Cogs in the Machine: The crash of Colgan Air flight 3407 and its legacy

On the 12th of February 2009, a Bombardier Q400 turboprop flying on behalf of Continental Connection lost control on approach and plunged into a neighborhood near Buffalo, New York, killing all 49 people on board and one on the ground. The crash immediately galvanized unprecedented public attention, triggering a popular movement for aviation safety that grew with each new revelation uncovered by the National Transportation Safety Board. At the same time, within the aviation community the crash came to be viewed as a product of many of the most serious and intractable problems affecting the industry, from pilot working conditions and pay to training and professionalism, especially at the so-called regional airlines, which operated on behalf of, but without oversight from, the handful of carriers widely known to the general public.

Propelled in part by outrage over conditions at the regional airlines, the United States Congress responded to the crash by passing tough new safety rules that altered the working landscape for American pilots. Undoubtedly the most widely known component of the overhaul was the requirement that all airline first officers acquire an Air Transport Pilot certificate, popularly known as the “1,500-hour rule,” which is now the subject of increasingly public debate. Did the rule make flying safer? Or is America’s unprecedented safety record, with only two passenger fatalities on US airlines since the disaster in Buffalo, unrelated to what some considered kneejerk legislation? And perhaps most of all, does the unimaginable success of the current system render any calls for regression inappropriate, regardless of whether causation can be established? Those hoping for a definitive answer won’t find one here, but they will find a compelling story of transformation, from a few critical seconds of chaos in a cockpit over Buffalo, to the complex and still-unfolding legacy they left behind.

◊◊◊

In 1965, WWII veteran and pilot Charles Colgan founded a flight school and general aviation support service at Manassas Airport in Virginia, which he named Colgan Airways Corporation, after himself. By 1970, the business had expanded to include small charter and air cargo operations, and by 1980 the deregulation of the airline industry opened the door for the company, now calling itself Colgan Air, to begin operating scheduled passenger flights as well. Colgan was among the initial wave of companies that responded to deregulation by taking over poorly trafficked routes to destinations off the main lines, a type of service that was being abandoned by major carriers due to the withdrawal of most government subsidies. These companies, now known as “regional airlines,” entered into contracts with major carriers like Pan Am, United, and American Airlines in order to maintain these routes using smaller aircraft more appropriate to the level of demand, while capitalizing on brand recognition by doing business under the major carrier’s name.

Between 1986 and 2009, Colgan Air held contracts — known as feeder agreements — with several airlines, including New York Air, United Airlines, and US Airways, but the one carrier to which it always returned was Continental Airlines, a partnership that allowed the company to operate under the brand name Continental Connection. By 2007, Colgan Air held agreements with several carriers simultaneously, including Continental, when it was strategically acquired by the Pinnacle Airlines Corporation, the owner of rival Pinnacle Airlines, which mostly operated under the Northwest Airlink brand.

Following the acquisition by Pinnacle Airlines, a decision was made to greatly expand Colgan Air’s operations. At that time, the company operated a fleet consisting mainly of 35-passenger Saab 340 commuter planes, but beginning in January 2008 it broke new ground by acquiring no less than 15 Bombardier DHC-8 Q400 twin turboprop regional airliners, each of which could carry up to 74 passengers. Even more were scheduled to be added in the near future, a huge fleet expansion that required Colgan Air to hire approximately 200 new pilots in less than a year, while establishing an entirely new operating base at Newark International Airport in New Jersey. Many of these pilots had to be trained at third party facilities because Colgan Air didn’t receive approval for its own Q400 training program until July 2008, six months after Q400 operations began.

Among the pilots assigned to the new Q400 fleet was 47-year-old Captain Marvin Renslow, who had been flying Saab 340s at Colgan for several years before completing training on the much larger Bombardier in December 2008. Colgan Air’s seniority structure allowed him to transfer directly from the left seat of the Saab to the left seat of the Q400, without spending any time as a Q400 First Officer, and by the second week of February 2009, he had only 111 hours on the type, out of 3,379 hours total.

Meanwhile, one of the numerous new pilots hired directly to fly the Q400 was 24-year-old First Officer Rebecca Shaw, who was part of the initial hiring wave in January 2008 and had since accumulated 774 hours in the Q400, out of 2,244 total hours. Prior to her employment with Colgan Air, she had worked as a flight instructor on various single-engine airplanes in Arizona, and this was her first job with an airline.

On February 12th, 2009, Captain Renslow and First Officer Shaw were assigned together to fly a series of Q400 flights in and out of Newark, which is where the story of the coming disaster begins in earnest.

◊◊◊

Although Colgan Air, like any airline, preferred that its Newark-based pilots live in Newark, the majority did not, and that made life more complicated for both of this story’s antiheroes. Marvin Renslow lived with his wife and kids near Tampa, Florida, about 1,600 km to the south, necessitating a long commute. But Rebecca Shaw was even less strategically located: in order to save money, she and her husband of two years had recently moved from Virginia to her parents’ house in Seattle, Washington, over 3,800 km from Newark and on the complete opposite side of the country.

Although Colgan Air asked its commuting pilots to arrive at their base the day before the first scheduled flight of a given trip sequence, following this advice tended to decrease time spent with loved ones and was commonly ignored. For Captain Renslow, who was already in Newark prior to the February 12th assignment, this was not presently important. But for First Officer Shaw, the 12th was the first day of a new rotation, and she did not leave Seattle until the evening of the 11th, when she boarded a FedEx cargo plane as a non-revenue passenger on a flight to that company’s distribution hub in Memphis, Tennessee. Another off-duty pilot riding on that flight would later state that he saw Shaw sleep for about 90 minutes during the cross-country flight, which arrived sometime after 2:00 a.m. Eastern time. Shaw then boarded another FedEx cargo flight to Newark at 4:18 and slept throughout the flight, arriving at 6:23. The FedEx captain asked her if she had a place to stay, to which she allegedly replied that one of the couches in the Colgan Air crew room “had her name on it.”

As it turned out, Captain Renslow was already in the crew room, sleeping on a couch of his own. Although sleeping in the crew room was technically prohibited — and probably not very comfortable, because the lights were on and people constantly came in and out — nobody attempted to stop him. He was most likely asleep on a couch for two distinct periods in the early hours of the 12th, with a brief interruption around 3:00 a.m. when Colgan Air’s crew scheduling website recorded him logging in. First Officer Shaw joined him sometime around 7:00, and was observed asleep at various points throughout the morning.

Both pilots were originally scheduled to report for duty at 13:30, but their first round trip to Rochester, New York and back was cancelled due to high winds, and their next scheduled flight was not until 19:10 that evening. Both pilots therefore spent most of the day in the crew room conducting various activities, including but not limited to resting, eating, chatting with other pilots, and watching TV.

At the appointed time, now well into the evening and after nightfall, the pilots reported to the gate and prepared their Q400 to operate Colgan Air/Continental Connection flight 3407 to Buffalo, New York. Two flight attendants and 45 passengers also boarded, totaling 49 occupants, including an off-duty pilot riding in the cabin. But even after everyone was aboard, the weather delays continued — the plane did not push back from the gate until 19:45, 35 minutes after it was supposed to depart, and the flight subsequently sat for 45 minutes on the apron before finally receiving permission to taxi at 20:30, by which time there were still 20 planes ahead of them in line for takeoff.

During the lengthy delays, the cockpit voice recorder captured the pilots discussing a variety of topics, many of which provided fascinating insights into their lives and stressors. First Officer Shaw remarked that her preferred operating base would be “anywhere but Newark,” given its distance from Seattle; recounted her experiences flight instructing in Arizona; and mentioned the fact that they wouldn’t be paid for their wasted time following the cancellation of the flight to Rochester. At one point a flight attendant called on the interphone and mentioned in passing that the passengers were “not very happy,” but there was nothing the pilots could do about that, and they went back to chatting. Captain Renslow mentioned that since transitioning to the Q400, he was “getting screwed on the schedules,” and stated that he made $60,000 the previous year. First Officer Shaw was not so financially lucky: “I made gross $15,800,” she said. Captain Renslow mentioned something about “FO welfare,” to which Shaw replied, “I’m just lucky I have a husband that’s working.”

