Fly-By-Night Freight: The crash of Aerosucre flight 157

On the 20th of December 2016, a Colombian cargo plane overran the runway while attempting to take off from the city of Puerto Carreño. In an event captured on video, the Boeing 727 plowed through the airport perimeter fence, nearly struck several planespotters, clipped a tree and a sentry box, then finally lurched into the air. As the stunned planespotters continued to watch with cameras rolling, the pilots fought to regain control of their badly damaged jet, which had lost its number three engine, part of its landing gear, and all of its hydraulic systems. The 727 struggled on for another two minutes, slowly losing control and losing altitude, until it rolled abruptly to the right and crashed into the ground, killing five of the six crewmembers on board.

An investigation by Colombian authorities found failures at every level. The airport at Puerto Carreño was too small for the Boeing 727, and the airline hadn’t received approval to operate it there. Modifications to the plane weren’t reflected in its documentation. And the pilots made a series of preventable errors, starting with an incorrect takeoff technique and ending when they failed to activate a critical backup system that could have saved their plane. Linking all the disparate factors was an airline with a staggering history of violations and deadly crashes stretching back nearly 50 years.

In a country like Colombia, where geography itself hampers the construction of a robust road network and rural areas have historically been controlled by a patchwork of anti-government and criminal elements, air cargo has long been a vital link ensuring that the inhabitants of far-flung towns and cities can enjoy the fruits of the modern global economy. One of Colombia’s longest-running cargo airlines is Aerosucre, a relatively small but well-established carrier that has found success through its willingness to fly anywhere and carry anything.

Aerosucre has always operated old second-hand aircraft, and for the last 30 years, the workhorse of its fleet has been the three-engine Boeing 727. Aerosucre has gone through a relatively large number of 727s over the years, only some of which made it to retirement; records indicated that by 2016, no less than three Aerosucre 727s had been destroyed or damaged beyond repair in various accidents. This didn’t seem do much harm to the company’s financial status, as they simply bought another one every time one crashed.

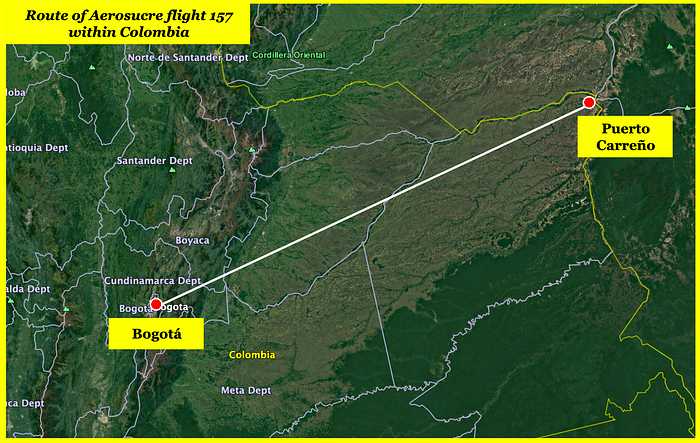

One of the 727s in Aerosucre’s fleet in 2016 was HK-4544, an aging example built in 1975 and purchased from an American owner in 2007. On the 20th of December 2016, this aircraft was scheduled to fly a routine cargo run from the capital, Bogotá, to the town of Puerto Carreño on the border with Venezuela and back again the same day. An isolated town of around 20,000 inhabitants, Puerto Carreño is served by Germán Olano Airport, whose single runway usually plays host to small aircraft and regional jets. Aerosucre’s 727s were the only full-sized airliners to regularly visit the field.

In command of the round trip flight were three pilots: 58-year-old Captain Jaime Castillo, 39-year-old First Officer Mauricio Guzmán, and 72-year-old Flight Engineer Pedro Duarte. In Bogotá, the pilots and their loadmaster oversaw the loading of around 20,400 pounds of perishable food items bound for Puerto Carreño, which upon landing would be exchanged for at least 43,700 pounds of an unspecified cargo for the return journey to Bogotá, designated flight 157.

