Contract to Kill: The crash of Surinam Airways flight 764

On the 7th of June 1989, a Surinamese DC-8 on approach to the tiny country’s main airport crashed short of the runway, killing 176 of the 187 passengers and crew, including fifteen professional football players and several high-ranking military officials. The crash plunged Suriname into mourning — with a national population smaller than that of most mid-sized cities, it seemed like everyone in the country knew someone on the plane. The scale of the tragedy was unlike anything Suriname had ever seen. As a specially appointed commission of inquiry launched its investigation into the disaster, it soon became apparent that something was very much amiss with the crew. The investigators would soon discover that each of the pilots had an absurd history of incompetence and deception, and that they had attempted to fly an approach for which they had not been cleared using a navigational aid which was down for maintenance. Lurking behind this entire sequence of events was a shadow industry of “pilot brokers” based out of Florida which had been contracting unqualified American pilots to foreign air carriers for years without getting caught.

Suriname is a small country on the northern coast of South America, sandwiched between Guyana, Brazil, and French Guiana and dominated by the vast wilderness of the Amazon rainforest. In 1989, the population of the country was just 400,000, almost all of whom lived (and continue to live) in the capital city, Paramaribo. A former Dutch colony, Suriname only gained independence in 1975, and by 1989 the Netherlands still wielded massive cultural influence over the country. Despite its small size, Suriname has had its own state-owned airline since 1955, known in English as Surinam Airways and in Dutch as Surinaamse Luchtvaart Maatschappij (SLM), which operates a small fleet of jet airliners on international routes to and from Paramaribo. The most important of these routes has long been the airline’s direct flight to Amsterdam, which it operates today using a Boeing 777ER. In 1989, its fleet was considerably less advanced: the workhorse plane that flew back and forth between Paramaribo and Amsterdam was an aging four-engine Douglas DC-8 built in the United States in 1969.

Due to a lack of qualified pilots in Suriname, during the 1980s Surinam Airways routinely hired pilots on contract from the United States. Among these pilots were 66-year-old Captain Wilbert “Will” Rogers, First Officer Glyn Tobias (age unknown — more on that later!), and 65-year-old Flight Engineer Warren Rose. Rogers was past the mandatory airline pilot retirement age of 60 years, but Surinam Airways didn’t even know his name, let alone his age. All three pilots had been furnished by a company based in Miami, Florida called Air Crew International, which agreed to provide qualified DC-8 crews on a contract that was renewed weekly. Crew training, salaries, and examinations were all the responsibility of Air Crew International, while Surinam Airways provided the plane and the flight attendants.

Captain Rogers, First Officer Tobias, and Flight Engineer Rose were scheduled to fly the regular flight from Amsterdam to Paramaribo on the 6th of June 1989. However, the flight was delayed for twelve hours at Schiphol Airport after the plane was late arriving from Miami. Surinam Airways flight 764 finally departed Amsterdam at 11:25 p.m. local time, and the passengers settled in for the nine hour trip to Paramaribo. Among the passengers that night were a group of Dutch-Surinamese football players representing an informal club team called the Colourful XI. The club was the brainchild of social worker Sonny Hasnoe, who wanted to keep young people out of trouble and encourage integration by plucking boys from the roughest majority-Surinamese neighborhoods of Amsterdam and drafting them into football teams. The initiative eventually attracted the attention of some of the Netherlands’ biggest football stars, of whom several players of Surinamese ancestry came together to form the so-called Colourful XI. The Colourful XI played their first formal match against the Surinamese football team SV Robinhood in Paramaribo in 1986, after which more games were scheduled. A four-team tournament had been planned for the week of the 7th of June 1989, but the Dutch club teams to which many of the players belonged were reluctant to allow them to make the transatlantic journey to Suriname, which some of the club managers called “unnecessary.” As a plan B, it was decided that 18 Colourful XI back-benchers would fly out instead. Two of the starting players also defied their managers and flew to Paramaribo themselves on an earlier flight.

