there is still a long way to go.

In the end, the crash of Bhoja Air flight 213 does not provide much of a cautionary tale for pilots; in fact, any properly trained pilot should be able to easily avoid a similar fate. The crash was more the result of a systemic disregard for safety and for the rule of law at a high level within Pakistan’s aviation industry. The pilots made serious mistakes, but those mistakes were the product of the environment in which they lived and worked. And when that operational environment is as troubled as it is in Pakistan, reform needs to come from the top — the safety of Pakistani air travelers depends on it.

_________________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit!

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 220 similar articles.

You can also support me on Patreon.