Words of Warning: The crash of Delta flight 1141

On the 31st of August 1988, the pilots of a Delta Air Lines Boeing 727 joined the taxi queue at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, chatting it up with a flight attendant as they waited for their turn to take off. They talked about recent airline accidents, discussed the habits of birds, shared their thoughts on the 1988 presidential election, and joked that they should leave something funny on the cockpit voice recording in case they crashed. Little did they know their words would be prophetic. Just minutes later, Delta flight 1141 failed to become airborne and overran the runway on takeoff. The Boeing 727 slammed back down in a field and burst into flames, killing 14 of the 108 people on board. It didn’t take long for investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board to discover why: the pilots, distracted by their off-topic conversation, had failed to configure the plane properly for takeoff. But that turned out to be only part of the story. Investigators also discovered bad maintenance practices that led to the failure of a crucial warning, a dangerous psychological quirk that prevented the pilots from noticing their mistake, and a disturbing history of near misses at Delta that suggested an accident was inevitable.

Delta Air Lines flight 1141 was a regularly scheduled service from Jackson, Mississippi, to Salt Lake City, Utah, with a stopover in Dallas, Texas. In command of the Boeing 727 operating this flight on the 31st of August 1988 were three experienced pilots: Captain Larry Davis, First Officer Wilson Kirkland, and Flight Engineer Steven Judd. After the short flight from Jackson, the crew arrived in Dallas at 7:38 a.m., whereupon 101 passengers boarded for the next leg to Salt Lake City. Also joining them were four flight attendants, making for a total of 108 people on board.

It is common for pilots to get to know each other well over the course of a day’s work, and this crew was certainly no exception. Davis, Kirkland, and Judd conversed amicably about a wide range of topics while waiting at the gate, which was a routine and even beneficial habit shared by all airline pilots. However, the conversation must end as soon as the engines are started. This is called the sterile cockpit rule. After several accidents in which crews were distracted by off-topic discussions, regulatory authorities banned non-pertinent conversation after engine start and below an altitude of 10,000 feet. After reaching this altitude, the pilots would once again be free to talk about whatever they wanted.

However, it didn’t always work that way. In 1988, the sterile cockpit rule was still relatively new, and many captains had been flying since before it was introduced. Nor was it easy to enforce, and violations were thought to be relatively frequent. Enforcement relied on the captain laying down the law and preventing other crewmembers from engaging in off-topic conversation, but as it turned out, Larry Davis wasn’t that sort of captain. First Officer Kirkland continued to make various idle comments throughout the engine start checklist and pushback from the gate, and Captain Davis made no attempt to stop him.

Three minutes after pushback, flight 1141 still hadn’t received permission to start taxiing.

“How about looking down our way while we still have teeth in our mouths?” said Flight Engineer Judd. His comment was met with hearty laughter.

“Growing gray at the south ramp is Delta…” said Kirkland.

At this point, Captain Davis decided to shut down one of the 727’s three engines to save fuel while idling on the parking apron. “I guess we ought to shut down number three and save a few thousand dollars,” he said. Kirkland told Judd to inform the ground controller and to request two minutes warning before being given takeoff clearance so that they would have time to restart the engine.

Delta flight 1141 was soon given clearance to begin taxiing, and the 727 joined a long queue of airliners crawling its way across the vast expanse of Dallas Fort Worth International Airport (or DFW). The controller ordered them to give way to another plane joining the queue ahead of them, to which Davis indignantly commented, “We certainly taxied out before he did!”

Meanwhile, Judd began to read off the taxi checklist, the list of tasks that need to be completed in order to configure the plane for takeoff. As Judd read off each item, Kirkland took the appropriate action and called out his standard response.

“Pitot heat?”

“It’s on.”

“Airspeed and EPR bugs?”

“Thirty-one and forty-five on both sides and alternate EPR set.”

“Altimeter and flight instruments?”

“Set, cross checked.”

“Stab trim?”

“Uh, five point six.”

At this point, a flight attendant entered the cockpit. (Although media at the time incorrectly reported that this flight attendant was Dixie Dunn, sources close to the crew have confirmed that it was actually Mary O’Neill.) She quickly proved far more interesting than the still incomplete taxi checklist. “A lotta people goin’ out this morning,” she said in her perfect southern drawl.

“Yeah, big push,” said Judd.