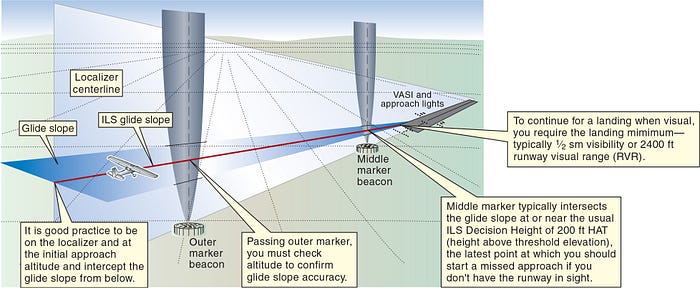

The overnight flight proceeded normally until around 4:00 a.m. local time on the 7th of June (8.5 hours into the flight), when the crew began their descent toward Zanderij Airport, located in a rural area some 40 kilometers south of Paramaribo. The pilots planned to approach runway 10 from the west. This runway normally had an instrument landing system (ILS) that could guide the plane down to within sight of the threshold, but it had been out of service since December 1988, a fact of which the pilots were well aware. They didn’t expect this to be a big problem: after all, runway 10 also had the equipment for a VOR/DME approach, where the crew flies toward a VOR beacon at the airport while descending manually in a series of step-downs at prescribed distances from the runway. Visibility was 6,000 meters with scattered fog and a layer of strata at 400 feet, within limits for the VOR/DME approach.

But as flight 764 descended into Paramaribo, the pilots received the 4:00 weather report, which revealed that the visibility had decreased dramatically to just 900 meters. “What happened with the six kilometers?” Captain Rogers exclaimed. After a brief discussion, it soon became apparent that the minimum visibility for a DC-8 on the VOR/DME approach was 2,300 meters, and that with 900 meters visibility, they wouldn’t be able to land using this procedure.

The pilots began to consider whether they had enough fuel to hold and wait for the weather to improve, but then First Officer Tobias jumped in with a sneaky suggestion: “We don’t legally have an ILS,” he said, “[But] we have to use it.” The minimum visibility on the ILS approach to runway 10 was 800 meters, which would allow them to land. According to the active Notice to Airmen (or NOTAM) describing the status of the airport equipment, the ILS was not serviceable. But the pilots knew for a fact that the system was still turned on and it was possible to pick up the signal. Captain Rogers agreed that they should use the ILS, which would also come with a minimum descent altitude (MDA) of 260 feet, allowing them to descend below the layer of strata and catch sight of the runway.

Moments later, First Officer Tobias remarked, “You can see the town over there.” After another two minutes, he commented, “It must be very localized,” referring to the fog, which was apparently patchy enough for him to catch sight of the lights of Paramaribo.

“We’ll take a shot at it,” said Captain Rogers. He too believed that they might be able to find an opening in the fog which would make it easier to land.

Four minutes later, he seemed to be proven right as First Officer Tobias caught sight of the runway lights in the distance. “That’s right, here visibility won’t be any problem,” he said.

“Make a pass and we’ll land, that’s all,” Rogers replied.

At around 4:17 a.m., the Paramaribo controller cleared flight 764 to perform a VOR/DME approach to runway 10. First Officer Tobias acknowledged the clearance, but the pilots had no intention of performing a VOR/DME approach. Captain Rogers tuned his equipment to pick up the signal from the ILS, while instructing Tobias to set up his instruments for the VOR/DME procedure to use as a backup in case the ILS didn’t work. Now they began a turn to line up with the runway — only Captain Rogers didn’t seem to be entirely clued in to where they needed to go. First Officer Tobias didn’t think he was turning steeply enough, so he said, “Just keep on coming around on the thirty degree bank there, you’ll be alright,” adding moments later, “Get it on up to thirty degrees!”

“Two thousand feet,” announced Flight Engineer Rose.

“Huh?” said Rogers.

“Two thousand, two thousand,” Tobias repeated.

With Tobias providing information on where to fly, the crew maneuvered the DC-8 into position to pick up the signal from the ILS. At 4:23, Rogers’ instruments began to pick up the signal from the localizer — a directional beam broadcast by the ILS along the extended runway centerline which helps the plane align with the runway. Shortly thereafter, the tower cleared flight 764 to land.

Now partially on the ILS, Tobias kept an eye on the view out the window. At around 4:24 he said, “A little bit of low fog coming up, I reckon just a little bit. Okay, it’s right, right down there close to the runway.” Apparently fog was beginning to obscure his view of the runway lights. The tower twice asked whether the crew could see the runway, and Tobias replied in the affirmative, but at that moment the plane was descending through the strata and it was unlikely they could have seen much.