Sometime during this period, First Officer Shaw began displaying symptoms of a head cold, only adding to her misery. The cockpit voice recorder captured the sound of frequent sniffling. As they inched forward in line, she commented, “Oh, I’m ready to be in the hotel room.”

“I feel bad for you,” said Captain Renslow.

“Well, this is one of those times that if I felt like this when I was at home there’s no way I would have come all the way out here. But now that I’m out here…”

“…You might as well,” Renslow finished for her.

“I mean, if I call in sick now, I’ve got to put myself in a hotel until I feel better,” she said. “You know, we’ll see how it feels flying. If the pressure’s just too much I could always call in tomorrow, at least I’m in a hotel on the company’s buck, but we’ll see. I’m pretty tough.”

According to Colgan Air policy, if she called in sick before the start of the trip sequence, she would have to pay for her own lodgings until she felt well enough to work again, potentially incurring significant expense. On the other hand, if she completed the flight to Buffalo and called in sick afterward, Colgan Air would pay, and given her salary this was clearly the preferable option.

In the meantime, Captain Renslow suggested that she treat her symptoms with some Airborne, vitamin C, and a glass of orange juice.

As the delay continued, so did the pilots’ lengthy and animated discussion, touching on Captain Renslow’s prior work history, real estate, and the merits of various airplanes. Shaw also mentioned that she was expecting to receive a $5-an-hour raise, but would not get it until the next pay period, shorting her $200. “Two hundred bucks to an FO is a lot money,” she pointed out. Minutes later, she ranted some more: “Gosh, I’m so freaking mad,” she said. “I feel like Colgan walks all over me. This company treats me like crap so much.” She went on to explain that she had been randomly assigned her vacation at an inconvenient time of year and that the responsible manager was ignoring her calls and emails in an effort to avoid addressing the issue until the deadline to change it had passed.

Finally, at 21:16 — more than two hours after their original scheduled departure time — it appeared that takeoff clearance was imminent, and the pilots broke off the conversation to complete the taxi checklist, then the before takeoff checklist. At 21:18 they were cleared for takeoff, and within 30 seconds they were in the air, over two hours behind schedule. Respecting the sterile cockpit rule, which prohibits non-pertinent conversations below 10,000 feet, they initially limited their discussion to the operation of the aircraft, but once they were above that height, they simply picked back up where they left off, talking about vacation schedules.

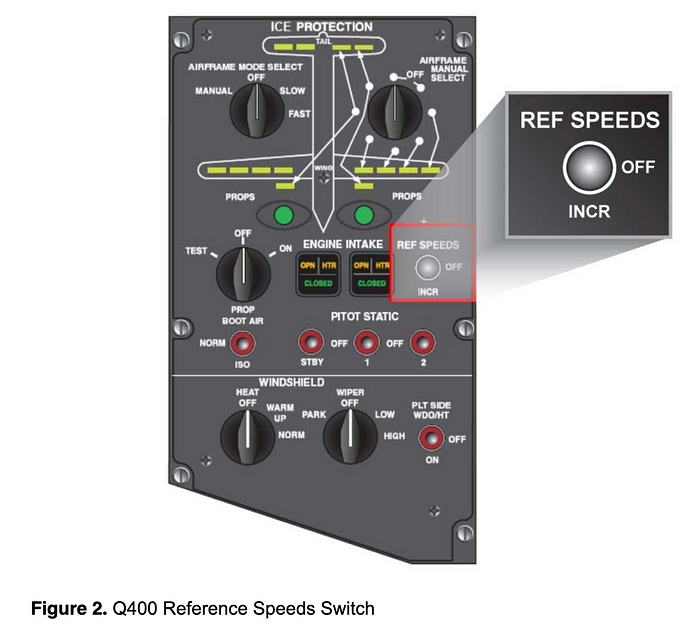

As they climbed, Captain Renslow was aware that various parts of the route to Buffalo would be in clouds where ice accumulation was forecast. In order to reduce the danger of any ice buildup, the crew activated all the de-icing equipment, including sensor heaters, wing de-icing boots, and other systems. Additionally, per the Q400 flight manual, Captain Renslow is thought to have made one other minor but hugely consequential adjustment: he flipped the “reference speed switch” from “OFF” to “INCR.”

The background behind the existence of this unusual switch is worth examining.

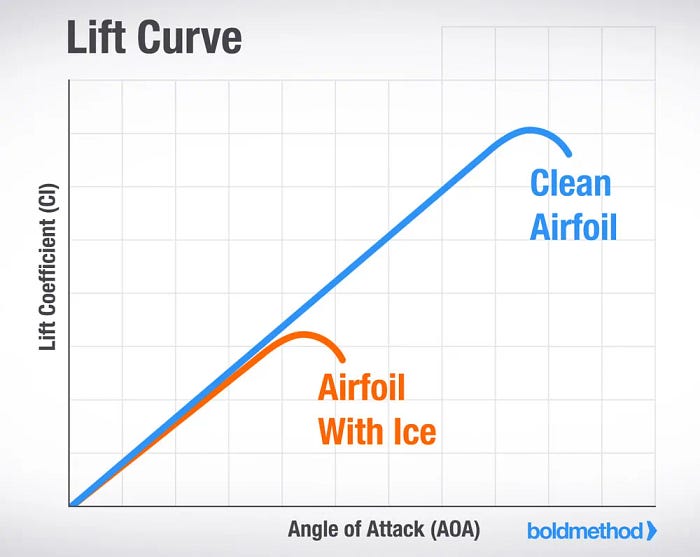

When flying in icing conditions, the accretion of ice can have a negative effect on performance by increasing drag and interrupting the smooth airflow over the wings, which raises the risk of a stall. In normal flight, maintaining lift requires a balance between airspeed and angle of attack, or the angle of the wings into the airstream; therefore, as speed decreases, angle of attack (or AOA) must increase, but only as far as the critical AOA, at which point air ceases to flow smoothly over the wings and a stall occurs. Normally, an airplane will stall at a predictable AOA for any given configuration and altitude, but if there is ice on the wings, this added roughness can cause the flow to break up earlier, resulting in a stall at a lower AOA, and thus also at a higher airspeed. Because aircraft stall warnings are based on the expected stall AOA only, the presence of ice can cause a stall to occur before the stall warning goes off, a very dangerous condition that I discussed in detail in my previous article on Comair flight 3272.

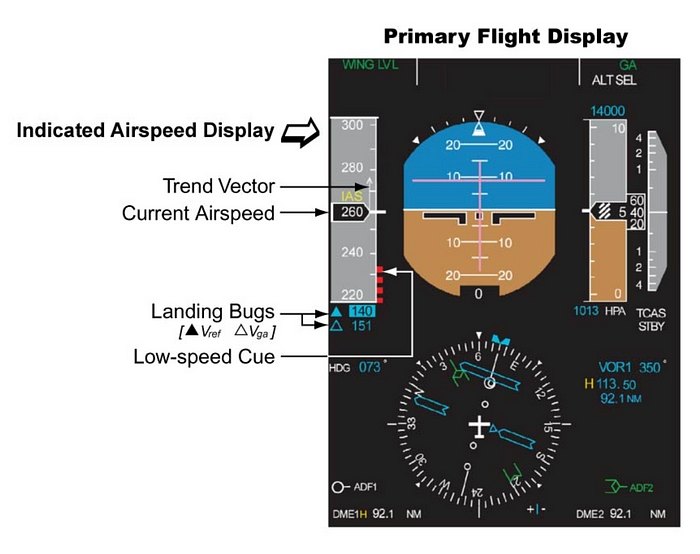

The reference speed switch (henceforth, the ref speed switch) is a unique feature of the Bombardier Q400 that was designed to prevent this kind of surprise stall. When set to the “INCR” (increase) position, the switch causes the stick shaker stall warning to activate at a lower angle of attack in order to pre-empt any reduction in performance. The switch also increases the height of the red and black “low speed” bars on the pilots’ airspeed indicators, which are designed to mark the speed at which the stick shaker AOA should be reached, as shown below. (The “reference speed” thus described in the name of the switch is the stick shaker activation speed.)

