Wrong Turn at Taipei: The crash of Singapore Airlines flight 006

On the 31st of October 2000, a Singapore Airlines Boeing 747 lined up for takeoff at Chiang Kai-shek International Airport in Taipei, Taiwan. Outside the plane, the outer bands of the approaching Typhoon Xangsane strafed the runway, battering the windows with wind-driven rain, but on the flight deck, all seemed in order. That is, until a forest of objects appeared without warning out of the darkness — concrete barriers, excavators, steamrollers, piles of rebar, all directly in their path. The plane plowed into them like bowling pins, and in a matter of seconds, the 747 was sliding down the runway to its doom, engulfed in flames. By the time it was over, 83 of the 179 people on board were dead, ending 28 years of perfect safety at Singapore Airlines.

Within a relatively short time, the proximate cause of the crash became clear: inexplicably, the experienced 747 crew had attempted, unknowingly, to depart from a runway that was closed for construction. Even more baffling, the pilots were fully aware that the runway was closed, but believed, despite evidence to the contrary, that they were on the correct runway, which was open. How could this happen? Who was to blame — the pilots, or the airport? There are still no simple answers to these questions, but a deep dive into the long and murky error chain leading up to the disaster reveals important truths about human inadequacies, and how a poorly designed operating environment can, with a little bit of bad luck, lure even the best pilots into a truly elementary mistake.

◊◊◊

For over 50 years, Singapore Airlines has been the international face of its eponymous Southeast Asian city-state, bringing attention and wealth into the tiny but affluent country from all corners of the world. The airline has consistently ranked among the top 10 in the world in terms of revenue passenger kilometers,* and also frequently makes appearances in the top 5 safest airlines, according to industry groups, as well as the top 5 best airlines for passengers, according to travel publications.

For most of its existence, passengers boarding a Singapore Airlines flight have had little reason to fear catastrophe. The airline’s pilots are well trained, its planes are well maintained, and its fleet consists mainly of the latest models, whatever they happen to be. And yet, bookended between periods of 28 and 22 years without a fatal accident, lies a single black mark on the airline’s otherwise perfect record.

*1 RPK = 1 paying passenger carried 1 kilometer

The story began on Halloween night of 2000, when a Singapore Airlines Boeing 747–400, registration 9V-SPK, arrived at Chiang Kai-shek International Airport in Taipei, the capital city of Taiwan. The stop in Taipei was to be a brief respite before the transpacific flight 006 to Los Angeles, California, which was too far away for the 747 to reach directly from Singapore; at that time, non-stop services to the United States had not yet begun. The double decker 747 was one of two that Singapore Airlines had painted in a colorful tropical-themed livery, which would have been quite striking during the day, but probably went unnoticed by most of the passengers, who boarded the plane well after nightfall. In fact, most were probably much more concerned about the weather: at that time, typhoon Xangsane was centered 350 kilometers south of the airport and was steadily moving north at a speed of 12 knots, bringing with it sustained winds of 75 knots and gusts to 90, the equivalent of a Category I hurricane. By late evening on the 31st of October, Xangsane’s outer thunderstorm bands were already beginning to affect Chiang Kai-shek Airport, and heavy rain was falling with reported winds of 36 knots and gusts to 52.

In charge of shepherding 159 passengers and 17 flight attendants through the storm that night was a three-person cockpit crew, led by 41-year-old Captain Foong Chee Kong, a Malaysian national with over 11,000 flying hours and an above average training record. Joining him were two Singaporean first officers, 36-year-old Latiff Cyrano and 38-year-old Ng Kheng Leng, who had about 2,400 and 5,500 hours, respectively. For flight duty time reasons, Ng was rostered as relief pilot, taking over for First Officer Latiff part way through the flight, but until then he was to act as a cockpit observer with no specific duties.

Before the flight, the pilots had received and reviewed a large stack of paperwork containing everything they might need to know, from the latest weather reports to various Notices to Airmen (NOTAMs), and much besides. Although NOTAMs are notoriously bothersome to read, the pilots did manage to spot what is for the purposes of this story the most important piece of information, which was that one of Chiang Kai-shek Airport’s three runways was closed for construction.