At 4:25, the glide slope indication began to move, proving that the signal from the system was nearby. The glide slope, which along with the localizer forms the ILS, is meant to guide the plane down at the precise angle needed to arrive at the runway. The position of the glide slope relative to the airplane is displayed on the horizontal situation indicator using a pointer that moves up and down on a scale. When the pointer is centered on the scale, the plane is on the glide slope, and the glide slope is said to have been “captured;” if the pointer is below the center, the plane is too high, and if the pointer is above the center, the plane is too low.

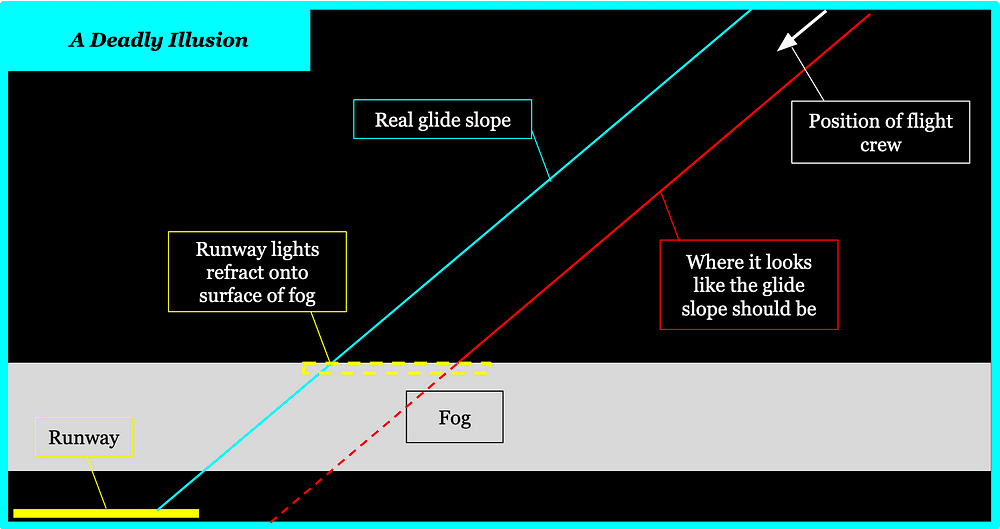

By this point the pilots could see the lights of the runway dimly glowing through a dense layer of fog. But as the light refracted through the fog layer, it illuminated the surface of the layer and created an illusion that the runway was closer than it actually was. This made it look like they were coming in too high, directly contradicting the horizontal situation indicator, which showed them below the glide slope.

“That ILS is slightly off there on the indication,” Tobias remarked.

“If I get a capture here I’ll be happy,” said Rogers.

“On glide slope, just above,” said Tobias.

“I didn’t get no capture yet,” Rogers replied. How could Tobias say they were almost on the glide slope if the pointer wasn’t centered?

“No, I know it, I don’t trust that ILS,” said Tobias. “I think you’re… according to that runway, you look like you’re high.” Apparently his determination that they were on or slightly above the glide slope came from his own judgment, not from any actual instrument indication — he just thought the glide slope wasn’t working properly and took a guess at where it was supposed to be. In fact, the glide slope was working just fine, and he had made a grave error of judgment.

As Captain Rogers pitched down to try to reach where he thought the glide slope should be, the ground proximity warning system (GPWS) began to call out, “GLIDE SLOPE,” informing the crew that they were deviating further below the descent path.

“Five hundred feet,” said Flight Engineer Rose.

“GLIDE SLOPE,” said the GPWS. “GLIDE SLOPE!”

Already convinced that the unserviceable ILS was giving them a false reading, the crew had little patience for this loud, annoying alarm. One of the pilots reached around and pulled the circuit breaker, shutting off the ground proximity warning system. It would remain off for the rest of the flight.

Flight 764 now entered the fog, and the lights of the runway became almost impossible to discern. “Tell him to turn the runway lights up,” said Rogers.

“Would you turn up the runway lights please?” Tobias said to the controller over the radio.

The controller turned up the intensity of the runway lights, but it wasn’t enough. “Tell ’em to put the runway lights bright,” said Rogers.