Although neither pilot on flight 3407 discussed moving the ref speed switch, they almost certainly did so at around this point. Thereafter, the flight reached its cruising altitude of 16,000 feet and proceeded normally as the pilots continued to discuss various matters, punctuated by First Officer Shaw’s periodic sniffling and sneezing. Eventually the topic turned to the question of whether Shaw should stay as a First Officer on the Q400 or seek an upgrade to Captain on the smaller Saab 340, with Captain Renslow offering various items of advice. “Well, think of it this way,” he said. “If you stayed on the Q, obviously you’re not making the Captain rate, but you might have better quality of life to begin with, with regards to buying a house and having a schedule to where, you know, you could work around, and you could be you know at home with your husband to take care of and all that kind of stuff…”

Shaw turned the conversation to her ambition to get hired at Alaska Airlines, which would allow her to be based closer to home. She also joked that a nightly cargo run to Spokane and back would be ideal — then she could have a family, some consistency…

Minutes later, at 21:51, Shaw listened to the automated weather broadcast for Buffalo and learned of strong winds, blowing from 250˚ at 15 knots with gusts to 23 knots, favoring runway 23. After discussing various aspects of the landing, including the planned flap setting of 15 degrees, First Officer Shaw submitted the landing data to a datalink service that would remotely calculate the appropriate reference speeds for the approach. Receiving the results back at 21:53, she announced that their landing reference speed, or Vref, would be 118 knots, among other items.

The landing reference speed is the speed at which the aircraft should cross the runway threshold to achieve the expected landing performance. The approach to the airport is typically carried out at a higher speed described in relation to Vref, such as “Vref + 5” or “Vref + 10.” When flying in icing conditions, where higher speeds may be required to account for any decrease in wing performance, the procedure on the Q400 was to increase the value of Vref by 20 knots with flaps 15. However, the datalink service would not add this 20-knot margin unless the pilot included the keyword “icing” during data entry, which Shaw apparently did not do. Consequently, the received Vref of 118 knots was meant for an approach without ice, while the Vref with ice should have been 138 knots.

The above discrepancy was going to become a significant problem because the approach to Buffalo would take place in icing conditions, which was why the pilots had set the ref speed switch to INCR. That meant that the stick shaker activation speed, which would normally be about 110 knots for their planned configuration, was now 131 knots. You can probably already see the problem: because the stick shaker activation speed was greater than their calculated Vref, the stick shaker would activate if they attempted to slow to their planned approach speed. However, no checklist or other procedure called for the pilots to cross-check their calculated approach speed with the position of the ref speed switch, nor did either crewmember independently notice.

By 22:00, flight 3407 had received permission to begin descending and was on its way down to 6,000 feet. Captain Renslow conducted the approach briefing, and First Officer Shaw checked in with operations and gave the passenger announcement. But as they descended further toward 4,000 feet, Renslow asked how Shaw’s plugged ears were doing and whether they were popping, skirting the boundaries of the sterile cockpit rule.

Moments later, spotting some ice beginning to accumulate, as expected, Shaw then asked, “Is that ice on our windshield?”

“Got it on my side,” Renslow said. “You don’t have yours?”

“Oh yeah, oh, it’s lots of ice,” Shaw said.

“Oh yeah, that’s the most I’ve seen — most ice I’ve seen on the leading edges in a long time,” Renslow commented. “In a while anyway, I should say.”

Then, without prompting, a thought popped into Shaw’s head, and the sterile cockpit rule seemingly melted away as she described her lack of experience with ice while working in Phoenix. “I had more actual time [in icing conditions] on my first day of [initial operating experience] than I did in the 1,600 hours I had when I came here,” she said. “I’m not even kidding. The first day!”

Captain Renslow should have shut down the unauthorized conversation, but instead he joined in. “Well that sounds — well, I mean I didn’t have 1,600 hours,” he said. “But uh as a matter of fact, I got hired with about 625 hours here.”

“That’s not much for back when you got hired,” Shaw said.

“No, but out of that six and a quarter, 250 hours was Part 121 turbine, multi-engine turbine,” Renslow said, referring to airline experience.

“Oh that’s right, yeah,” said Shaw. “No but all these guys are complaining, they’re saying ‘you know how we were supposed to upgrade by now’ and they’re complaining, I’m thinking you know what? I wouldn’t really mind going through a winter in the northeast before I have to upgrade to Captain.”

“No, no,” said Renslow.

“I’ve never seen icing conditions,” Shaw continued. “I’ve never de-iced. I’ve never seen any — I’ve never experienced any of that. I don’t want to have to experience that and make those kinds of calls. You know, I’d’ve freaked out. I’d’ve like, seen this much ice and thought, oh my gosh we were going to crash.”

At that moment, air traffic control called and said, “Colgan 3407, descend and maintain 2,300.”

First Officer Shaw acknowledged and set the autopilot to maintain 2,300 feet. Descending toward that altitude, both pilots attempted to continue the earlier conversation, interrupting themselves repeatedly to respond to radio calls and deal with lateral navigation. “But I — first couple of times I saw the amount of ice that the Saab would pick up and keep on truckin’,” Renslow said.

“Yeah,” said Shaw.

“I saw it on the spinner,” Renslow continued. “Ice coming out about that far, my eyes about that big around. I’m going, gosh. I mean, Florida, man, barely a little, you know, out of Pensacola.”

“Yeah,” Shaw said. “Holy cow, oh my gosh, oh yeah.”

At that moment, flight 3407 reached 2,300 feet, and the autopilot pitched up to level the plane. Realizing that amid their distraction they had not yet completed the descent checklist, Renslow said, “Let’s do a descent checklist please.” This checklist should have been done earlier, and now they would have to rush.

The pilots began to tick off one item after another. “Altimeters two niner eight zero, cross-checked,” said Shaw.

“29.80 set, cross-checked,” Renslow replied.

“Fuel balance check. Pressurization set and cabin PA complete. Descent checklist complete,” Shaw concluded.

Seeing as they were now very close to landing, Renslow said, “Alright if you want to go ahead we can do the approach checklist along with it.”

“Yeah, sure,” said Shaw. “Um, approach checklist, approach and landing briefing complete,” she began.

“Uh, complete,” Renslow read back.

“Bugs set,” Shaw said.

“Set,” said Renslow.

The bugs are a pair of adjustable markers on the airspeed indicators that the pilots can set to highlight important airspeeds for their approach. In this case, they set the primary bug to the Vref speed of 118 knots. Still, as before, neither pilot recognized that this value was below the stick shaker activation speed with the ref speed switch in “INCR.”

Rattling off additional items, Shaw said, “GPWS, landing flaps selected 15 degrees, fuel transfer off, hydraulic pressure and quantity check. Caution/warning lights check, seatbelt sign on and external lights on. Approach checklist complete.”

“Rock n’ roll,” said Renslow.

At around this time, the plane’s energy state was undergoing an important shift. Still flying level at 2,300 feet, flight 3407 was traveling at 180 knots, which was uncomfortably fast, so Renslow reduced power to near idle in order to slow down toward Vref. Subsequently, he ordered the landing gear down and the flaps to 15 degrees, greatly increasing drag. This combination of inputs caused the plane to slow rapidly, its airspeed plunging toward the stick shaker activation threshold. The black and red pole beside the airspeed indicator began to rise up, drawing ever closer to their actual airspeed, but no one seemed to be paying any attention. Furthermore, the Q400, like most turboprops, does not have automatic engine power control, so it was entirely incumbent upon Renslow, as the pilot flying, to increase power and hold the airspeed at the appropriate value. But for whatever reason, he did not observe the fast approaching low speed marker, instead allowing the speed to continue dropping toward their calculated Vref.

Moments later, at 22:16 and 26 seconds, as she was moving the flap lever through 10 degrees, Shaw possibly saw something odd, prompting her to say, “Uhhhh…”

One second later, as their airspeed fell through 131 knots, the stick shaker activated, rattling the pilots’ control columns to warn them of an impending stall, and the autopilot disconnected with a sudden alarm. In fact, the plane was not in imminent danger of stalling — the early activation of the warning was simply caused by the position of the ref speed switch. But the unexpected warning caught both pilots completely off guard, and their reaction was characterized by chaos and panic. Less than one second after the start of the warning, Captain Renslow grabbed his control column and hauled back to raise the nose — the exact opposite of the correct stick shaker response. When a plane is at risk of stalling, the number one priority is to reduce the angle of attack away from the critical value, which means lowering the nose and increasing airspeed. Instead, Renslow increased power and pitched up to 18 degrees — a response that was about to turn a false alarm into a real emergency.