HK-4544 arrived in Puerto Carreño without incident at 14:48, exchanged its cargo, and was ready to depart again sometime after 17:00. Anticipating the departure of the 727, a number of planespotters headed out to the runway on bicycles to film the takeoff.

By the time it departed the parking area, six people had boarded the plane: the three pilots, the loadmaster, a mechanic, and one apparently unauthorized passenger who wasn’t listed on the flight plan. Furthermore, although the cargo manifest listed 43,700 pounds of cargo, evidence indicates that there may have been up to 2,500 additional pounds of undeclared goods, which made the plane 1,300 pounds over the maximum allowable takeoff weight for Germán Olano Airport’s 1,800-meter runway. The pilots were well aware of their real weight, but relatively minor load exceedances such as this were a fact of life at Aerosucre.

From there, the errors only began to compound. According to the latest weather report, the wind was blowing out of 10 degrees with a speed of 8 knots. But the pilots hadn’t requested the weather from the local meteorological office, and they couldn’t ask ATC because Germán Olano Airport became an uncontrolled field when the controller went home at 15:00. Instead, Captain Castillo simply decided that the wind wasn’t strong enough to worry about, and chose to take off on runway 25 because it was more convenient. This resulted in a four-knot tailwind component for takeoff, which was why all the planes ahead of them had been taking off in the other direction, on runway 07.

Before taxiing to the runway, the pilots briefed their takeoff plan, including the speed they would use for liftoff, which they selected from a table of speeds in the flight manual. But here there was yet another problem: the table in the manual didn’t correspond to the actual configuration of the airplane. In 2015, Aerosucre modified HK-4544 by installing a droop system, which allowed the flaps to extend to 30 degrees for takeoff (previously they were limited to 25 degrees). By increasing the maximum lift that the flaps were capable of generating, the droop system helped improve takeoff performance and fuel efficiency. But an important step in the modification program — a step which Aerosucre never completed — was to update the speed tables in the flight manual to include speeds for the newly available flaps 30 takeoff. On flight 157, the pilots planned to take off with the flaps set to 30 degrees, but because the table didn’t provide any benchmark speeds for this setting, they used the values for a flaps 25 takeoff instead, concluding that with a gross weight of 166,000 pounds — including the undeclared excess weight — they should rotate to lift off the runway at a speed of 127 knots. In fact, this was faster than necessary; thanks to the improved lift provided by the flaps 30 setting, it was possible to lift off at only 122 knots, thereby shortening the takeoff roll. But without the updated tables, the pilots had no way of knowing this.

At 17:18, the pilots lined up their plane with runway 25, and Aerosucre flight 157 began its takeoff roll. Even with the tailwind, the excess weight, and the unnecessarily high rotation speed, they should have just barely made it. But as the plane accelerated down the runway, Captain Castillo made one last error that sealed their fate. When First Officer Guzmán called out, “V1, rotate,” Castillo pulled back on his control column too slowly. Boeing recommends that a pilot rotate for takeoff at a rate of about two to three degrees per second, but Castillo’s half-hearted effort only amounted to one degree per second, extending their takeoff run even more.

On the airport perimeter road, the group of planespotters, clustered around their bicycles, stood with cameras rolling as the plane hurtled towards them. But as the 727 drew closer and closer without lifting off, they started to get out of the way, and just in time, too. The jet, now moving at 140 knots, rumbled off the end of the runway with its nose in the air, throwing up dust as it roared over the grass. It finally started to become airborne at the last possible second, but it was too late. As planespotters scrambled for cover, the plane plowed over the meter-high airport perimeter fence, crossed the road in a great cloud of dust, and struck a tree and a military sentry box with a deafening crash.

