Touch-and-Go Tragedy: The crash of Air Canada flight 621

On the 5th of July 1970, an Air Canada DC-8 plunged burning from the sky over Brampton, Ontario, leaving behind little more than a smoking crater in a field. The crash claimed the lives of 109 people, a toll which remains the worst in Air Canada’s history, even after more than 50 years. The sequence of events which brought it down was unique, but almost banally simple: the plane landed hard, damaging a fuel tank, then lifted off again with its right wing on fire. Before it could circle around to land again, the wing failed, and the plane, crippled beyond all hope, spiraled horribly to the ground. As it turned out, everything began with a single, ill-timed mistake: the First Officer, while attempting to arm the ground spoilers to deploy after landing, accidentally deployed them in flight instead, causing the plane to lose lift and crash to the ground. In a fit of apologia, the First Officer appeared to blame himself for the unfortunate error, but was he really at fault? The investigation would reveal that the answer was not quite so simple, as the board of inquiry discovered a substantial design flaw in the DC-8 which the manufacturer had not only overlooked, but seemingly hid from its customers.

◊◊◊

On April 29th, 1970, Canadian flag carrier Air Canada took delivery of a brand new, four-engine McDonnell Douglas DC-8–60 series airliner, known by its registration number CF-TIW. An upgrade from the smaller DC-8–50 series, which Air Canada had operated since 1968, the 60-series featured a stretched passenger cabin that briefly made it the highest capacity airliner on the market, until it was overtaken by the Boeing 747. Air Canada purchased 14 of the new model, which arrived throughout 1970 and would ultimately remain in service until 1986 — except for the ill-fated CF-TIW.

The aforementioned aircraft met its end only about two months after it entered service, while operating the regularly scheduled flight 621 from Montreal, Quebec, to Los Angeles, California, with a stopover in Toronto. The weather that day — the 5th of July — was perfect for flying, with only a few broken clouds, minimal wind, and no reports of turbulence. The 100 passengers who boarded the DC-8 could have expected a smooth ride, as did the crew, consisting of six flight attendants and three pilots. In command was 50-year-old Captain Peter Hamilton, a veteran pilot both by his 20,000 flight hours and by his time in the Royal Canadian Air Force, with which he saw action in the Second World War. Joining him was 40-year-old First Officer Donald Rowland, who had about 9,000 hours and was also a former RCAF airman, although his career since then had not been without hiccups: two years earlier, in 1968, he had been told that he had no chance of upgrading to Captain anytime soon. And lastly, there was 28-year-old Flight Engineer — officially Second Officer — H. Gordon Hill, who was much less experienced than either pilot, with only about 1,200 hours and a flying career stretching back no farther than 1965.

At 7:17 a.m. local time, CF-TIW departed Montreal on flight 621, bound for the first stop of the day in Toronto, less than an hour to the southwest. The flight proceeded normally through the top of the descent, where the cockpit voice recorder picked up the pilots engaged in a friendly conversation.

“Monday afternoon, I didn’t wake up until half past one in the afternoon,” Captain Hamilton said. “Took a long walk down around the city. I wound up in a pub I haven’t been in since 1944…”

The conversation continued for some time, as the pilots were clearly in good spirits. Air Traffic Control cleared them down to 8,000 feet in anticipation of an instrument approach to runway 32, and First Officer Rowland replied with a polite readback.

Minutes later, a stewardess entered the cockpit with a report: “Captain,” she said, “A passenger, er — he works on the ramp, he says that [in] Montreal, someone forgot to close a panel at the back.”

“Oh! On which side?” said Captain Hamilton.

“On that side,” said the stewardess, pointing to the left.

“Number one engine?” Hamilton asked.

“Yeah.”

“Okay, it’s probably torn off by now,” said Hamilton.

“Hey, (…) we’re going to get a new airplane in Toronto,” First Officer Rowland commented. If the maintenance access panel was missing, that wasn’t a safety concern, but it did mean that CF-TIW would need to be grounded for repairs, so they would have to change to a new plane for the journey onward from Toronto to Los Angeles — a minor inconvenience at most, but probably the worst thing the pilots expected to happen that day. First Officer Rowland reported the news to company operations, and that was the end of the matter.

In 1970, pilots were not yet required to keep conversations on topic below 10,000 feet, and the crew of flight 621 continued to mix operational and personal discussions as they neared Toronto International Airport. The cockpit voice recorder captured a discussion of pay, followed by vectors from Toronto approach control, then some idle whistling, and finally the in-range check, as the pilots configured their plane for the approach.

Coming in low over the city of Toronto, First Officer Rowland commented, “Nice day.”

“Beautiful,” Hamilton agreed.

“Apartments, see them there,” Rowland said, pointing at a new lakefront development.

“Oh, the white ones there?” Hamilton asked.

“Yeah.”

“Oh yeah.”