When an airplane pitches up suddenly, it experiences an increase in positive G-forces, or load factor. Passengers can perceive this change as a sensation of increased weight, pressing them downward into their seats. As Captain Renslow pulled back hard on his controls, the plane began to climb with a load factor equivalent to 1.42 G’s, which would have made the passengers feel as though they weighed 42% more than normal. Critically, however, this increase in apparent weight applies to the aircraft as a whole, which means that lift also must increase by a proportional amount to maintain flight. To obtain this extra lift, a higher angle of attack is required for any given airspeed value, which means that the stall AOA will be reached at a higher airspeed than in normal, 1G flight. Because of this effect, as Captain Renslow pulled up, he caused the stall speed to increase from 105 knots to 125 knots, while their actual airspeed continued falling from 131 knots, at which point the stall speed and actual speed met in the middle, and the airplane stalled.

As the stall began, air stopped flowing normally over the ailerons, leading to a loss of roll control. The plane suddenly banked 45 degrees to the left, prompting Captain Renslow to exclaim, “Jesus Christ!” As he began banking back to the right, their altitude peaked, the nose began to fall through, and the plane started to descend, with stall and autopilot disconnect warnings still blaring, from a height of just over 2,000 feet.

At the same time, recognizing that the airplane had stalled, an automatic system called the stick pusher came to life to reduce the AOA by physically moving the pilots’ control columns forward. Designed to assist the pilot in recovering from a stall, the stick pusher is a crucial safety system, but it can be overridden if the pilot applies sufficient force, and that’s exactly what Captain Renslow did. As soon as the stick pusher kicked in, Renslow hauled back on his controls with 41 pounds of pull force, but since the plane was still stalled, the stick pusher then activated for a second and then a third time, which he fought with 90 and 160 pounds of pull force respectively. These actions forced the plane deeper into the stall as the airspeed decreased to just 100 knots. At the same time, the aircraft continued to roll uncontrollably, reaching an inverted bank of 105 degrees right, before reversing direction to 35 degrees left.

Plunging from the sky in a state of panic, the crew’s irrational actions continued. First Officer Shaw moved the flap lever back to 0 degrees and announced, “I put the flaps up,” which was inconsistent with the stall recovery procedure and made the situation even worse by decreasing the available lift. Captain Renslow then said something that might have been related to the landing gear, and Shaw asked, “Should the gear up?”

“Gear up, oh shit,” Renslow exclaimed.

Within seconds, they were out of altitude. Banked 25 degrees right and pitched 25˚ nose down, but descending almost vertically, the plane plummeted toward a quiet residential neighborhood in the Buffalo suburb of Clarence Center. “We’re down,” Renslow exclaimed, realizing that impact was imminent.

The cockpit voice recorder picked up the sound of a thump as the plane clipped some trees, and Shaw began to say, “We’re — ,” only to trail off into a scream of abject terror. A split second later, flight 3407 plowed directly into a house at 6038 Long Street in Clarence Center, and the recording came to an abrupt and disturbing end.

At the address in question, three members of the Wielinski family were at home relaxing for the evening when the sound of the approaching airplane shattered the nighttime calm. Before any of them could react, the Q400 plowed nose-first into the back of their house just above ground level, ripping from one end of the property to the other like an enormous wrecking ball, tearing the building to smithereens in a single, fiery instant. Fifty-three-year-old Karen Wielinski, who was watching TV in the living room, and her 22-year-old daughter Jill, who was separately watching television upstairs, both found themselves suddenly buried under broken pieces of the walls and ceiling, but each managed to escape before fire consumed the wreckage of what had moments earlier been their home. Unfortunately, Karen’s husband Doug was not so lucky: he had been in the kitchen, which took a direct hit from the airplane, and was probably killed instantly on impact.

The same fate tragically befell those on board the airplane. Although the aircraft had very little forward airspeed when it hit the ground, it was falling at such a rate that the resulting impact proved unsurvivable, and within moments fuel from the tanks and from a ruptured gas line inside the house sent fire sweeping through the wreckage anyway, destroying almost everything that remained. By the time firefighters arrived, a towering inferno had consumed both 6038 Long Street and the airplane, except for its tail section, lying almost intact and silhouetted against the flames. It was obvious that none of the 49 people on board could possibly have survived.

◊◊◊

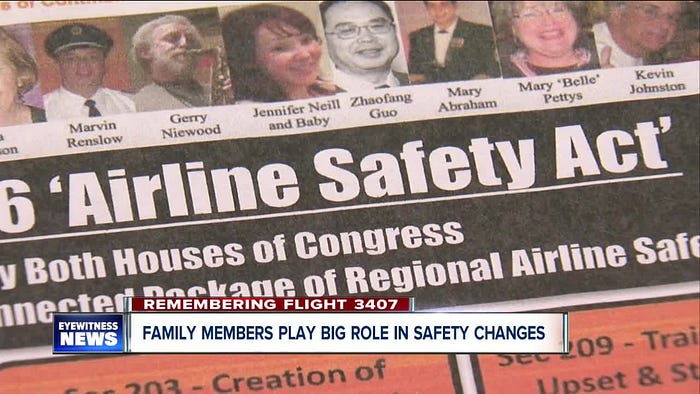

With 50 people dead, the crash was the deadliest in the United States since 2001, and the media attention it received was swift and overwhelming. The passengers came from many locations and walks of life, and included several musicians, rights activists, and religious leaders. Perhaps the most well-known victim was Beverly Eckert, a 9/11 widow and prominent survivor advocate who had met with President Obama just days before the crash. But the attention paid to the accident was not so much because of who was on it, but because the American public was exceptionally aggressive in asking why, in a country as rich and powerful as the United States, catastrophic plane crashes continued to occur. Decades earlier, plane crashes were often seen by the public as merely something that happened, but by 2009, they were rare enough that they had become something that was allowed to happen. That difference was highlighted by FAA safety official Margaret Gilligan in a retrospective interview with Bloomberg: “It came at a pivotal time [in which the public became] much less accepting of risk in aviation than it had been,” she said. “It took on a very different perspective than other accidents had up until that time.”

For the National Transportation Safety Board, these factors immediately positioned Colgan Air flight 3407 as the agency’s most pivotal investigation of the 21st century. The NTSB pulled out all the stops to complete the investigation before the first anniversary of the crash, in an analysis that went far beyond merely the events in the cockpit, ultimately tying together multiple industry-wide problems that created the conditions for the accident to occur — many of which the NTSB had been trying to highlight for years.

Despite early speculation that ice had caused the crash, the NTSB ultimately determined that the plane was controllable throughout the flight. In fact, a detailed reconstruction showed that the plane met or exceeded its expected performance at all times, and while the pilots did see ice building up on the windshield, the de- and anti-icing systems kept critical surfaces sufficiently clean that any ice that may have been present proved inconsequential. Instead, it appeared that Captain Renslow reacted to an unexpected and essentially spurious stall warning by pulling the nose up until the plane actually stalled, then held his controls in the nose-up position, prolonging the stall until they hit the ground. It was a shocking display of incompetence behind the yoke that left investigators scratching their heads.

The reasons why Renslow might have done this were manifold and speculative, but the NTSB presented a convincing explanation that ran right back to his initial flight training. Looking over his records, it was apparent that Marvin Renslow was not exactly the most competent pilot ever to grace the left seat of a Q400. In 1991, he was disapproved for his instrument flight rating after falling short in six different areas, and he required additional instruction before passing on the second attempt. In 2002, he was disapproved for his single engine land certificate due to insufficient performance in takeoffs, landings, go-arounds, and performance maneuvers, but again he passed on a second attempt. And in 2004, he was disapproved for his commercial multi-engine land certificate due to insufficient performance in all areas, only to pass, as always, on the second attempt. These three failed checkrides conducted by FAA examiners represented a pattern of difficulty with basic aspects of controlling the airplane, which persisted throughout his training period.

The NTSB was concerned to discover that when Renslow applied to join Colgan Air in 2004, he disclosed only his 1991 checkride failure, and completely omitted to mention the other two — an act that would have been a terminable offense if Colgan Air ever found out. However, while the FAA did retain his checkride results, which were available upon request, the company didn’t learn of his deception until after the accident because it simply never asked to see them. Airlines at that time were not required to request a pilot applicant’s FAA dossier before hiring them, and many companies declined to do so because the process was cumbersome and often failed to produce the requested documents until weeks after an applicant had already been accepted. If Colgan Air had used this system to check Renslow’s background, there is little doubt that it would never have hired him.