Under its own momentum, the badly damaged 727 continued into the air, climbing away from the airport with dust trailing behind it. On board the plane, chaos reigned. The impact with the tree and the sentry box ripped off the right main landing gear, damaged both of the plane’s hydraulic systems, tore off one of the right trailing edge flaps, and threw debris into the number three engine, causing it to fail.

“Engine three went, bro!” Captain Castillo said, watching its power spiral down on his engine indication panel.

“Is engine three gone?” First Officer Guzmán asked.

“Yes, three!”

With one of the right wing flaps missing and the right engine dead, Captain Castillo needed to steer left with the rudder in order to counter the excess drag and loss of thrust on that side. But the hydraulic lines had been severed when the right landing gear broke away, and he was starting to lose control authority.

Guzmán attempted to raise the landing gear, but the indication showed that the right gear didn’t come up. He had no idea that it had departed the aircraft entirely. “Right gear!” he said.

“Turn off number three!” Castillo ordered.

“I lost hydraulic [system] A!” shouted Flight Engineer Duarte.

“The right is gone!” said Castillo.

“Let’s lower it,” said Guzmán.

“Lower the gear, lower the gear!” said Castillo.

“Lower the gear!” Duarte echoed.

“Lowering the gear,” Guzmán announced.

The plane reached a height of 790 feet, but due to an increasing right bank and the partial loss of thrust, it began to descend. “CAUTION, TERRAIN,” said the ground proximity warning system. “CAUTION, TERRAIN. CAUTION, TERRAIN. CAUTION, TERRAIN.”

“Do I put power on it?” Guzmán asked.

“Yes!” said Castillo. “Oops, we are entering a stall, oy!”

“No, no, capi, no!” said Guzmán.

“TERRAIN,” said the GPWS.

“Let’s fly it gently,” Guzmán added.

“Gently,” Castillo repeated.

“TERRAIN, TERRAIN,” the GPWS blared again. “TERRAIN, TERRAIN!”

“Engine three, engine three!” Captain Castillo repeated.

“Dump fuel,” suggested Flight Engineer Duarte, in an attempt to reduce their weight enough to stay in the air. “Dump fuel!”

“Yes, dump the fuel!” said Castillo.

“Dump it,” Guzmán agreed.

“Dumping fuel,” Duarte announced, opening the fuel jettison switches.

“Capi!”

“Wait!”

“TERRAIN, TERRAIN!”

“No no no no!” said Castillo. “The plane is not accelerating for me!”

“TERRAIN, TERRAIN!”

“Raise the gear!” Castillo ordered.

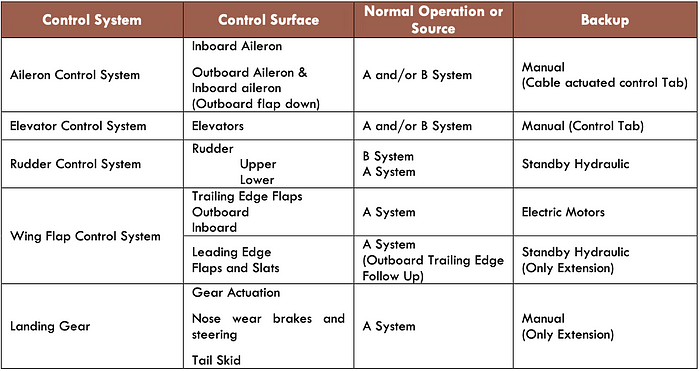

By now all the hydraulic fluid had drained out of both main hydraulic systems. The elevators and ailerons could still be used because they were cable-operated, but the rudder could only be controlled hydraulically. In order to regain control of the rudder, the flight engineer needed to flip the “standby rudder switch” to activate the standby hydraulic system, an independent set of hydraulic lines which could provide backup pressure to the rudder and other systems that could not be operated mechanically. This was item number three on the “loss of hydraulic pressure” emergency checklist, but nobody had pulled it out. Instead, Captain Castillo kept trying to turn left with the ailerons to overcome the right roll, but the roll was more powerful than the ailerons. He needed to bring the rudder online to regain control, but everyone seemed to be focused elsewhere. The 727 began a wide, descending turn to the right over the bush outside Puerto Carreño as planespotters continued to film from a distance.