For the next seven and a half minutes, First Officer Kirkland chatted with O’Neill, while Davis and Judd occasionally pitched in to offer their own two cents on a wide range of issues. Much of the discussion centered on recent plane crashes, including the 1985 crash of Delta flight 191 at DFW. The discussion also touched on the 1988 presidential race, about which Kirkland had much to say. He criticized the media’s treatment of Dan Quayle, discussed the appearance and oratory skills of Quayle’s wife, and commented that it was “scary” that Jesse Jackson got as far as he did. For her part, O’Neill played along, agreeing that reporters were, by and large, “vultures.”

Twelve minutes after pushback, and still nowhere near the runway, flight 1141 seemed to be stuck in taxi limbo. The ground controller finally gave them their next set of instructions, after which the pilots and O’Neill immediately jumped back into their conversation, which had by now expanded to include Kirkland’s military experience, drink mixes, and several other topics unrelated to flight operations.

The conversation eventually turned to the 1987 crash of Continental flight 1713 in Denver; in particular, Kirkland was concerned with how the media had gotten ahold of part of the cockpit voice recording in which the pilots had been heard discussing the dating habits of their flight attendants. “You know, we forgot to discuss about the dating habits of our flight attendants so we could get it on the recorder, you know — in case we crash, the media will have some little juicy tidbit…” he said.

“Ooooh, is that right?” said O’Neill. “Is that what they’re looking for?”

“Yeah, you know that Continental that crashed in Denver?” said Kirkland. “You know, they were talking about the dating habits of one of their flight attendants — we gotta leave something for our wives and children to listen to!”

Some minutes later, O’Neill commented, “Are we gonna get takeoff clearance or are we just gonna roll around the airport?”

“Well, we thought we were gonna have to retire sitting there waiting for taxi clearance,” Kirkland joked.

Immediately afterward, the conversation went off the rails once again. Beginning around 8:53, Kirkland pointed out a flock of egrets gathering in the grass near the taxiway and asked, “What kind of birds are those?”

“Egrets, or whatever they call ‘em,” said Davis.

“Yeah, Egrets,” said O’Neill.

“Are they?”

“I think so,” said O’Neill. “Are they a cousin to the ones by the sea?”

The pilots now discussed their experiences with egrets for some time before discussing recent improvements in DFW’s handling of traffic congestion. Then at 8:56, a bird got hit by a jet blast and was thrown a considerable distance, which proved to be another amusing distraction. Once again the conversation turned to the habits of various species of birds, including how the gooney birds on Midway Island would come back to nest in the exact spot where they were born, even if that turned out to be the middle of the runway. Finally, at 8:57, Judd went on the public address system to order the flight attendants back to their stations, finally putting an end to the conversation.

Seeing that they were now fourth in line for takeoff, the pilots initiated the sequence to restart the number three engine. But at the moment it came online, the controller unexpectedly cleared them to taxi to the runway and hold for takeoff, bypassing the three planes ahead of them in line. This left very little time at all to finish the taxi checklist and the before takeoff checklist that was supposed to follow it.

As the plane approached the head of the runway, Judd read off each item on the taxi checklist and Kirkland fired back immediately with the appropriate response. There was just one problem: he was going by rote memorization and wasn’t actually checking each of the settings that he was reading back.

“Engine anti-ice?”

“It’s closed.”

“Shoulder harness?”

“They’re on.”

“Flaps?”

“Fifteen, fifteen, green light.”

The flaps were supposed to be extended to 15 degrees on takeoff to increase the lift provided by the wings, allowing the plane to become airborne at a lower speed. Had Kirkland actually checked the position of the flaps when Judd asked about them, he would have realized that no one had yet extended them to 15 degrees, and that the associated indicator light was not in fact green. But he didn’t check; instead he just gave the correct response out of habit, completely negating the purpose of the checklist.

With the flaps retracted, it is still possible to become airborne, but liftoff will occur at a much higher speed and the rate of climb will be significantly reduced. However, pilots plan in advance to lift off at a particular speed that is calculated based on the plane’s expected performance with the flaps extended, and if they attempt to lift off at that same speed with the flaps retracted, the plane will not fly. For that reason, all planes are fitted with a takeoff configuration warning system that sounds an alarm if the throttles are advanced to takeoff thrust with the flaps in the wrong position. This should have served as a last line of defense for the crew of Delta flight 1141, but there was a problem: the system wasn’t working.