“It looks over the (…),” Rowland explained. “It’s quite a good view out over the lake there.”

“The housing in Toronto is out of this world expensive, yeah,” the young Flight Engineer Hill commented. (Some things indeed never change…)

“Yeah, expensive alright,” said Rowland. “Yeah, a lot of people must have made a lot of money.”

“Yeah, I’ll say,” said Hamilton.

Moments later, ATC cleared them for the approach, and the pilots made the turn onto the base leg, one turn away from final. Simultaneously, with the plane nearing 1,000 feet, Captain Hamilton called for the Before Landing checklist. First Officer Rowland called out, “Check three green, four pressures,” referring to the brakes and hydraulic pressure, followed by, “spoilers on the flare.”

“Okay, brakes three green, four pressures, spoilers on the flare,” Captain Hamilton read back.

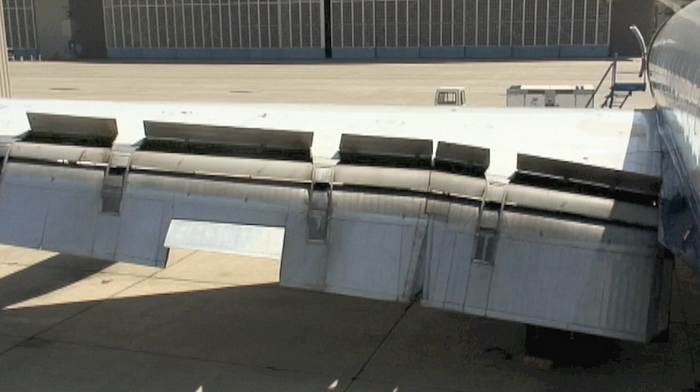

All large aircraft are equipped with spoilers — panels which rise up from the wings to interrupt the airflow and reduce lift. The applications of spoilers include enhancing descent rate without increasing forward airspeed; assisting the ailerons in rolling the plane, when deployed asymmetrically; and finally, reducing lift after touchdown, so that the weight of the airplane settles onto the wheels, increasing the effectiveness of the brakes. The DC-8 had 10 separate spoiler panels, five on each wing, of which the outboard three (or “flight spoilers”) were used both in flight and on the ground, while the inboard two (or “ground spoilers”) were to be deployed only after touching the ground, and never in flight.

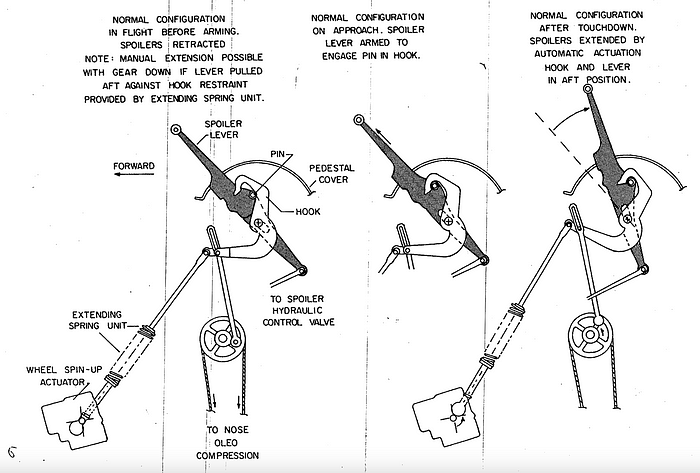

On the DC-8, the spoilers were used only for roll assistance in flight and braking assistance on the ground. While most airliners have spoilers which also act as a speed brake during descent, the DC-8 accomplished this function through the use of in-flight reverse thrust on its inboard engines instead. When assisting in roll, deployment of the flight spoilers was automatic on the “down” wing, but when providing braking assistance on the ground, the spoilers could be deployed either automatically or manually. To arm the ground spoilers, a pilot could pull the spoiler lever upward, engaging a mechanical interlock that would cause the spoilers to deploy automatically once the wheels touched the ground. Alternatively, should the need arise, the ground spoilers could be deployed manually by pulling the spoiler lever backward to the “EXTEND” detent, rather than upward.

At Air Canada, the standard procedure was to arm the spoilers during the before landing checklist at a height of at least 1,000 feet above the ground. Manual deployment was not envisioned. But some Air Canada pilots didn’t like flying the last 1,000 feet with the spoilers armed due to the perceived risk of an uncommanded deployment, and as a result several unapproved, alternate procedures had arisen. The first of these was to avoid arming the spoilers at all, deploying them manually after touchdown instead, a method of which Captain Hamilton was a longtime adherent. On the other hand, some Air Canada pilots had taken to arming the spoilers for automatic deployment not at 1,000 feet during the Before Landing checklist, but during the “flare,” where the flying pilot pulls the nose up in preparation for imminent touchdown. This allowed use of the automatic spoilers, as Air Canada wanted, while also avoiding the perceived risk of flying with the spoilers armed for any significant period of time.