Nevertheless, there were plenty of red flags even after he arrived at Colgan Air. In order to prepare him for airline flying, the company sent him to a special academy run by Gulfstream International in Florida, which trained him to fly the twin engine Beech 1900. While at Gulfstream, he twice received unsatisfactory grades on simulated “approach to stall” sequences, and in another simulator session he let his speed drop more than 10 knots below Vref on approach. Instructors wrote that he struggled with maintaining altitude and airspeed, two of the most basic aspects of flying. Despite these deficiencies, he managed to graduate from the program and entered the right seat of the Saab 340, flying passengers around the southern US. But the poor results just didn’t stop. In 2006, he failed a routine proficiency checkride on the Saab due to unsatisfactory performance in five areas, including “general judgment.” And in 2007, Colgan Air sent him for training to acquire an advanced Air Transport Pilot certificate, which was required in order to upgrade to Captain, but he failed the checkride on his first try and had to take it again.

Over the course of their careers, most pilots will fail zero checkrides, sometimes one, and very occasionally two. By contrast, in only 3,300 hours as a pilot, Marvin Renslow had failed no less than five checkrides, which was practically unheard of in airline operations. And while he did conceal two of them, Colgan Air was aware of the other three, and the NTSB felt that the company should have started asking hard questions. But Colgan Air, and the industry overall, had no limit on the number of checkrides a pilot could theoretically fail, nor did the company have any kind of program to follow up on the performance of pilots who struggled in training. Whenever he failed a checkride, Renslow could simply take it again, and then Colgan would release him back onto the line with no follow-up whatsoever. The FAA had previously issued a letter called SAFO 06015 encouraging airlines to establish remedial training programs for poorly performing pilots, and asked its inspectors to ensure their airlines complied, but the FAA inspector assigned to Colgan Air said he had never seen the letter.

But that was only half the story. In fact, the NTSB found that Colgan Air’s Q400 training might have actively exacerbated some of Renslow’s greatest deficiencies, especially with respect to the situation he encountered on flight 3407.

The biggest problem was the way almost all airlines, including Colgan, taught pilots to deal with stalls. For most of history up to that point, flight simulators were not programmed to replicate the behavior of an airplane after it actually stalls, because limited data on this flight regime existed and it would be extraordinarily dangerous to gather more. Therefore, although new pilots were exposed to fully developed stalls during their initial training on single-engine aircraft, which can stall and recover easily, training on larger airplanes focused only on stall avoidance and not recovery. This took the form of “approach to stall” scenarios, in which the speed of the airplane steadily decreased and the angle of attack steadily increased until the stick shaker activated, at which point the pilot would step in to prevent the stall from occurring by increasing power and pitching down gently.

Until 2008, FAA evaluation guidelines called for instructors to mark an automatic fail if the trainee pilot lost more than 100 feet of altitude during this maneuver. This had created a negative training effect where many pilots began developing strategies aimed more at avoiding altitude loss than actually avoiding the stall. Although the FAA changed the guidelines to “minimal loss of altitude” in 2008, months before Renslow upgraded to the Q400, the NTSB found that some Colgan Air instructors were still telling trainees that they would fail if they lost more than 100 feet.

The problem with this type of training is that if the plane actually stalls, it will begin to descend rapidly, often in a flat attitude, with a high angle of attack, and the only way to reduce the AOA enough to recover is by pitching quite steeply nose down. This is obviously not compatible with an instinct to avoid altitude loss; in fact, trading altitude for speed is required. Although pilots learned about this difference in ground school, there was no opportunity to actually practice a nose-down stall recovery maneuver on a full-size airliner simulator — a potentially major problem, because as most flight instructors know, pitching down in a stall can be psychologically difficult. Most people instinctively want to pull the controls toward them as soon as the adrenaline starts pumping, like a driver white-knuckling the steering wheel. Theoretical training alone can be insufficient to reprogram this instinct in certain pilots, a fact that was borne out by a series of crashes, especially during the 2000s, that featured pilots who pulled up in response to a stall, including West Caribbean Airways flight 708 (August 2005) and Air France flight 447 (June 2009).

Experts were aware of this problem, and by the early 2000s NASA had produced wind tunnel data that was considered sufficiently accurate to form the basis for programming developed stall dynamics into flight simulators. In 2008, the FAA mandated that all future simulators incorporate these capabilities, but by the time of the accident hardly any of the new simulators were actually in use, and neither of the accident pilots were trained on them.

Lastly, another similar training blind spot was the stick pusher. Although all T-tailed aircraft are required to have stick pushers that force the nose down to prevent a stall, there was no requirement to demonstrate the system’s operation to pilots in training. Most Colgan Air instructors didn’t perform such a demonstration, nor was there any evidence that Renslow had ever seen the stick pusher in operation. Furthermore, one Colgan Air instructor who did demonstrate the system told the NTSB that around 75% of pilots initially responded to the stick pusher by attempting to override it, exactly as Renslow had done. Clearly the stick pusher could not live up to its role as a stall recovery aid if most pilots didn’t recognize that it was trying to help them.

Meanwhile, to understand why Renslow initially pitched up in response to the stick shaker, a theory was proposed that he might have been applying the recovery procedure for something known as a tailplane stall. Much like a wing, the horizontal stabilizer or tailplane is also an airfoil, albeit upside down, and can experience a stall if its AOA is too high. This typically only happens if the stabilizer is severely affected by ice, and even then only under very specific conditions. As a consequence, the stabilizer ceases to generate downforce on the tail and the plane pitches down rapidly, with accompanying symptoms such as buffeting. The recovery procedure is to apply a large nose-up input and retract the flaps. Furthermore, it was known that Colgan Air pilots, including Renslow, were shown a NASA video about tailplane stalls during training, which left varying impressions.

Some circumstantial evidence supported this theory, including the fact that Renslow knew they were flying in icing conditions, that he made large nose-up inputs, and that First Officer Shaw retracted the flaps. But the NTSB ultimately rejected this theory for a number of reasons. For one, the stick shaker does not activate in a tailplane stall, so it was unclear why Renslow’s immediate reaction to a stick shaker would be to apply the tailplane stall recovery procedure, an obscure maneuver that he had never practiced and which was not associated with any of the cues he was receiving. In fact, the speed with which he reacted — in less than one second — led investigators to seriously question the assertion that he spent any time diagnosing the problem at all. Nor did he ever express a belief that they were in a tailplane stall. Instead, investigators preferred the theory that he never attempted to apply any procedure, but simply manhandled the controls in a sudden state of panic.

The NTSB did note that according to Bombardier, it was impossible for a tailplane stall to happen on the Q400, and FAA experts testified that no airplanes currently flying passengers in the United States could experience tailplane stalls. Therefore, the NTSB urged the FAA to make sure pilots aren’t being taught about tailplane stalls that can’t happen, even though they determined that this negative training likely played no role in the accident. I also decided to address the topic in detail because a subset of the aviation community still expresses a sincere belief that the NTSB got it wrong and that Renslow thought a tailplane stall had occurred, an opinion that I don’t believe is borne out by the facts.

◊◊◊

The NTSB took the time to note that after Captain Renslow pulled up and stalled the airplane, it was not too late to recover with a prompt intervention by the First Officer. Unfortunately, this was not done, and in fact First Officer Shaw’s actions actively made the situation worse. When Captain Renslow failed to call for the stall recovery procedures, she did not attempt to remind him; she raised the flaps without prompting, worsening the stall; and she raised the landing gear before performing higher priority steps, like reducing the AOA. There was no reason to believe that Shaw was incapable as a pilot: unlike Renslow, she had never failed a checkride, and pilots who flew with her had only positive things to say about her ability. But she was clearly caught off guard both by the stall warning and by Renslow’s inappropriate reaction, and it didn’t seem that she ever fully understood what was happening. Her failure to more forcefully intervene was therefore attributed to surprise and confusion rather than any lack of assertiveness, which would be inconsistent with her reportedly confident personality. As for why she retracted the flaps, several theories were put forward, but the most convincing is that in a moment of great stress, she instinctively reverted to a habit she had developed during her days as a flight instructor. When instructing students on stalls, she would have retracted the flaps in stages during the recovery process as airspeed increased, without prompting from the student in the left seat. This resembled her behavior on the accident flight, where she raised the flaps unilaterally and prematurely, even though stall procedures called for her to raise the flaps only at the Captain’s command.