When the throttles are advanced, an actuator arm moves forward and a button on the arm makes contact with a plunger, which is pushed back into a recess to complete the alarm circuit. If the plunger is depressed and the flaps are in the retracted position, the circuit will energize and the alarm will sound. However, on this 727, the end of the actuator arm had not been adjusted properly, and it sometimes slid past the plunger instead of depressing it. Corrosion around the plunger also inhibited its ability to sustain an electrical current. As a result, the takeoff warning system was extremely unreliable. It had been flagged as “weak and intermittent” three weeks before the flight, so mechanics replaced the warning horn, but did not check the actuation system. It just so happened that the warning worked during their post-maintenance test, and the plane was put back into service, even though the root cause of the failure had not been addressed.

Just as Kirkland and Judd finished the before takeoff checklist, flight 1141 taxied onto the runway and began its takeoff roll. Captain Davis accelerated the engines to takeoff power, and the faulty warning didn’t go off, preventing the crew from realizing their mistake. The plane accelerated through 80 knots, then VR — rotation speed. Davis pulled back on the control column and the nose came up, but the plane struggled to get off the ground. The wings weren’t providing enough lift due to the retracted flaps. He pulled up more, causing the tail to strike the runway. Finally, the 727 lurched into the air, but only barely. Without enough lift to climb, it immediately approached a stall, and the stall warning activated, shaking the pilots’ control columns. The correct response to a stick shaker warning on takeoff is to apply max power and reduce the pitch angle, but the pilots didn’t do this.

“Something’s wrong!” Davis shouted.

As the plane skimmed along in a nose-high attitude just barely above the ground, turbulent air rolling over the plane’s partially stalled wings disrupted airflow into the rear-mounted engines. In the absence of proper airflow from front to back through the engine, compressed air from inside the compression chamber burst back out through the engine inlet, an event known as a compressor stall. The engines emitted a series of fiery bangs that rocked the entire plane, and thrust began to drop.

“Engine failure!” someone yelled. But the engines had not in fact failed. If the pilots reduced their pitch angle to smooth out airflow over the wings, they would have started working properly again.

“We got an engine failure!” said Kirkland.

Hovering on the edge of a stall, the plane swayed wildly from side to side, causing the right wingtip to strike the runway. Captain Davis furiously manhandled the yoke in an effort to maintain control. The plane rose to a height of 20 feet above the ground, then descended again. As they hurtled toward the end of the runway, Davis yelled, “We’re not gonna make it!”

Kirkland keyed his mic and attempted to broadcast a distress call to air traffic control. “Eleven forty-one’s — ” he started to say.

“Full power!” said Davis. But it was too late. Less than one second later, the 727’s right wing clipped the instrument landing system antenna, sending the plane crashing back to earth. Flight 1141 slid for several hundred meters across the grass overrun area, its right wing disintegrating as it bounced over a ditch and up an embankment. Skidding sideways, the plane rolled left, broke into three pieces, and ground to a halt just short of the airport’s perimeter fence. Flames immediately erupted from the ruptured fuel tanks, sending a column of black smoke rising over Dallas Fort Worth International Airport.

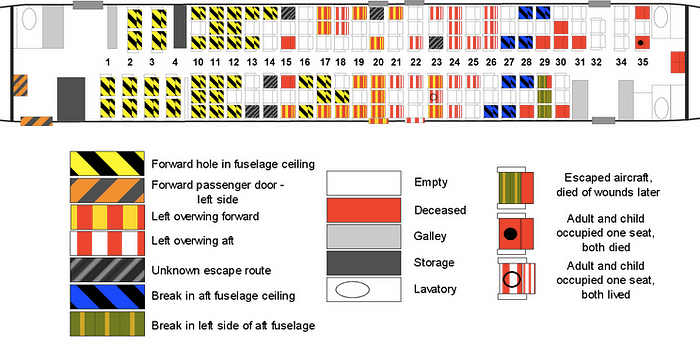

Immediately after the plane came to a stop, all 108 passengers and crew were miraculously still alive. Many people had suffered minor injuries, but none were debilitating. However, within moments it was clear that the danger was far from over. A rapidly growing blaze began in the tail section and spread under the plane, emerging near the left wing. Flight attendants hurried to open the exit doors as frantic passengers fled before an advancing wall of noxious smoke. One of the rear flight attendants attempted to open the left rear galley door, but found that it had become jammed in its frame during the crash and wouldn’t open. Passengers at the front and center sections managed to escape through the main doors and through breaks in the fuselage, emerging into the daylight as smoke continued to pour from the plane. Others were not so lucky: two flight attendants and eleven passengers who had lined up for the broken rear galley exit were overcome by thick, black smoke and perished from carbon monoxide poisoning. By the time firefighters arrived on the scene four minutes after the crash, it was already too late to save them.