It is unclear which method First Officer Rowland preferred, but what is known is that sometime prior to flight 621, Rowland and Hamilton had reached an agreement regarding the methods of spoiler deployment to be used when flying together. Apparently, when Hamilton was flying, he asked that Rowland deploy the spoilers manually after touchdown, as he preferred. On the other hand, when Rowland was flying, Hamilton promised that he would arm the spoilers “on the flare,” as described above.

Therefore, instead of arming the spoilers during the Before Landing checklist, the pilots knew that they would arm or deploy them later — but which method should they use? Initially, First Officer Rowland instinctively said “on the flare,” and Captain Hamilton read this back. But moments later, Rowland apparently remembered that when Hamilton was flying, as he was today, he preferred the spoilers to be deployed manually, so he said, “Or — on the ground.”

“Alright, give them to me on the flare,” Captain Hamilton replied. “I’ve given up. I’m tired of fighting it.”

Rowland chuckled. Apparently Hamilton had let him win, voiding their old compromise.

“Fuel panel set,” Flight Engineer Hill called out.

“Thank you,” said Hamilton. “Thirty five flap.”

“Thirty five,” said Rowland, extending the flaps to 35 degrees.

Approach control cleared them for the turn to intercept the instrument landing system, then handed them off to the tower for landing clearance. Rowland acknowledged, switched to the tower frequency, and reported their position. The tower replied that flight 621 was number one for landing, with two Boeing 727s taking off ahead of it.

“Landing flap,” Hamilton called out.

“One twenty-nine,” said Rowland, calling out their airspeed.

Presumably looking through binoculars, the tower controller confirmed that flight 621 was fully configured for landing. “Six two one, check your gear down,” the controller said.

“Gear down,” Rowland confirmed.

“Spoilers to go and the board’s clear,” said Flight Engineer Hill, announcing the completion of the Before Landing checklist, except for the spoilers.

“Okay, thanks,” said Hamilton, who started whistling.

Hamilton and Rowland then exchanged remarks about a 727 taking off ahead of them with a pall of white smoke in its wake. “He’s leaving a smokescreen for you just to make it a little more challenging,” said Rowland.

“Six two one, Toronto, clear to land on runway three two,” said the tower.

“Six two one,” Rowland acknowledged.

The pilots discussed the approach angle as the runway drew nearer, until at last the DC-8 arrived over the threshold. Hamilton began reducing power and pulling up to flare for touchdown, at which point he called out “Okay” — the signal to arm the spoilers. First Officer Rowland immediately grabbed the spoiler lever to comply.

It was at that point that Rowland made a simple but terrible mistake: accustomed to deploying the spoilers manually when Captain Hamilton was flying, he instinctively moved the spoiler lever back to the “EXTEND” position, instead of lifting the lever to arm the system. Within three tenths of a second, all the spoilers, including the ground spoilers, deployed while the plane was still 60 feet (18 m) above the runway. With the lift from the wings severely reduced, the plane lurched downward, immediately alerting both pilots to Rowland’s mistake.

“Sorry — oh! Sorry Pete!” Rowland exclaimed.

Captain Hamilton quickly pushed the engines up to max power in an attempt to reverse the sudden descent and avoid impacting the ground, and as soon as he did so, a safety system kicked in to automatically retract the spoilers. But it was already too late: less than three seconds later, the DC-8 struck the runway with a vertical speed of about 650 feet per minute. The heavy blow, well in excess of the plane’s structural design limits, bottomed out the suspension on the landing gear, caused the sacrificial bumper pad on the tail to strike the runway, and flexed the right wing so heavily that the force overcame the load-bearing capacity of the number four engine pylon. The number four engine, with its supporting pylon attached, ripped straight off the wing and tumbled ahead down the runway under its own momentum, spraying fire behind it as fuel poured from a sudden breach in the number four alternate fuel tank.

Just as quickly as it touched down, however, the DC-8 rocketed back into the air, having spent less than half a second on the ground.

“Sorry Pete!” First Officer Rowland repeated.

“Okay,” said Captain Hamilton, putting the plane into a steady, controlled climb. He could feel the plane yawing to the right due to the loss of thrust from the number four engine, and he instinctively countered using the rudder. “We’ve lost our power,” he said.

Observing from the tower, the controller saw flight 621 climb away, leaving behind a cloud of dust and debris on runway 32. “Air Canada six twenty one, (…) checks you on the overshoot,” he said, using a now-archaic term for a go-around, “and you can contact departure on one nineteen nine or do you wish to come in for an immediate on five right?”

Believing that the pilots knew the condition of their airplane better than he did, he offered them two solutions: an immediate 270-degree orbit to land on runway 5R, or a longer climb out to run checks before coming back down, in which case they would contact departure/approach control on 119.9 instead of staying with him.