When the airport was originally designed in the early 1970s, the plan was to have two runways, consisting of a longer runway designated 05/23 (depending on the direction of use) and a shorter runway designated 06/24. However, the closure of one of these runways, especially the longer 05/23, would have had a negative impact on the airport’s capacity, so at an advanced stage of construction it was decided that a third runway would be added, running between and parallel to the terminal and runway 05/23. To accomplish this, a taxiway beside runway 05/23 was reinforced and equipped with basic runway markings and lighting, becoming runway 05 Right / 23 Left, while the original runway became runway 05 Left / 23 Right.

Runway 05R/23L was never very useful as a runway. Its basic lighting meant that it could only be used for takeoffs, not landings, and only in good weather, but that was the least of its problems. Because it was originally a taxiway, the runway was exceptionally narrow, and it was also too close to the terminal, such that large aircraft parked at the A gates impinged upon its lateral obstacle clearance limits, which usually prevented pilots from using it even if they wanted to. Its proximity to the parallel taxiway NP also meant that planes could not use runway 05R if there was even a minimal crosswind, due to the risk of striking taxiing aircraft.

As a result of these factors, runway 05R/23L was effectively useless, and as the turn of the millennium approached, the airport authorities decided that it should be turned back into a taxiway. Therefore, on October 3rd, 2000, Taiwan’s Civil Aeronautics Administration announced that runway 05R/23L would be “re-designated” as taxiway NC, effective from 17:00 UTC on November 1st. On October 23rd, however, this re-designation was postponed indefinitely due to delays in the importation of taxiway signage.

In the meantime, the airport authorized repairs to the pavement in the middle section of runway 05R/23L, between the intersecting taxiways N4 and N5. It’s unclear whether these repairs were associated with the runway’s pending re-designation, but the official report implies that they may have been entirely unrelated. As a result, the center part of runway 05R/23L was cordoned off, while both ends of the runway remained open for taxiing aircraft. This was what the runway had mostly been used for all along, since it provided a convenient route to the head of runway 05L, as opposed to taxiway NP, which ran close to the A gates and was often congested. Therefore, the only change brought on by the construction was that planes would be temporarily unable to taxi along the entire length of the runway.

To reflect this change, the CAA issued a NOTAM informing pilots of the partial runway closure, and concrete jersey barriers painted in conspicuous colors were erected around the work area. Within this concrete cordon, several areas of runway surface had been torn out, and various construction vehicles were parked there, including excavators, steamrollers, and other equipment, along with piles of raw materials. Outside the lighted construction zone, however, there were no runway closure markings or any other indication that the runaway was unusable — or at least any more unusable than usual — for the simple reason that both ends were in fact still being used.

◊◊◊

Meanwhile, as the clock ticked past 23:00, the pilots of Singapore Airlines flight 006 prepared their aircraft for departure. As they finished the pre-flight checks and began starting up the engines, Captain Foong was careful to remind his crew to take things slowly and avoid rushing. With the typhoon bearing down, there was a risk of psychological pressure, but he knew they had plenty of time to leave before conditions became untenable, and until then haste was more dangerous than the storm.

Among other pre-flight activities, the pilots calculated the crosswind component on takeoff, finding it to be within limits. They also decided that they would take off on the longer runway 05L, rather than runway 06, which was more commonly used by Singapore Airlines. None of the pilots had taken off from 05L in at least three years, but the extra length would be beneficial if they had to abort the takeoff, seeing as the runways were wet.

As flight 006 prepared to push back from the B gates, the air traffic controller notified them of the expected taxi route, which would take them down taxiway SS, to the right onto the West Cross taxiway, left onto taxiway NP, then right onto taxiway N1 and right again onto runway 05L.

As demanded by both good judgment and company procedures, Captain Foong briefed the taxi route so that the rest of the crew would know exactly what to expect. “Yah, so you go straight down,” he began, presumably pointing at a map.

“Roger that,” said First Officer Latiff.

“Hit West Cross, go across the West Cross, then November Papa all the way down, okay,” Foong continued.

“Okay,” said Latiff. “Then come down further south, ah.”

“Okay, alright,” Foong concluded.