“Please put the runway lights bright,” Tobias repeated over the radio.

“Right on,” said the tower.

As the plane continued to descend through the fog, Flight Engineer Rose called out, “Three hundred feet,” followed seconds later by “two hundred feet.”

“Okay, MDA,” said Rogers. “I’ll level it out right here.” The minimum descent altitude (MDA) for the ILS approach was actually 260 feet (and 560 feet for the VOR/DME approach). They were not supposed to go lower than this without being able to see the runway. But Rogers had pushed it down to 200 feet to try to get a better view through the fog.

“One fifty,” Rose called out as Rogers began to level the plane.

Suddenly, a stand of huge tropical trees loomed up out of the darkness. “Pull up!” Rose shouted.

Rogers pulled back on the controls and pushed the throttles forward to climb away, but it was too late. At a height of 82 feet above the ground, engine two slammed into a tree located 300 meters from the runway threshold. A split second later, the outboard section of the right wing hit another tree and sheared off, plunging the plane into an uncontrollable roll to the right. As Captain Rogers tried to pull his crippled plane out of danger, the stall warning activated, filling the cockpit with the terrifying clack-clack-clack of the stick shaker. “Pull up!” Rose shouted again. But it was no use. “That’s it, I’m dead,” he said. And then the cockpit voice recorder lost power.

Surinam Airways flight 764 rolled inverted and crashed upside down into the forest just meters from the runway, where it broke apart and burst into flames. A few passengers were thrown from the plane still strapped into their seats, but almost everyone either died from the brutal impact or from the massive explosion which followed. As emergency crews rushed to the scene of the crash, they found a young boy, miraculously uninjured, wandering dazed and confused near the plane. A few more survivors followed: 15 people, almost all of them suffering from severe injuries, were found alive near the edge of the wreckage field, where they had been thrown clear of the fire. Some portion of them died in hospital over the subsequent hours, but the exact numbers are unclear: of the 187 people on board, most sources say eleven survived, but the official accident report lists just nine.

Regardless of whether the death toll was 176 or 178, the scale of the disaster was beyond anything the people of Suriname could have ever imagined. In a nation of just 400,000 people, no one was more than one or two degrees of separation from one of the victims. To make matters worse, among the dead were 15 of the 18 Colourful XI football players (although the starting players weren’t on the plane), along with Suriname’s Army Chief of Staff, the Army Chief of Operations, and a former commander of the Air Force. The crash was not only the worst peacetime disaster ever to befall Suriname, but also the deadliest ever plane crash in South America (a title it would hold until 2007). As the entire country clamored for answers, the government of Suriname appointed a special commission of inquiry to uncover the cause of the disaster and issue recommendations to make sure such a tragedy could never happen again.

The investigation into the crash was made more difficult because the DC-8’s antiquated flight recorder only recorded six parameters, and the FDR’s altitude registration was faulty, so it really only recorded five. Nevertheless, by correlating the pilots’ statements with the various alarms and the other flight data, investigators were able to determine the rough profile of flight 764’s ill-fated approach. Despite the pilots’ belief that they were too high, all indications suggested that they were actually too low. Furthermore, a flight test undertaken just days after the crash showed that the glide slope, although officially out of service, was functioning normally. (The localizer was found to be unreliable, but this had no effect on the accident.) The crash occurred not because the out-of-service ILS was faulty, but because the pilots believed that it was. When they saw the lights of the runway refracting through the fog layer, they thought that they were closer to the runway than they actually were, and consequently descended below the glide slope; when the aircraft attempted to inform them of this deviation, they believed their eyes over an instrument landing system that they knew was not reliable.

Unfortunately, their eyes were wrong and their instruments were right. Believing that they would emerge from the fog over the runway threshold, the crew pushed onward below the minimum descent altitude despite no longer being able to see the runway. In fact, they were still over the forest short of the airport. By the time Captain Rogers concluded that the runway could not be seen and that they would need to level off, they no longer had enough altitude left to arrest their descent before hitting the treetops.