“Oh, we’ll go around, I think we’re alright,” said Captain Hamilton.

“Oh, roger, we’ll go all the way around, thanks,” First Officer Rowland reported.

“Okay, contact departure,” said the tower.

“Roger, one nineteen nine,” said Rowland, reading back the frequency.

“Get the gear up please, Don,” said Hamilton.

Rowland raised the gear, which retracted normally, despite the heavy landing. To the pilots, that must have felt like an indication that their plane, although clearly damaged, could not have landed too heavily — or had it?

“What about the flap?” Rowland asked.

“Flap twenty-five,” Hamilton ordered.

“Number four generator’s gone,” Flight Engineer Hill reported, observing a total loss of electrical power from the generator in engine four.

“Okay, get the cross feed off first though,” said Hamilton. “Will you give approach a call?”

“Toronto approach control, Air Canada six twenty one is overshooting on thirty two,” Rowland transmitted.

“Air Canada six twenty one, confirm the overshoot,” said the approach controller.

“Affirmative,” said Rowland.

“Okay sir, your intentions please?” the controller asked.

“Roger, we would like to circle back for another attempt on thirty two,” Rowland said.

“Sir, the runway is closed,” the controller said. “Debris on the runway. Your vector will be for a back course two three left. It is probably about the best. The surface wind is northwest at ten to fifteen. Turn right heading zero seven zero, three thousand feet.”

“Right zero seven zero, roger, three thousand,” Rowland read back.

As flight 621 approached 3,000 feet, heading in a wide arc to the east to circle the airport for an approach to runway 23L, the pilots were unaware of two crucial problems: first, that the number four engine had entirely departed the aircraft; and second, that their right wing was on fire. The lower wing surface, to which the engine pylon was attached, also formed the bottom of the fuel tank, causing a substantial breach when the engine ripped away; the fuel, thus liberated, ignited almost immediately, perhaps due to sparking between damaged electrical wires. With fuel continuing to pour from the ruptured tank and the broken engine feed lines, the fire soon became self-sustaining, eating through the wing structure in full view of the terrified passengers, even as the pilots themselves remained unaware. Air traffic controllers could also see the fire glimmering in the distance, but for whatever reason, no warning was ever issued to the crew.

Meanwhile, Captain Hamilton finally managed to observe the source of the power loss on his instruments, prompting him to call out, “We’ve lost [the] number four engine.”

“Have we?” Rowland said.

“Fuel. Fuel!” said Hill, noticing that the fuel flow meter for engine four was reading zero. The pilots’ initial conclusion was likely that the fuel feed lines to the engine had been damaged, starving it of fuel. In reality, there simply was no longer any engine to feed fuel to in the first place.

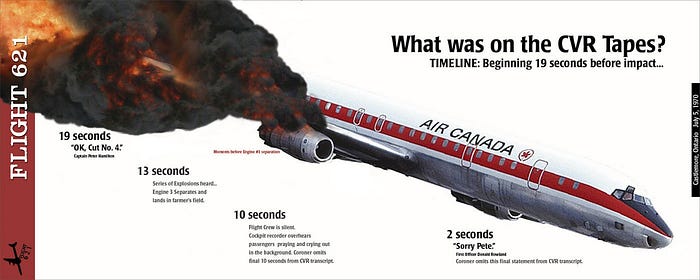

“Okay, cut number four,” Hamilton ordered.

“Number four engine?” someone asked.

“Yeah.”

“Number three engine — ” someone started to say. Indeed, the number three engine on the same side was running rough as well.

“Number four,” Hamilton affirmed.

“Number four, right?”

“Number three is jammed too,” Hamilton suddenly observed, noting difficulty with its fuel controls.

“Is it?” Rowland asked.

“There it is,” said Hamilton. “The whole thing is jammed.” Clearly the situation was more serious than they first thought.

Suddenly, a crackling noise was heard, like a small explosion.

“What was that?” Rowland asked. “What happened there, Pete?”

“That’s number — that number four — somethings happened!” Hamilton exclaimed.

“Oh look, we’ve got a-a — ” Rowland started to say. One might imagine that the final word would have been “fire,” but before he could utter it, a massive explosion rocked the plane, ripping off several large pieces of the outer wing skin as the fuel-air mixture in one of the tanks ignited.

“Pete! Sorry!” Rowland shouted.

Six seconds after the first blast, another even bigger explosion ripped through the plane, tearing away the number three engine and its pylon, which fell burning toward the countryside below.

“Alright — ” Hamilton said, trying to take stock of the situation.

Observing the engine falling to earth, the controller asked, “Six two one, the status of your aircraft please?”

There would be no reply. At that moment, the right wing, fatally weakened by the fire and explosions, gave way with a horrendous cacophony of tearing metal. A massive portion of the wing folded up and was torn asunder, sending the plane into an irreversible spiral, rolling toward the ground some 3,000 feet below.