However, while the surprise stick shaker activation clearly contributed to the pilots’ loss of control, it shouldn’t have been a surprise in the first place — a fact that gave rise to an entirely separate area of inquiry.

As previously mentioned, the stick shaker activated because the pilots selected a Vref speed that was below the stick shaker activation threshold with the ref speed switch set to “INCR.” The switch was found in the wreckage still set to this position, and activating it was part of the standard icing procedure that Captain Renslow enacted during the climb. However, neither crewmember ever mentioned the switch during the flight, nor did they ever realize that it was the reason for the stick shaker. In part, the NTSB blamed Bombardier and Colgan Air for this lack of awareness. Neither the flight manual nor any company procedure included checking the switch’s position before calculating Vref, so the only safeguard against this exact scenario was the expectation that the pilots would remember the position of the switch and infer its consequences. This gap was inconsistent with modern procedural design practices and should have been closed.

This omission could have been predicted if the pilots had more closely monitored their airspeed indicators, and in particular the relationship between their actual airspeed and the red and black “low speed” bar. Part of the problem was that monitoring is an inherently difficult job, and Colgan Air was not teaching its pilots to use industry best-practice monitoring strategies — nor was it required to. Furthermore, the Q400 did not have, and was not required to have, certain airspeed monitoring aids that exist on other aircraft. On the Boeing 777, for instance, an amber bar appears above the red “low speed” zone, in which the airspeed value in knots is also displayed in amber in order to draw the pilot’s attention before the stick shaker activates. It’s unknown whether such a feature would have helped on flight 3407, but the possibility couldn’t be ruled out.

Nevertheless, the NTSB also believed that the pilots’ loss of airspeed awareness was in part due to their continuous off-topic conversation, which continued even after descending below 10,000 feet. Although conversations above 10,000 feet are perfectly legal, the extent of the discussion might have reduced their attentiveness to the developing issue. And later, after descending through 10,000 feet, repeated violations of the sterile cockpit concept resulted in a delay to the descent checklist and a general compression of tasks near the very end of the flight. This led to a high workload for First Officer Shaw in the minute before the stick shaker, reducing her ability to monitor their falling airspeed. Furthermore, the NTSB found it noteworthy that the pilots observed ice on the windshield but did not discuss its potential threat to the aircraft. At that point the pilots probably should have discussed whether to use the icing approach speed of Vref + 20 knots. If they had, then the airspeed might not have been allowed to drop low enough for the stick shaker to activate, even if they forgot all about the ref speed switch.

The full-throated violation of the sterile cockpit rule by both pilots was indicative of a serious problem with flight deck culture. Other Colgan Air pilots claimed that violations were rare, but Colgan had no way of verifying this, and the ease with which the pilots of flight 3407 ignored the rule suggested that the practice was habitual. The NTSB had made similar findings in other accidents in the 2000s as well, and investigators believed that violations were more common than most in the industry wanted to admit.

On the level of individual crews, ensuring adherence is the responsibility of the Captain. But the leadership skills required to lay down the law don’t just appear when another stripe is added to a pilot’s uniform. These qualities must be taught, and in this area Colgan Air fell massively short. The airline provided about 8 hours of training ostensibly about leadership for new Captains, but three quarters of this time was devoted to the new administrative duties and paperwork that Captains were expected to complete, with only about two hours left to cover lofty topics like instilling crew discipline, making judgment calls, and so on. This was obviously inadequate, especially for a regional airline. Companies like Colgan Air are treated as stepping stones to careers at the major carriers, so turnover is very high, and brand new pilots often upgrade to Captain after a year or less with the company. That isn’t enough time to acquire leadership qualities, and Colgan Air’s failure to emphasize this area was nothing short of myopic.

◊◊◊

Another key component of the accident — and perhaps even the most important one — was undoubtedly fatigue. The crash happened at 22:16, which was Captain Renslow’s normal bedtime. By that time he had also been awake for at least 15 hours, which is around the time most people’s ability to focus starts to drop off. Renslow had also spent the previous night on a couch in the crew room, which was not an environment conducive to restorative sleep. Similarly, First Officer Shaw slept in at least three distinct segments, of which two were on board cargo planes flying cross-country from Seattle, and the third was also in the crew room during daylight hours. As a result, both pilots probably received very low quality sleep and were probably tired throughout the trip to Buffalo, reducing their ability to effectively monitor the flight. First Officer Shaw’s worsening head cold would have compounded her fatigue further, and Renslow could be heard yawning on the cockpit voice recording.

Unfortunately, this story was quite familiar to many regional airline pilots across America. The majority of airline pilots commute to work, and in 2009 the problem was especially acute at places like Colgan Air’s Newark hub, where desperately low wages for First Officers ran into steep local housing costs. Management personnel at Colgan Air had their pay adjusted for local cost of living, but pilots did not. Many couldn’t afford to live in Newark even if they wanted to, but because Colgan Air was not responsible for accommodating pilots at what should be their home base, they were still expected to find overnight lodgings between trips at their own expense. Over the course of a year, hotel costs alone could consume a substantial percentage of a Colgan Air pilot’s meager salary. Around the country, regional airline pilots tried to solve this problem by pooling their resources to rent apartments for use as “crash pads,” where up to a dozen pilots would split the rent, fill every room with bunk beds, and use the space to sleep between flights or after commuting in. But even this scheme could be pricy in places like Newark, and neither Captain Renslow nor First Officer Shaw had a crash pad. Renslow had told a fellow pilot that he was concerned about the expense and preferred to bid on trips that would avoid overnight stays in Newark. As for Shaw, she had a more immediate concern: at that time, only 4% of US airline pilots were women, and she couldn’t find enough female pilots at Colgan to create a women-only crash pad even before taking cost into consideration.

Despite the reality that many of its pilots were struggling to afford overnight lodgings, Colgan Air did absolutely nothing to mitigate the problem. Some airlines provided help finding affordable housing or offered quiet sleeping areas at airports, but Colgan did neither. The chief pilot at the Newark base was barely aware that most pilots were commuting from other cities, and work schedules paid no heed to whether a pilot lived in Newark or not. Many pilots apparently resorted to sleeping in the Newark crew room, but in 2008 the chief pilot sent out a memo stating that the practice was “strictly prohibited” and would result in “severe disciplinary consequences, up to and including termination.” The airline even created a policy of leaving the lights in the crew room turned on throughout the night to make it harder to sleep there. But despite the chief pilot’s strongly worded letter, the rule was completely unenforced and it did not appear that anyone was ever punished, nor did the practice stop.

The problem also extended to pilots’ ability to call in sick. First Officer Shaw was clearly unwell during the flight, but didn’t call in sick because she would have to pay for a hotel. It was also possible for pilots to call in fatigued, but they were required to provide the chief pilot with paperwork explaining why, and could face negative consequences if management didn’t like the reason. An inability to afford suitable accommodations in Newark was not an excuse — and besides, if pilots called in fatigued because they had slept on a cargo plane or on a couch in the crew room, they would never complete a flight!

◊◊◊

In summary, the findings were damning. A Captain with five failed checkrides. A poorly documented switch. Inadequate and misleading training. A work and living environment that made fatigue unavoidable. Lax FAA requirements. Taken together, these myriad failures and deficiencies began to paint a picture of a crash that was almost bound to happen. And when this story was made public, the nation was outraged — as you may well be yourself, having read this far. The takeaway was that the entire structure of America’s aviation system enabled the tragedy in Buffalo. From coast to coast, from top to bottom, no one was spared. Congressional hearings were held, documentaries were made, the families of victims picketed in Washington. And for the first time in years, if not decades there seemed to be something like a consensus that things needed to fundamentally change.

In the end, the changes would prove to be sweeping. Built in part on a list of more than 25 NTSB recommendations, in August 2010 the US Congress passed the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act, mandating a comprehensive list of improvements that would ultimately affect most corners of the industry. The full laundry list of changes is too extensive to list here, but key points included the following:

· Airline ticket sellers must disclose the operator of contracted flights to the customer at the point of sale.