Investigators noted that throughout most of the approach to the airport, the crew was actually flying a visual approach, not an ILS approach. Because they were continuously too low, they never actually captured the glide slope, and Captain Rogers mostly flew the airplane by eye based on where he thought the runway was located. In effect, they were flying three different approaches simultaneously: they were cleared for a VOR/DME approach, they believed they were flying an ILS approach, and in reality they were flying a visual approach. All of these approaches were against regulations, since the visibility was too low for a VOR/DME or visual approach, and the ILS was out of service. The correct course of action would have been to hold until the weather improved or divert to another airport.

This raised another equally important question: why would a crew with more than 52,000 combined flight hours decide to do something so blatantly reckless as to fly an ILS approach using an ILS they knew was unserviceable? In all likelihood this was not the first time these pilots had resorted to illegal measures to get their plane on the ground. To understand why a trained crew would act this way, investigators looked into the history of the pilots, where they uncovered a story that almost defied belief.

The first red flag was the fact that Captain Will Rogers was considerably over the 60-year age limit for commercial pilots, per regulations in both the US and Suriname. (Flight Engineer Warren Rose was also over 60, but this was allowed for flight engineers.) Looking into Captain Rogers’ training history, they found that his most recent proficiency check, conducted in April 1989, wasn’t on a DC-8 at all, but on a five-seat Grumman Cougar GA-7 light aircraft. The proficiency check was carried out by a Maryland-based company called Flying Tigers, Inc., which not-so-coincidentally sounded very similar to the name of the well-known cargo and charter carrier Flying Tiger Line, which operated DC-8s and was commonly referred to as the “Flying Tigers.” Captain Rogers had apparently passed off this proficiency check as being on a DC-8 by tricking his employers into thinking he got it from Flying Tiger Line.

Interviews with personnel at Rogers’ employer, Air Crew International, revealed that the company did not arrange recurrent training and proficiency checks for its pilots; instead, it expected the pilots to fulfill these requirements on their own. Rogers likely saved time and effort by getting a proficiency check on a Grumman Cougar rather than a DC-8, and neither Air Crew International nor Surinam Airways ever looked at the fine print.

Next, investigators looked at First Officer Glyn Tobias. He too had not received a proficiency check on the DC-8 within the required timeframe, but that was perhaps the least surprising thing about him. The most shocking thing about Tobias was that he was living under an assumed identity: Glyn Tobias wasn’t his real name, and he wasn’t actually born in Texas in 1954. Investigators found that he had previously lived in the United Kingdom under two different names with two different birthdates (1945 and 1946) and two different places of birth (Newport, South Wales; and Coventry, England). The commission was unable to determine which of his various identities was the original. To make matters worse, Tobias’ FAA pilot certificate had been approved on the basis of a UK pilot certificate with the identification number 84846, but when the Surinamese investigators inquired to the UK’s Civil Aviation Authority about this certificate, the CAA reported that the certificate never existed! After somehow getting a US pilot certificate on the basis of fraudulent foreign credentials, he flew in America for some time before being involved in an accident in Wichita Falls, Texas, at which point his FAA certificate was revoked. Following this accident, he got a job with Air Crew International and started flying on contract for Suriname Airways, despite no longer possessing the requisite qualifications (which he was never supposed to have received in the first place).

Investigators soon discovered that Captain Rogers was similarly underqualified. Rogers failed his initial Air Transport Pilot exam in 1970 due to poor adherence to ILS procedures and poor judgment. He passed on his second attempt 18 days later. Then in 1973, he failed his first two attempts to get his DC-8 type rating due to unsatisfactory performance in pre-flight checks, simulated engine failure, takeoff, holding, instrument approaches, and steep turns. He passed on his third attempt. And finally, in 1985 he failed a type rating exam for the 747 due to poor performance in holding, missed approaches, and landing; he passed on the second attempt 9 days later. This poor performance had translated into real world results: during his career, he had been involved in three serious incidents while flying commercial airliners. One time in Miami, he ignored warnings from airport officials and powered the engines up to full RPM while right next to the terminal. Another time in Belem, Brazil he went off the runway and got stuck in the mud after turning too sharply while taxiing. And just four months before the crash, he landed hard during a thunderstorm in Lisbon, Portugal, damaging both the landing gear and the runway. After this incident, he was banned from flying for Surinam Airways. But within weeks, he was right back at it! Surinam Airways’ logistics department noticed this discrepancy and forwarded it to the department director, who took no action whatsoever. It was also discovered that the Flight Operations Manager was aware of the issue, but he too did nothing. In general, the managers did not know who was flying for Surinam Airways at any given time, because the crews were assigned by Air Crew International upon request using an intermediary. So when Air Crew International kept assigning Captain Rogers to fly Surinam Airways flights despite the ban, the aforementioned managers wouldn’t know unless they explicitly asked.