Meanwhile on board, the pilots kept fighting to control the plane.

“Raise the gear! Raise the gear!” Castillo ordered again. But without hydraulic power, it was impossible to raise the landing gear once it was lowered.

“Capi, capi!” First Officer Guzmán exclaimed.

“Raise the gear!” Castillo said again. Nothing happened. “No, no reaction!”

“No!”

“Wait, lower it!”

The stick shaker activated, warning of an impending stall.

“No!”

“Lower the gear!”

“It’s dumping?”

“Yes, the fuel is dumping!”

But they were out of time, and out of altitude. At just a few dozen feet above the ground, the plane slowed down to the point that Captain Castillo’s control inputs could no longer prevent the right bank from escalating into a rapid roll. The plane heeled over 58 degrees to the right and dived into the ground, throwing up a massive explosion visible for miles in every direction. The plane cartwheeled and broke into four large sections, which tumbled through the bush for over 400 meters before coming to rest in a field.

The crash instantly killed four of the six people on board, but as witnesses rushed to the scene to help, they found that the mechanic had survived the crash and dragged himself from the wreckage despite serious injuries. Another crewmember was found alive and rushed to hospital as well, but he soon died, leaving the mechanic as the only survivor. Although their harrowing video seemingly indicated otherwise, none of the planespotters congregated at the end of the runway was injured, despite their dramatic brush with death.

Within hours, the Accident Investigation Group of Colombia, or GRIAA, launched an investigation into the cause of the crash. It was not the first time they would be heading to the scene of an accident involving Aerosucre: the airline had been involved in 13 previous crashes and serious incidents, several of them fatal, since its founding in 1969.

Aerosucre was already known for its poor safety standards and questionable business practices. In the mid-1990s, a large amount of cocaine paste was seized from aboard an Aerosucre cargo plane, where it had been hidden inside a shipment of fish. In addition to drugs, the airline had a history of carrying illegal passengers, a widespread problem in remote regions where legitimate commercial flights can be prohibitively expensive. This problem was highlighted when an Aerosucre cargo plane with 17 passengers aboard crashed short of the runway, killing two, in 1991. One of the survivors told El Tiempo that passengers had been forced to lie on the floor during the flight because the plane didn’t have any seats. And then there was Aerosucre’s history of losing Boeing 727s, including their most serious accident in 2006, in which all six crew aboard a 727 were lost when the plane descended too low on approach and hit a 46-meter television antenna. But despite its abysmal safety record, in 2013 the Colombian government gave the airline’s owner a medal for outstanding service to the country, underscoring a dilemma common in poor countries: sometimes the job either gets done unsafely, or not at all.

Investigators therefore were not overly surprised when they discovered that Germán Olano Airport was not authorized for Boeing 727 operations, nor had Aerosucre received permission from the Aeronautical Authority of Colombia to fly 727s there. The pavement used at the airport was not rated to withstand the weight of a 727, and the runway was narrower than the minimum width permitted for 727 operations. Nevertheless, the Aeronautical Authority’s Aerodrome Reporting Office responsible for approving the flight plans for Aerosucre’s flights to and from Puerto Carreño had been rubber stamping the documents since at least 2009 without any apparent knowledge that the flights were illegal. The airline itself was supposed to carry out a risk analysis before starting operations to a new airport, but in all likelihood, the company simply said “we want to fly to this airport,” someone checked that the runway was long enough, a little bit of paperwork was filled out, and away they went.

But even if the airport didn’t meet the requirements for 727 operations, it should have been physically possible to get a 727 off the ground on its 1,800-meter runway, and in fact Aerosucre had done so successfully for several years. Investigators were able to find a number of factors which contributed to this particular flight’s failure to do so.