· The FAA must publish an annual report describing its plans to respond to every open NTSB recommendation.

· The FAA must create a single, searchable pilot records database that will allow airlines to quickly discover an applicant’s past employers, training records, and disciplinary history. (The FAA struggled to fully comply, but the last components of the database finally came online in 2022.)

· The FAA must convene a task force to improve and standardize flight crew professional training, with yearly reports to Congress.

· The FAA must ensure that all airlines have pilot mentoring programs, professional development committees, recurrent command and leadership training, and programs generally suited to the experience levels and career stages of the pilots they employ.

· The FAA must require that all airlines provide upset and recovery training to help pilots recover from unusual aircraft attitudes. (These programs were finally able to cover all US airline pilots in 2019, when high-fidelity simulators became sufficiently widespread.)

· The FAA must require that all airlines have remedial training programs for poorly performing pilots.

· The FAA must find ways to improve pilot responses to stick pushers and icing conditions.

· The FAA must strengthen flight and duty time limits and ensure that all airlines have a fatigue management program. (The FAA ultimately increased the minimum rest time between flights from 8 hours to 10, introduced limitations related to time zone crossings, increased the minimum consecutive off-duty hours that must be granted each week, and clarified that preventing fatigue is the joint responsibility of the pilot and the airline, and not solely the pilot.)

· The FAA must require all airlines to have a Safety Management System, and encourage them to have a Flight Operations Quality Assurance System. (An SMS and a FOQA are both systems that use flight data, anonymous reports, and other sources of information to analyze safety trends and correct recurring issues before they lead to an accident. Colgan Air had neither of these. Also, in a darkly funny detail, the company had set up an anonymous reporting system that was literally never used — not even once — and they did not appear to see a problem.)

Separately, Colgan Air made numerous changes to procedures, training programs, and policies, but was ultimately merged into Pinnacle Airlines in 2012.

◊◊◊

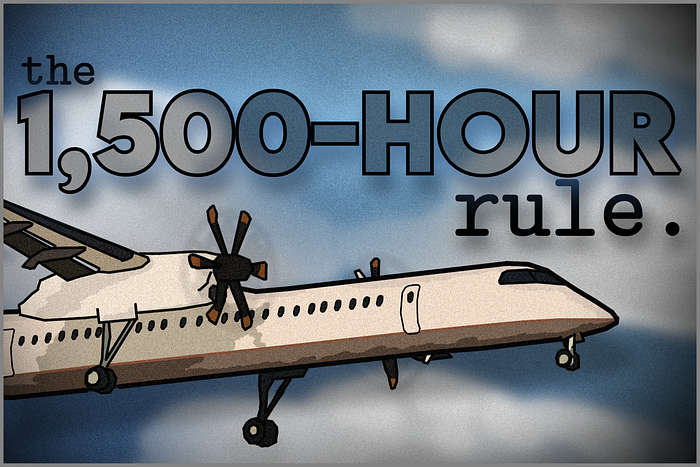

These new rules alone were game-changing for aviation safety. But the one everyone is here to talk about — and I thank you deeply for sticking around long enough to get to this part — is the so-called 1,500 hour rule.

The Aviation Safety Act of 2010 didn’t actually say anything about “1,500 hours.” Rather, it required that every airline pilot hold an Air Transport Pilot certificate, or ATP, which was previously only required for Captains. An ATP is the most advanced certificate obtained by commercial pilots and requires a higher level of training than the Commercial Pilot certificate typically held by First Officers prior to the Colgan Air crash. But the requirements to earn an ATP were also quite different before this part of the Act went into effect in 2013, because the FAA decided to use the ATP certification process to ensure that pilots gained a number of critical skills before ever setting foot in the cockpit of a scheduled passenger flight.

Before continuing, it helps to know a little bit about how the aviation industry as a whole is structured in the United States. The bottom rung is governed by Part 91 of the Federal Aviation Regulations, applying to private, general aviation and a few low level airplane-for-hire businesses. Most Part 91 pilots hold only a Private Pilot’s License and fly recreationally.

The next level up is Part 135, which applies to charter and air taxi services. In practice this includes most on-demand air transport, and a small amount of scheduled air transport involving very small airplanes. Flying under part 135 requires a Commercial Pilot certificate but an ATP is only required for Captains on multi-engine aircraft or aircraft with more than 10 passenger seats.

Finally, the highest level is Part 121, which is what most people think of when we say the word “airline.” It’s highly likely that every airline that the average person has heard of operates under Part 121. The Aviation Safety Act of 2010 specifically required that all Part 121 pilots, and not just Captains, possess an ATP certificate.

The FAA ultimately tailored the revamped ATP certification process to prepare pilots for the specific realities of Part 121 operations. This move was intended to address what the FAA’s First Officer Qualification Rulemaking Committee determined was a “knowledge gap” between the regulatory expectations for Part 121 pilots, and the actual abilities of Part 121 First Officers, regardless of whether they had an ATP. As a result, the FAA stipulated, beginning in 2013, that a pilot seeking an ATP must have 50 flight hours in a multi-engine airplane; complete a special FAA-run ATP certification program including simulator training; complete both academic and simulator training on aerodynamics, stall and upset prevention and recovery, meteorology, automation, air carrier operations, transport airplane performance, professionalism, and leadership and development; and demonstrate an ability to “function effectively in adverse weather conditions, during high altitude operations, in an air carrier environment, and adhere to the highest professional standards.”

And last but definitely not least, the total number of flight hours required to earn an ATP was increased to 1,500, or 1,000 with a bachelor’s degree in aviation, or 750 with military aviation experience.

Right off the bat, it should be made clear, first of all, that the 1,500 hour rule is really the “ATP rule;” second, that the NTSB never identified pilot experience as a problem in the Colgan Air crash; and third, that both of the pilots involved in the Colgan Air accident had more than 1,500 hours at the time, and in fact Shaw had almost 1,500 already when she was hired. In fact, no pilot involved in a fatal Part 121 accident attributed to pilot error between 1991 and 2010 had under 1,500 hours. But, as it turns out, all of that might be beside the point.

It’s critical that I preface this section by noting that I am not a commercial pilot, and the following is my impression based on academic studies, articles, and interactions with actual airline pilots, and may not be reflective of everyone’s diverse experiences. But it appears that the biggest effect of the ATP rule was not on the number of hours accumulated by newly hired first officers at regional airlines, but rather on overall pilot quality of life — and the change was overwhelmingly positive.

Initially, many in the industry were concerned that no one would want to become a pilot if they had to spend two or three years and thousands of dollars racking up 1,500 hours just to land a Colgan Air job with a salary that qualified them for food stamps. However, the market predictably responded. Within a few years, the median salary for regional airline First Officers approximately tripled, and has continued to grow ever since. Anecdotally, salaries at some regional airlines have surpassed $100,000 a year (and pilots, feel free to correct me if this assessment is overly conservative). In turn, the financial pressures that forced regional airline pilots like Rebecca Shaw to take dangerous shortcuts to avoid lodging expenses have been noticeably reduced. And the knock-on effect has boosted salaries for pilots at major airlines as well.

Nevertheless, there remains a certain amount of discontent surrounding the ATP rule. Regional airlines argue that it contributes to an ongoing pilot shortage by making it prohibitively expensive and time-consuming to qualify, and regional carrier SkyWest recently went as far as to explore re-registering under Part 135, possibly in order to skirt the requirement. On the other hand, the Air Line Pilots Association, the largest American pilots’ union, has always argued that there is no such thing as a pilot shortage, and that regional airlines should simply increase pay if they’re having trouble attracting applicants. However, regional airlines often have low fixed profits: major carriers pay them flat rates per flight with few ways to increase revenue other than adding flights and reducing expenses, which incentivizes a cost-cutting mentality and makes them reluctant to follow ALPA’s advice. In a 2019 statement, the union forcefully denounced this tendency among regional airlines, writing, “Despite the many safety advancements that have been enacted, there are some industry stakeholders actively lobbying Congress and the FAA for a weakening of these vital rules purely for financial gain… Unwavering from their commitment to enhance aviation safety, nearly 100,000 airline pilots have actively opposed legislation to weaken these safety rules through ALPA’s Calls to Action, and some 40,000 individuals have sent letters to Congress to stop any attempts to diminish these critical safety regulations.”