Interviews at Air Crew International also revealed why Rogers and Rose were still flying despite being over 60 years old: company managers thought that they could lease over-age pilots to foreign carriers who flew to the US under part 129 of the federal aviation regulations, which described operating requirements for foreign airlines flying in the United States. This assumption was false and had no basis in reality. In all probability this was a hastily formulated excuse to cover for Air Crew International’s practice of knowingly leasing over-age or unqualified pilots to foreign carriers like Surinam Airways that weren’t exercising sufficient oversight to catch on to the scam.

These findings raised serious red flags at the US National Transportation Safety Board because all this negligence took place in America, where regulations were supposed to be tight and safety standards high. Upon further investigation, the NTSB found that Air Crew International was just one of many companies, nearly all based in Miami, leasing unqualified pilots to foreign carriers operating in the US under part 129. This shadow industry of “pilot brokers” had sprung up organically and received no oversight whatsoever from the FAA. Furthermore, the effects of this industry were usually not discovered because the FAA had a policy of not conducting ramp inspections of foreign aircraft when they stopped at US airports, apparently to prevent retaliation against US carriers operating abroad. Among the items typically reviewed in such inspections are pilot certificates, which would easily reveal the illegal practices. The case of this particular flight crew was especially frustrating because the DC-8 they were flying was registered in the United States, which meant it was fully within the FAA’s rights to inspect the plane and its crew any time it made its scheduled stops in Miami. In practice, however, the use of a US-registered airplane and crew on a Surinamese airline meant that neither country adequately monitored its day-to-day operations.

In its final report, the Commission of Inquiry recommended that Surinam Airways reform its flight operations department; that the government exercise greater oversight over the airline; and that Suriname put together a comprehensive disaster response plan to respond to the next big emergency, no matter what form it takes. Meanwhile in the US, the NTSB had some pointed recommendations for the FAA. The agency asked that the FAA conduct periodic ramp inspections of foreign air carriers operating in the US; that foreign airlines operating under part 129 be required to provide the FAA with pilot certification information including the pilots’ names and dates of birth; and that the FAA develop rules governing the so-called “pilot broker” companies. In 1993, the FAA began requiring part 129 foreign operators to supply dates of birth for all their crews in order to crack down on the leasing of over-age pilots. However, the FAA initially pushed back against the recommendation to exercise other forms of oversight of foreign carriers, arguing that under international rules it was the responsibility of the airlines’ states of registration to ensure that their crews are properly qualified. In an archived letter, the NTSB replied: “Foreign airline operators have been found to rely upon suitability determinations by U.S. firms that locate, advertise for, and supply flight personnel. As illustrated in the June 7, 1989, accident involving a Surinam Airways DC-8, the U.S. firm that provided the pilots had no requirement to determine an individual’s suitability, although the pilots were presented to the foreign airlines as ‘suitable.’” In 1994, the FAA finally changed its stance and agreed with this argument; today, foreign carriers operating in the US under part 129 must prove to the FAA that all their pilots are properly qualified. Any US company that tries to shop around unqualified pilots to part 129 carriers will soon find that the market has disappeared.

Today, the crash of flight 764 is not well remembered globally. But in Suriname, the disaster caused a sort of national PTSD. Everyone knows about the crash; few have any desire to talk about it. A surreal memorial sits at the crash site: a row of monuments surrounded by the half-buried remains of the plane, which was interred where it came to rest and periodically spits pieces of withered metal up onto the surface. But while Suriname continues to remember the crash because of the tragic loss of life, in the United States, the crash has led to several underappreciated regulatory changes which have had a tangible impact on the safety of airlines around the world. While it’s never a completely safe bet for foreign carriers to assume that “American” equals “quality” when it comes to flight crews, it’s a safer bet than it used to be.

______________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit!

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read over 170 similar articles.

You can also support me on Patreon!