“We’ve got an explosion!” Hamilton shouted.

“Oh look! We got flame–oh gosh!” Rowland exclaimed.

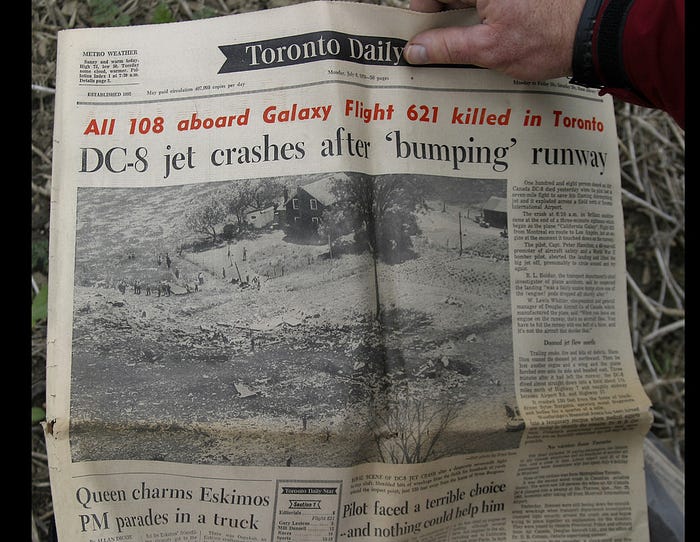

“We’ve lost a wing!” someone screamed. In a few terrible seconds, the plane plunged to earth, rolling inverted as it fell, corkscrewing down amid billowing smoke and fire. Moments later, banked about 90 degrees to the right with its nose pointed almost straight at the ground, Air Canada flight 621 slammed into a farmer’s field with a thunderous boom.

◊◊◊

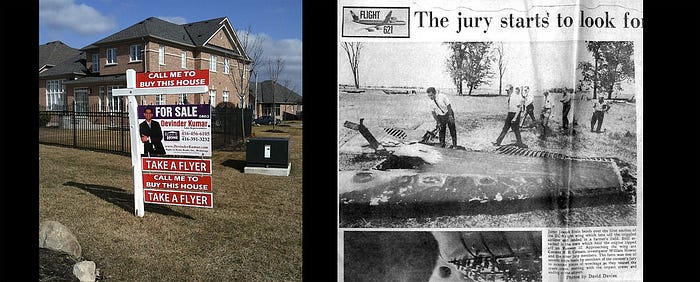

The immense force of the impact shattered windows in a nearby farmhouse, excavated a massive crater in the earth, and all but obliterated the DC-8 and its 109 unfortunate occupants. Although the owner of the farmhouse rushed outside to look for survivors, he couldn’t even find any complete human bodies — only small, mostly unidentifiable fragments. So forceful was the crash that it apparently left little possibility even for fire, and a motionless silence settled over the grisly scene, save for a dreadful hissing sound emanating from the ghastly crater.

As an army of first responders set about the difficult task of recovering and identifying the remains of the victims, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau expressed sorrow on behalf of all Canadians, and his Minister of Transport immediately appointed the Honorable Justice Hugh F. Gibson to lead a Board of Inquiry tasked with finding the causes and circumstances of the accident.

By examining the wreckage and reviewing the contents of the black boxes, air crash investigators working for the Board of Inquiry were able to lay down the basic sequence of events which led to the crash. The proximate cause was quite simple indeed: at a height of 60 feet above the ground, when Captain Hamilton called for the spoilers to be armed, First Officer Rowland inadvertently deployed the spoilers outright, severely reducing lift and causing the plane to drop hard onto the runway. The damage resulting from this impact included a fire which brought down the plane before the pilots could make another attempt to land. But to better understand what happened and why, the Board of Inquiry needed to answer three complex questions: first, could the plane have been saved at any point after the touchdown? Second, why did First Officer Rowland mistakenly deploy the spoilers? And finally, and perhaps most importantly, why was it possible to deploy the ground spoilers in flight at all?

◊◊◊

In an effort to understand whether the crash could have been averted at any point after the touchdown, investigators first needed to assess the extent and nature of the damage incurred during the hard landing. From the debris on the runway, it was evident that the number four engine and pylon had separated as a unit, taking with them an area of the lower wing skin about 1.2 meters long, 1.2 meters wide at the rear, and 0.6 meters wide at the front. The separation of the engine in this manner was expected in the event that the engine’s attachment points were subjected to a load greater than 7.0 G. The force of the impact against the runway was estimated at “only” 5.0 G, but due to the flexing of the wings, this force would have been amplified near the wingtips, resulting in a local vertical acceleration of at least 7.0 G near the outboard-mounted number four engine, explaining its separation. However, the engine’s attachment points had been designed in such a way that, should its ultimate limit load be exceeded, the engine and pylon would separate in a predictable manner without damaging the lower wing skin. The purpose of this measure was to prevent damage to the fuel tanks during a heavy crash landing. Unfortunately, however, the engine was likely subjected to a twisting motion which caused its attachments to fail out of sequence, allowing loads to be transmitted to the lower wing skin despite the manufacturer’s efforts to avoid this. The resulting damage caused fuel to escape from the number four alternate fuel tank, which ignited, probably due to flailing electrical wires.