As dozens of passengers were rushed to hospital, firefighters entered the plane and extracted the three badly injured pilots from the cockpit, making them the last to leave the plane alive. Rescue crews also discovered the bodies of thirteen people in the back of the plane, including that of flight attendant Dixie Dunn. Another passenger who had re-entered the plane to try to save his family suffered severe burns and died in hospital 11 days after the crash, bringing the final death toll to 14 with 94 survivors. However, it could have been worse: it would later be noted that the recently-mandated fire retardant properties of the passenger seats slowed the spread of the blaze into the cabin, increasing survival time by 90 seconds and doubtlessly saving lives.

Investigators from the National Transportation Board soon arrived on the scene to determine the cause of the accident. Although the flight data recorder didn’t directly record the position of the flaps, physical evidence and a study of aircraft performance showed conclusively that the crew had not extended the flaps for takeoff. An inspection of the takeoff configuration warning system also revealed inadequate maintenance that prevented the alarm from sounding, sealing their fate. In November 1988, the Federal Aviation Administration issued an airworthiness directive requiring inspections of Boeing 727 takeoff warning systems, resulting in the discovery of similar problems on several additional airplanes, all of which were repaired.

The cockpit voice recording revealed that the failure to extend the flaps was directly related to the pilots’ off-topic conversation with the flight attendant, which interrupted the taxi checklist and used up time that could otherwise have been spent completing it. It was a classic example of why the sterile cockpit rule existed in the first place. Investigators placed a significant portion of the blame on First Officer Kirkland, who was the driving force behind all the off-topic discussions, but also faulted Captain Davis for fostering a cockpit environment in which such violations were perceived as permissible. Had he simply said, “Hey, let’s keep it on topic,” the crash almost certainly would not have happened.

However, this lack of discipline was apparent not just in the violation of the sterile cockpit rule. In its report, the NTSB wrote, “The CVR transcript indicated that the captain did not initiate even one checklist; the [flight engineer] called only one checklist complete; required callouts were not made by the captain and [flight engineer] during the engine start procedure; the captain did not give a takeoff briefing; and the first officer did not call out ‘V1.’” Clearly the problems went deeper.

As it turned out, Davis had received almost no guidance on what sort of cockpit atmosphere he was expected to foster. Delta had a long-standing practice of giving captains wide discretion over procedural matters rather than strictly enforcing a set of cockpit norms handed down from on high. This resulted in a wide degree of variability from one captain to the next. Delta pilots interviewed after the crash couldn’t agree on who was responsible for checking the position of the flaps or who was supposed to ensure that checklists had been completed. This sort of confusion might have caused the pilots to miss a specific opportunity to prevent the crash. The air conditioning auto pack trip light was supposed to illuminate on takeoff, but would not do so if the plane was not configured correctly, or if the A/C pack trip system had otherwise failed. Flight Engineer Judd noticed the absence of the light at the beginning of the takeoff roll, but thought he didn’t have to inform the captain; however, Captain Davis was sure that the flight engineer would have told him. If Judd had mentioned the light, Davis and Kirkland could have realized something was wrong.

The NTSB already knew that Delta’s lack of cockpit discipline was causing problems. In fact, in 1987 Delta suffered no less than six serious incidents and near misses that were blamed on pilot error. First, a crew inadvertently shut down both engines on a Boeing 767 in flight, causing a total loss of power, before they managed to restart them. Then, a Delta Lockheed L-1011 deviated more than 95 kilometers off its assigned airway while crossing the Atlantic Ocean. The flight strayed into the path of a Continental Boeing 747, and the two planes with a combined 583 people on board came within thirty feet of colliding. Subsequent to this, a Delta flight landed on the wrong runway; another flight landed at the wrong airport; and two flights took off without permission from air traffic control. Any one of these incidents could have resulted in a major disaster. Something was seriously wrong at Delta Air Lines, and the string of near misses suggested that an accident caused by pilot error was probably inevitable. If it hadn’t happened to Davis, Kirkland, and Judd, it would have happened to some other flight crew sooner or later.