Approaching the issue from another angle, however, plenty of voices in the industry have questioned whether the 1,500 hour requirement within the ATP rule actually made flying safer.

A key element of context for this debate is that Part 121 operations in the United States have achieved a completely unprecedented level of safety in recent years. Colgan Air flight 3407 was the last fatal crash of a Part 121 passenger flight in the United States, and in the nearly 15 years since, there have only been two passenger fatalities — both due to flying engine debris — even as US airlines carried literally billions of people. It is in no way hyperbole to say that this record is the best in the history of global aviation. However, this extraordinary success has surprised aviation experts, and there doesn’t seem to be a firm consensus as to why there hasn’t been a crash in such a long time. Everyone I’ve talked to seems to have their own pet theory, but the most popular answer by far is that the Aviation Safety Act of 2010 deserves the lion’s share of the credit, and I’m inclined to agree.

Nevertheless, the question remains: has the 1,500 hour requirement to receive an ATP played any role? This is inherently a hard question to study. It’s difficult to know how many crashes a rule prevented, because it’s hard to collect data on a crash that didn’t happen. Furthermore, in the absence of a control group, it’s almost impossible to prove that other changes made at the same time weren’t wholly responsible. Probably for these reasons, I was unable to find any academic studies that actually tried to make this connection. However, I did find several studies that tried to connect the 1,500 hour requirement to certain indicators, like training completion rates, that could serve as a facsimile for overall pilot quality.

As a disclaimer, I do not know who funded these studies, nor can I vouch for their conclusions. But in general, the studies suggested, narrowly speaking, that the 1,500 hour requirement has little or no relationship with the selected safety indicators.

One of the most extensive studies has been described in a series of papers called the Pilot Source Study published by the Aviation Accreditation Board International, an industry group that evaluates collegiate aviation programs. In the 2013 version of their Pilot Source Study, they found that among over 6,000 regional airline pilots, those who had a Commercial Pilot certificate but not an ATP at the time of hire were more successful in training than those who built up the hours for an ATP, supposedly because the latter group spent more time prior to airline employment flying small aircraft in ad-hoc environments that led to an accumulation of bad habits. (It should be noted that this was before the new ATP training requirements actually went into effect.) Subsequently, in a 2018 follow-up, the same group found that among pilots with a four-year degree in aviation, the amount of extra training required following employment at an airline was simply correlated with elapsed time since graduation, which possibly explained the previous findings. The takeaway is just that the need for extra training increases as a pilot is farther removed from their initial aeronautical education, regardless of their qualifications.

Another study (Shane 2015) found that pilots who entered initial training at a specific regional airline after the ATP rule, compared to those who entered before the ATP rule, were more likely to wash out or require extra training to meet requirements. However, the difference was entirely observed among pilots who had over 1,500 hours already when they were hired. Those who entered the airline business with less than 1,500 hours after the passage of the rule, such as military pilots and those with college degrees, performed just as well as those with under 1,500 hours before the rule. As for why pilots with more hours might perform worse, see the previous paragraph.

Meanwhile, yet another study (Maas 2022) found that the average flight hours of Colgan Air pilots at date of hire actually went down after passage of the ATP rule because the market was previously saturated with applicants of varying experience levels but not necessarily with ATPs. Subsequently, the airline scrambled to hire anyone at all with an ATP, which turned out to be mostly students with 1,000 hours and a four-year degree. However, it’s unclear why this is supposed to be a bad thing, given the previous observation that pilots straight out of university are less likely to fail. Furthermore, one of the key findings of the Pilot Source Study was that quality of hours is better than quantity, so Maas might have been pursuing an inappropriate metric.

Lastly, taking a slightly different approach, a fourth study (Depperschmidt et al 2018) surveyed faculty at collegiate flight training programs and found that 93% of them believed the 1,500 hour requirement did not improve US air carrier safety, and many also believed that more flight hours at that stage of a pilot’s career progression did not improve piloting skill. The opinions of such an overwhelming majority of instructors obviously hold considerable value, but the study didn’t include data that would confirm or refute their beliefs.

In addition to these studies, I’ve heard a number of other arguments against the 1,500 hour requirement. One of the most relevant for me is the assertion that it forces young, inexperienced pilots into Part 91 and Part 135 jobs with thinner safety nets and harsher working conditions in order to build hours for their ATP, where a disturbing number perish in accidents before reaching their goal. I personally lost a friend under these exact circumstances — a young man who dreamed of going to the airlines, but lost his life in a Part 135 crash at the age of 23. But despite the emotional pull of this argument, I have to point out that this was exactly how it worked before regional airlines positioned themselves as a vehicle for young pilots to gain experience, and there is no evidence that Part 135 operations have gotten more dangerous since the return of this model. In fact, the opposite appears to be true.

Finally, a minor point in favor of the 1,500 hour requirement is that many young pilots gain those hours by flight instructing, teaching slightly younger pilots who will then replace them as instructors after a couple years. The original Pilot Source Study in 2010 found that pilots who had flight instructor experience performed better than those who didn’t, so this practice should be slightly boosting overall pilot quality.

So what’s the verdict — is the 1,500 hour requirement good or bad? I would contend that it’s just not that simple. Despite a relative lack of evidence that the 1,500 hour requirement itself has increased safety, it has clearly increased quality of life for airline pilots. Furthermore, most studies claiming that the requirement has been detrimental to safety appear flawed. My personal opinion is that the specific number of hours — 1,500 — is probably arbitrary, and could be changed with few significant safety consequences in either direction. However — and this is where the public discourse tends to break down — the same absolutely cannot be said of the ATP rule as a whole. The actual training requirements to receive an ATP are rigorous, important, and useful, and there’s no doubt in my mind that there are major benefits to experiencing things like upset and recovery training, leadership and development coaching, and other aspects of the reformed program, before entering Part 121 operations. I can’t prove that these experiences have contributed to America’s modern safety record any more than I can prove the 1,500 hour requirement hasn’t, but it’s very difficult to argue that they aren’t things every commercial pilot should undergo. For that reason, repealing the ATP rule just to remove the 1,500 hour barrier would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

◊◊◊

In the end, the legacy of Colgan Air flight 3407 and the Airline Safety Act is still playing out, and some of the resulting debates may never be settled. But there can be no doubt that the crash was the most influential US accident of the 21st century so far, and arguably the most influential ever, given the scope of the changes that followed. The reforms have made flying safer, made life better for pilots, and restored a great degree of confidence in America’s aviation system. And none of that would have been possible without the dogged efforts of the victims’ families, who took the fight to the halls of Congress and made it clear that enough was enough.

As we look to the future, however, certain uncertainties remain. When it comes to the 1,500 hour rule, a popular joke is that pilots with more than 1,500 hours love it and those with less than 1,500 hours hate it, and that might always be the case. But regional airlines detest it too, and it’s concerning that some of them are seeking to circumvent the ATP rule entirely rather than merely lobbying for a lower flight hour requirement. This behavior is a reminder that the reforms shouldn’t be taken for granted. They were forced upon the industry by Congress after years of deadlock, overruling FAA feet-dragging and airline lobbying to build the system we have today. And the longer we go without a major Part 121 accident, the more we can point to that brute force approach and say that it worked, that we created a system that’s safer than experts ever imagined. The value of that success is immeasurable, and with few scientific ways to say precisely what underlies it, we had best think long and hard before rolling back any changes. As they say — if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

_______________________________________________________________

As a quick note, I could have written an article twice this long if I wanted to go deep into the enduring problems of the regional airline industry. However, future plans exist to do just that on my new podcast (with slides!), Controlled Pod Into Terrain, where I discuss aerospace disasters with my cohosts Ariadne and J. Check out our channel here, and listen to our latest episode, featuring UPS flight 006

Alternatively, download audio-only versions via RSS.com, or look us up on Spotify!

_______________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit

Support me on Patreon (Note: I do not earn money from views on Medium!)

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 250 similar articles

_______________________________________________________________

Note: this accident was previously featured in episode 58 of the plane crash series on October 13th, 2018, prior to the series’ arrival on Medium. This article is written without reference to and supersedes the original.