The first problem was the excess weight of the plane. Aerosucre frequently flew overweight planes; in fact, it was grounded for 24 days in 2005 after the Aeronautical Authority discovered chronic overloading (although this grounding clearly did not end the practice). The pilots were aware that their plane weighed 166,000 pounds, 1,300 more than the maximum takeoff weight for Germán Olano Airport under the conditions, so they factored this into their takeoff distance calculations. But the extra distance required due to the extra weight reduced their margin for error — and there would be errors aplenty.

The first error was that Aerosucre hadn’t updated their speed tables for a flaps 30 takeoff after they installed the droop system; this caused the crew to pick a rotation speed designed for a flaps 25 takeoff, when they could have used a speed which was five knots lower. Waiting until 127 knots to rotate added 103 meters to the takeoff distance.

The second error was the selection of runway 25 instead of runway 07, which resulted in the plane taking off with a four-knot tailwind component. The pilots made this choice due to both a lack of information and a lack of curiosity, since wind information could have been acquired — if not from the meteorological office, then from a wind sock that should have been plainly visible as they taxied to the runway. But as far as the investigators could tell, the pilots just didn’t care about a relatively light tailwind. That was too bad, since it added 146 meters to the takeoff distance.

Finally, the third error was the captain’s unacceptably slow rotation technique, which forced the plane to stay on the ground longer than necessary, and which caused it to climb at a shallower angle. By rotating at one degree per second instead of two to three, he added 134 meters to the takeoff distance.

Like death by a thousand pinpricks, all these little increases added up until flight 157’s takeoff distance exceeded the length of the available runway.

After that, the sentry box and the tree — which were closer to the runway threshold than regulations permitted — turned what could have been a close call into a serious emergency. But even with the severe damage caused by the impact with the obstacles, the pilots could have saved the plane simply by following the emergency checklist for a hydraulic failure. Flight Engineer Duarte was aware that they were losing hydraulic power, and he said as much to the pilots, but for some reason no one ever pulled out the emergency checklist and took the necessary action. If someone had simply moved the standby rudder switch to “on,” hydraulic power to the rudder would have been restored, and Captain Castillo would have regained enough control authority to stop the right roll, level off, and circle back for an emergency landing. Why the crew never pulled out the checklist cannot be known for sure, but their failure to do so is suggestive of insufficient training which left them unprepared to react logically in a highly stressful emergency situation.

After taking into account all the contributing factors, it cannot really be said that the pilots were the cause of the crash, although they certainly made mistakes. Rather, the accident was the inevitable result of an operating culture at Aerosucre where risks were ignored and deviations were normalized; who was actually at the controls that day was not the deciding factor. Aerosucre had uncritically accepted the risks of operating an overweight 727 without up-to-date speed tables and with poorly trained pilots out of an airport that left little room for error. They had almost paid the price before: in a video from October 2015 (left), an Aerosucre Boeing 727 can be seen almost crashing during a takeoff from the very same runway where flight 157 met its doom. An airline with a properly functioning safety management system would have flagged this incident, found the causes, and implemented a solution so it wouldn’t happen again. Lives would have been saved. But instead, Aerosucre just kept flying at the limit until they found it the hard way.

In their final report, the GRIAA criticized the crew for their casual attitude toward proper procedures; criticized the airline for habitually ignoring regulations; and criticized the Aeronautical Authority for failing to notice (or, if you have a more cynical outlook, for being aware but doing nothing to stop them). But despite these findings, and the GRIAA’s recommendations intended to prevent a recurrence, Aerosucre is still flying today, and it’s not obvious why this crash, as opposed to all the others, would lead to a significant change in mindset. As far as can be determined without going and checking in person, Aerosucre is no longer flying Boeing 727s to Germán Olano Airport, but the conditions which made the airline decide flying there was a good idea remain in place. And if they lose another plane — which, if they keep operating this way, they will — no one will be surprised.

_____________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit!

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 190 similar articles.

You can also support me on Patreon.