At about 23:07, flight 006 pushed back from the gate and began taxiing. Captain Foong announced that they would “taxi slowly” in order to avoid skidding on the soaking wet taxiways, a prudent move under the conditions. The pilots also discussed contingencies in case the weather prevented them from returning to runway 05L in an emergency, another sign that they were covering their bases.

After performing standard control checks, verifying the airplane’s configuration, and re-briefing their takeoff speeds, the pilots carefully taxied down to the West Cross taxiway, turned right, and proceeded toward taxiway NP. Captain Foong again commented, “I am going to go very slowly here, okay, because you’re going to get skid.”

“Okay, nine knots,” First Officer Latiff called out.

As they taxied, high winds rocked the plane, making some passengers nervous. “The weather radar will be all red, haha,” relief pilot Ng joked.

“Coming up, er, November Papa,” Latiff said.

“Okay, all the way down, left turn, all the way down,” Captain Foong said, steering the plane onto taxiway NP. Both pilots verbally confirmed the location and direction of the turn, ensuring that it was accomplished correctly.

Proceeding down taxiway NP, they called air traffic control for further instructions. “Taipei tower, good evening, Singapore six,” said First Officer Latiff.

“Singapore six, good evening, Taipei Tower, hold short runway zero five left,” said the controller.

“Hold short runway zero five left, Singapore six,” Latiff read back.

“Singapore six, for your information now surface wind zero two zero at two four, gust four three, say intention,” the controller added.

“Gusting four three ah,” said Captain Foong. “Okay, okay, better, less,” he said.

“Less, less gust already,” relief pilot Ng agreed. Conditions seemed to be improving momentarily, which was a good portent for their takeoff.

As they continued inching slowly down taxiway NP, First Officer Latiff reminded his captain, “Next one is November one.”

“Okay, second right,” said Captain Foong.

“Second right, that’s right,” Latiff agreed.

Moments later, the plane neared the end of taxiway NP, so Foong said, “Tell them we are ready, lah.”

“Singapore six, ready,” Latiff said over the radio.

“Singapore six, roger, runway zero five left, taxi into position and hold,” the controller replied.

“Taxi into position and hold, Singapore six,” Latiff acknowledged. Picking up the public address system, he then ordered the flight attendants to their stations for takeoff.

“Singapore six, runway zero five left, cleared for takeoff,” said the controller.

At that moment they rolled past the hold short line for runway 05R, which was painted on taxiway NP, and began the right turn onto taxiway N1, which led to the thresholds of both runways 05R and 05L. The pilots finished the final checklist items, and First Officer Latiff called out, “Before takeoff checklist complete.”

“It going to be very slippery, I am going to slow down a bit, slow turn here,” Captain Foong added.

Continuing through the turn, he followed the arc of the green taxiway lights to the right, through N1 and across the white “piano key” markings at the threshold of the runway. As they maneuvered into position, the runway stretched out before them, vanishing away into a black void of rain.

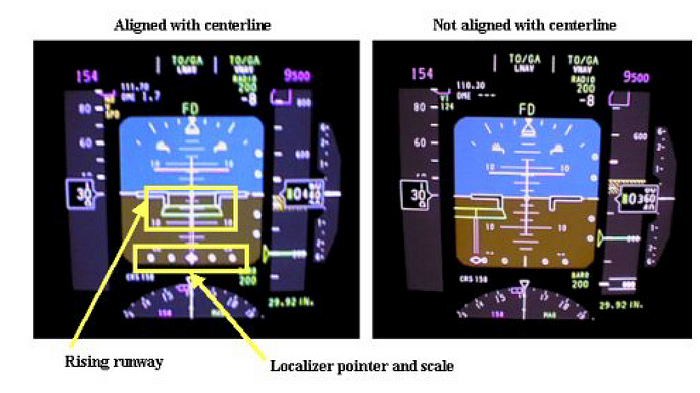

At that moment, First Officer Latiff noticed something odd. “And the PVD hasn’t lined up, ah,” he said, voicing his observation.