As a result of the 1987 incidents, the FAA had launched an audit of Delta’s flight operations, which discovered widespread communication breakdowns, a lack of crew coordination, and frequent lapses in discipline. The airline was also found to be violating regulations by not recording pilots’ unsatisfactory performances during proficiency checks, instead extending the test until the pilot under examination finally got it right. As a result of the 1987 audit, Delta vowed to update numerous checklists, start training its pilots to emphasize checklist details, update its training program to improve standardization, and hold pilots to higher standards during routine proficiency checks. But after the Delta 1141 accident, a follow-up audit found that while most of the simpler changes had been made, the bigger overhauls were still in the development phase. Most critical was Delta’s incipient cockpit resource management training program. Cockpit resource management, or CRM, is meant to facilitate clear and open communication between crewmembers, allowing them to effectively utilize their collective expertise to solve problems and catch deviations before they can escalate. Delta’s CRM training program was scheduled to begin in 1989 — too late for the pilots of flight 1141.

After the 1988 audit, Delta reorganized its entire training department, creating new leadership posts and new chains of command with new safety-related mandates. This represented a massive step in the right direction, as the NTSB has long maintained that safety in crew performance is initiated from the top down, and that the management must first realize their own role in promoting a safety culture before such a culture can arise. In its report on the crash, the NTSB quoted an article by G.M. Bruggink in Flight Safety Digest: “An attitude of disrespect for the disciplined application of checklist procedures does not develop overnight; it develops after prolonged exposure to an attitude of indifference.” Through its fundamental reorganization of its training and flight operations departments, Delta thoroughly routed this culture of indifference that had slowly built up over the preceding decades. Most likely as a result of these changes, as well its introduction of CRM, Delta has not had another fatal crash due to pilot error since flight 1141.

However, some of the fundamental pitfalls that led to the crash didn’t only apply to Delta. Investigators were fascinated by the fact that First Officer Kirkland had called out the correct flap setting out of habit without noticing that the flaps were not set correctly. Flight Engineer Judd later recalled another incident in which a first officer had called out “flaps 25” even though the flaps were mistakenly set to 15 degrees, simply because “flaps 25” was what he was expecting to say. And just one year earlier, a Northwest Airlines MD-82 had crashed on takeoff from Detroit, killing 156 people, because the pilots had failed to extend the flaps for takeoff. So this clearly was not an isolated problem — pilots across the country were vulnerable to the same mistake. As a result of the Delta crash at DFW, the FAA took action to implement changes to checklist design, first recommended after the Northwest Airlines crash, that the NTSB hoped would improve compliance with procedures. The NTSB also recommended that flight operations manuals clearly state which crewmember is responsible for ensuring checklists are complete, and reiterated a previous recommendation that CRM — which had previously been encouraged but not required — be mandated for all airline pilots.

There was one final change that came out of the crash of Delta flight 1141 — one that was foreshadowed on the cockpit voice recording. During the NTSB’s public hearings regarding the accident, the tape of the cockpit conversations was released to the media, where the pilots’ jokes about the dating habits of flight attendants and about the CVR itself immediately made national news. These sections of the conversation had even been redacted from the transcript in the accident report to preserve the pilots’ privacy, but the release of the full tape rendered this pointless. Parts of the tape are still out there and anyone can listen to them. In fact, this was exactly the sort of media opportunism that the pilots had railed against while taxiing away from the gate at DFW, and they were deeply hurt by the tape’s release. All three pilots had already been fired from Delta Air Lines, and although Judd was later rehired, Davis and Kirkland would never fly again. Becoming the punchline of a national joke was like rubbing salt in the wound. Unwilling to tolerate such public humiliation, the pilots of flight 1141 and other pilots around the country successfully lobbied to prevent the NTSB from releasing raw cockpit voice recordings. Since 1988, raw CVR audio clips have only been released when submitted as evidence in a court of law. In a roundabout way — which unfortunately involved the deaths of 14 people — Kirkland’s offhand complaints about the media’s treatment of pilots’ private conversations actually resulted in meaningful change.

_____________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit!

And don’t forget to visit r/admiralcloudberg, where you can read over 130 similar articles.