There was no warning that would have informed the pilots of a fire on the exterior of a wing, and on some planes there still isn’t today. In general, such a fire should be readily visible, if not to the pilots themselves then at least to the cabin crew, passengers, or air traffic control. In this case, nobody informed the pilots of the fire until they realized its presence on their own, shortly before the crash. However, investigators determined that this likely made no difference, because the fire destroyed the right wing only two and a half minutes after the hard landing. Under the circumstances, that was probably not enough time for the pilots to have reached any runway. Readers may recall my article on BOAC flight 712, which suffered a similar fire on its wing after takeoff, but which nevertheless managed to get on the ground in one piece after 212 seconds in the air, which was considered an impressively quick turnaround. In contrast, the time from touchdown to wing failure on Air Canada flight 621 was only about 166 seconds, rendering a successful landing all but unimaginable.

Of course, the reason the plane took off again at all was because Captain Hamilton attempted to prevent the crash as soon as he recognized that the spoilers had been deployed. In accordance with his training, he pushed the engines to full power and pitched the nose up in an attempt to avoid hitting the ground, but given the plane’s rate of descent he could not possibly have succeeded. Had he not attempted to recover, the plane would have crashed on the runway, almost certainly resulting in the breakup of the airframe. This outcome probably would have been preferable for the majority of the occupants, who would have had some chance of survival, but simply letting the plane crash in this manner would have made no sense in the moment. The fatal consequences of the hard touch-and-go landing could scarcely have been predicted, while the dangers of a heavy crash landing were easily apparent. Certainly there was no reason to doubt Captain Hamilton’s decision to attempt a go-around, and we might even speculate that in ten alternate timelines, nine would have ended with the crew successfully landing their damaged airplane a few minutes later.

◊◊◊

Given the above, the point at which the sequence of events became essentially irreversible was found to be the moment when First Officer Rowland accidentally deployed the spoilers. After this, the crash could not reasonably have been prevented. But why did he do this in the first place? The plan was obviously to arm the spoilers so that they could deploy automatically on touchdown, not to deploy them in flight, and Rowland was clearly apologetic once he realized what he had done. Instead, the reasons for his mistake were unconscious, and rooted in events stretching back months.

According to witnesses and the pilots’ own remarks on the cockpit voice recording, it was apparent that Rowland and Hamilton had previously agreed to use one of two alternate spoiler procedures depending on who was flying. When Hamilton was flying, Rowland would deploy the spoilers manually on the ground, and when Rowland was flying, Hamilton would arm the spoilers during the flare just before touchdown. But on the accident flight, Hamilton decided to change it up, allowing Rowland to use his preferred method — arming the spoilers on the flare — even though he was not flying.

The problem here was that arming or deploying the spoilers is always accomplished by the non-flying pilot, so while Rowland preferred the spoilers to be armed on the flare, he never actually carried out this procedure himself. When flying with Hamilton, his muscle memory was to do things Hamilton’s way, by deploying the spoilers directly once the plane had touched down. As a result, he instinctively pulled the spoiler lever back to the “EXTEND” position instead of pulling it up to the “ARM” position, thus causing the spoilers to deploy before the plane touched the ground.

This mistake and its tragic consequences illustrated the reasoning behind Air Canada’s official procedure, which was to arm the spoilers during the Before Landing checklist while the plane was at least 1,000 feet above the ground. If this procedure had been strictly followed at all times, the act of pulling the spoiler lever back to deploy manually would never have entered Rowland’s muscle memory. And even if a pilot were to accidentally deploy the ground spoilers at that point, 1,000 feet was plenty of altitude to recover without endangering the flight. In fact, investigators noted, had Rowland deployed the spoilers as little as half a second earlier, Captain Hamilton would have had time to pull up enough to avoid damage (and conversely, had Rowland deployed the spoilers half a second later, the plane would have touched down so hard as to render it unable to become airborne again, ironically also a preferable outcome). The simple truth was that waiting to arm or deploy the spoilers until the plane was close to the ground greatly increased the risk of a serious accident, and for that reason investigators spent some time digging into the reasons why pilots were using these unapproved techniques in the first place.

As it turned out, the techniques had once been widespread at Air Canada due to a pervasive belief that the official procedure was unsafe. In the Captain’s instance, and probably in many others, these fears stemmed from an incident in the 1960s involving a Scandinavian Airlines DC-8, in which the spoilers, having been armed, deployed in flight due to an electrical fault. McDonnell Douglas later changed the design of the system to prevent this. Additionally, Captain Hamilton had expressed a belief that the 1966 crash of a Canadian Pacific DC-8 in Tokyo was also caused by an uncommanded spoiler deployment, although the official investigation (whose report he may not have seen) found that this was not the reason for the accident. Nevertheless, Hamilton had developed the perception that leaving the spoilers armed for any length of time was dangerous, and many other Air Canada pilots shared this belief. Furthermore, deploying the spoilers manually after touchdown apparently reduced the number of rough landings, making it an even more attractive option.

This practice was officially discouraged, but many pilots used it anyway, and management was generally kept in the dark. Check airmen, who oversee routine skill checks for pilots, were usually reluctant to penalize otherwise competent pilots for changing the spoiler procedure, sometimes because the check airmen themselves also favored the alternate technique. The result was that few reports about the behavior were made, and the practice was allowed to continue. Eventually, however, most of these pilots became uncomfortable with asking other crewmembers to deliberately deviate from official procedures, and in their efforts to find a balance between Air Canada’s policy and their own safety concerns, the practice of arming the spoilers “on the flare” was invented. This practice complied with Air Canada’s insistence that the spoilers be armed so as to deploy automatically, while still avoiding any extended flight with armed spoilers. Captain Hamilton apparently adopted this compromise procedure for the first time on the accident flight, as evidenced by his words, “Give them to me on the flare. I’ve given up. I’m tired of fighting it.”

However, on the DC-8–50 and -60 series aircraft flown by Air Canada, these safety fears were misplaced. The supposed danger of leaving the spoilers armed stemmed from the perceived unreliability of the plane’s weight-on-wheels sensors, which detect whether the nose gear strut is in compression, and thus whether the plane is on the ground. In early versions of the DC-8, this sensor was the sole source of air/ground data for the spoiler system, allowing a single erroneous signal to cause the spoilers, if armed, to deploy automatically in the air. However, later versions of the DC-8 incorporated a redundant system in which positive signals were required both from the weight-on-wheels sensor and from separate wheel speed transducers in the main landing gear. This meant that the probability of an erroneous “aircraft on ground” signal to the spoiler system was greatly reduced. But most Air Canada pilots were unaware of this fact, and so the misconceptions about the danger of armed spoilers persisted right up until the crash.

Evidently, the greater risk actually lay with the possibility that a pilot might inadvertently deploy the spoilers while close to the ground, which the alternate procedures — especially the “on the flare” procedure — rendered much more likely. Nevertheless, that left one glaring question: since the ground spoilers were (as the name suggests) only to be used on the ground, why was it even possible to deploy them in flight?

Interestingly, investigators discovered that the official McDonnell Douglas DC-8 aircraft manual would have one believe it was not, in fact, possible. The manual warned that the spoilers could be deployed in flight if the nose gear strut remained compressed after takeoff, but it also contained a blatantly false assurance that “a mechanical system operated by extension of the nose gear oleo strut” would prevent the spoiler lever from entering the extended position in flight under normal conditions. This simply was not true and never had been true on any DC-8. An electrical lockout system did prevent the spoiler lever from moving to the “EXTEND” position while the landing gear was stowed, but if the gear was down, there was absolutely nothing to stop a pilot from deploying the spoilers using the spoiler lever.

Some airlines had apparently discovered this discrepancy on their own, and a review of various DC-8 flight manuals found that Canadian Pacific, KLM, and Eastern Airlines all warned their crews that the spoilers could be deployed in flight if the landing gear was down. Air Canada, however, simply copied what was in the official McDonnell Douglas manual, writing that a “mechanical system” prevented the ground spoilers from ever being extended in flight. Furthermore, Air Canada’s training staff were unaware that this was possible, while the majority of Air Canada’s DC-8 pilot cohort was reportedly “unsure” when asked. Some pilots had discovered this possibility on their own, however, and one even reported it to management. In a letter following his discovery, this pilot suggested that the procedure be changed to call for arming the spoilers “on the flare,” but the Director of Flight Operations rejected the proposal, writing that it would increase the risk of a pilot inadvertently deploying the ground spoilers at a low altitude where recovery would be impossible — essentially predicting the crash of flight 621. He did not appear to realize that many pilots were already using the technique, with disastrous results.

◊◊◊

When asked to explain the discrepancy between the plane and its documentation, McDonnell Douglas was able to shed some light on the design history of the spoiler system. On the original DC-8–40 series, the design assumption was that the pilots would have no need to deploy the spoilers manually, because the DC-8 did not use spoilers as speed brakes in flight. For the other use cases, as roll assist and as braking devices, automatic deployment was preferable. However, as mentioned earlier, the air/ground sensors on these early DC-8s were not very reliable, and if the sensor failed to send a signal that the plane was on the ground, the spoilers might not deploy automatically on touchdown even if they were armed. Without the spoilers, braking power is severely reduced, and spoiler system failures have contributed to a number of runway overrun accidents over the years. McDonnell Douglas therefore recognized a need for a manual backup that would allow the pilots to deploy the spoilers by force if a malfunction of the air/ground system prevented them from deploying automatically. For this purpose, the manufacturer installed a spoiler lever allowing manual deployment regardless of the plane’s air/ground status, as long as the landing gear was down. This solution mitigated the risk of the spoilers failing to deploy on the ground, but it did not appear that McDonnell Douglas adequately considered the risk of a pilot inadvertently using the manual override in the air. In their view, no pilot should touch the lever after the Before Landing checklist at 1,000 feet above the ground, where an inadvertent spoiler deployment would have minimal consequence. The risk of a pilot deploying the spoilers while close to the ground was dismissed — after all, the engineers thought, why would a pilot ever do that?

◊◊◊

Unfortunately, it’s not possible with current technology to completely exclude all pilot inputs that could lead to a crash. AI could change that in the semi-distant future, but right now this statement remains true, and it was certainly true in the late 1950s when the DC-8 was designed. As my article last week illustrated, a pilot can, given sufficient willpower and disregard for life, cause a plane to crash simply by using the controls to fly it into the ground. Nevertheless, we can’t simply take away a pilot’s ability to pitch down, which is why engineers continually assess the relative merit vs. risk of allowing systems to accept situationally dangerous pilot inputs. Many systems on large airliners do have built-in safeguards — for example, pilots cannot normally retract the landing gear while the plane is on the ground, nor can they intentionally deploy the thrust reversers in flight (except on planes where this is envisioned, of which the DC-8 is the most notable example). In the case of the DC-8’s ground spoilers, the trade-off made sense on the original DC-8–40, but investigators noted that on the later DC-8–50 and -60 series, which had solved the reliability problems with the air/ground system, the need for a manual spoiler deployment mechanism was not as apparent. Despite this, the relative merits and risks of retaining the manual override option were apparently not reconsidered.

As for why the official aircraft manual claimed the spoilers could not be deployed in flight, the Board of Inquiry’s report does not suggest that McDonnell Douglas ever furnished an answer.

◊◊◊

As a result of its findings, Justice Gibson and the Board of Inquiry issued eight recommendations, including that McDonnell Douglas change the design of the ground spoiler system and correct its manuals; that Air Canada make sure its pilots are adhering strictly to standard procedures; and that Transport Canada review manufacturers’ aircraft manuals and airlines’ operating manuals in order to ensure consistency between and among them. Given today’s higher standards of documentation, it’s hard to imagine that a manual could proclaim the existence of a safety system that doesn’t actually exist. Nevertheless, the exact responses of various parties to the recommendations are difficult to verify, because the current Transportation Safety Board of Canada does not retain correspondence related to recommendations from before the agency was created in 1990. So was the design of the DC-8 changed? It’s possible that it was, but research for this article did not confirm it. As for the type more broadly, no similar accidents ever again occurred, and the last DC-8s equipped to carry passengers were retired in 2013, except for one still operated by the Evangelical organization Samaritan’s Purse.

Meanwhile, the crash site itself was initially turned back into farmland, and remained as such for over 30 years, until members of the public began discovering debris and fragmented human remains in the field where the plane came down. The discoveries drew attention back to the crash, and when the site later came into the possession of developers, plans were laid to preserve the location as a memorial. The place where flight 621 came down now sits next to a subdivision in the growing Toronto suburb of Brampton, although a gap in the last row of houses kindly permits the existence of an expansive and well-kept memorial garden, established in 2013.

With more than 50 years having passed since the disaster, the specific causes appear ever more as products of their time, but some of the general lessons still hold true. The engineering checks and balances which decide the limits of pilot authority are still occasionally miscalculated, as I discussed in my 2022 article on the Scaled Composites SpaceShipTwo. And the very human mistake of pulling the wrong lever, or pulling the right lever in the wrong direction, or at the wrong time, remains ever-present. In January 2023, for instance, Yeti Airlines flight 691 crashed in Nepal, killing 72 people, after the non-flying pilot apparently grabbed the wrong lever and feathered both propellers instead of extending the flaps. It seems almost prosaic to suggest, but the best way to prevent these sorts of “wrong lever” accidents both now and in 1970 was and is to adhere strictly to standard procedures, call out configuration changes, and maintain good situational awareness. The design of the DC-8 played a major role in the crash of Air Canada flight 621, but at the end of the day, 109 lives could still have been saved if the pilots had simply flown by the book.

_______________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit

Support me on Patreon (Note: I do not earn money from views on Medium!)

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 240 similar articles