The para-visual displays, or PVDs, were an optional feature on the Boeing 747–400 that was not in widespread use, but had been installed by Singapore Airlines and a few other carriers. Located near the bottom outboard corner of each pilot’s windscreen, the small mechanical displays used the signals from a runway’s localizer equipment to help pilots judge whether they were properly lined up with the runway during a low-visibility takeoff. The PVDs are normally covered by a shutter, but when the plane moves within range of the localizer, which generates a signal in line with the runway axis, the shutters open, revealing a striped, rotating barber pole. If the barber pole appears to rotate left, for instance, then the localizer is to the left of the plane. On the other hand, when the barber pole stops moving, that means the plane is properly aligned with the runway.

In this case, the pilots had already programmed in the frequency for the localizer on runway 05L, so the PVDs should have unshuttered and centered as soon as they moved onto the runway. But to First Officer Latiff’s surprise, the shutters over the PVDs had not opened. This could have any number of meanings, including that they were not aligned with the runway, or that the localizer frequency had not been entered correctly. In this case, since they were still finishing the turn, Captain Foong simply said, “Yeah, we gotta line up first.”

“We need forty five degrees,” said relief pilot Ng, reminding Latiff that they needed to be within 45 degrees of the runway heading for the PVDs to unshutter.

Moments later, however, Captain Foong steered the plane into line with the runway centerline, and the PVD shutters still didn’t budge. “Not on yet, er, PVD,” he said. “Huh, never mind, we can see the runway, not so bad.”

Since the runway was clearly visible, and they were very obviously lined up with it, Captain Foong decided that the PVDs weren’t worth worrying about. After all, use of the PVDs was only required if the visibility was less than 50 meters, and since the runway visibility range that night was fluctuating between 450 and 650 meters, the PVD indications were advisory only.

At that moment, the cabin crew reported ready, so the pilots each confirmed the takeoff thrust setting, then advanced the thrust levers to takeoff power. The engines spooled up, the plane lurched into motion, and just like that, flight 006 was away — her pilots completely unaware that they were speeding blindly into the jaws of disaster.

◊◊◊

Although no one knew it yet, their mistake was infuriatingly simple: the runway they had turned onto was not 05L, but the parallel, closed runway 05R. After turning onto taxiway N1, Captain Foong should have taxied straight ahead for about 300 meters before turning right onto 05L, but instead, he made an immediate turn onto the much nearer runway 05R without ever straightening out. That was why the PVDs didn’t unshutter: they were simply outside the operating area of the localizer for runway 05L. Tragically, however, the pilots never pursued this odd little discrepancy — and now it was too late.

Unable to see the lighted construction equipment through the driving rain, they continued blithely onward, accelerating into the storm.

Relief pilot Ng called out, “Eighty knots,” and First Officer Latiff acknowledged.

“Okay, my control,” Captain Foong announced, and Latiff took his hand off the throttles.

“V1,” Latiff called out. It was no longer possible to abort the takeoff.

“V1,” Ng confirmed.

Suddenly, just before the call to “rotate,” Captain Foong spotted an object, directly in their path. He just barely had time to shout, “Something there!” And then the crash began.

Traveling at near takeoff speed, the 747’s landing gear clipped a concrete jersey barrier and a pit in the runway, ripping off several bogies; at almost the same moment, the plane plowed into an excavator, which rolled under the left wing and was thrown up into the tail, severing the left horizontal stabilizer. Shuddering from the heavy impact, the fuselage crashed to the ground, whereupon the two left engines collided with a pile of steel rebar, causing the entire plane to slew hard to the left, skidding sideways down the runway with its right wing down. The #3 engine was then ripped off and hurled toward the terminal building, while the back of the plane slammed into two parked steamrollers, tearing the fuselage in half just aft of the wings. Fuel escaping from the wing tanks ignited into a huge fireball as the crippled plane continued down the runway, rotating counterclockwise as it went, until it was sliding completely backwards with its tail into the howling wind. Finally, the right wing clipped a concrete pad, severing the #4 engine, and the forward fuselage spun around one final time before sliding to a stop, engulfed in flames. Nearby, the tail section skidded to a halt on its left side, rotated 90 degrees from the runway, coming to rest just outside the vast, burning pool of liberated fuel.

In the tower, the local controller heard a boom and saw a huge fireball on the runway. Realizing that the Singapore Airlines jet had crashed, he activated the crash alarm, and firefighters immediately rushed to the scene.

What they encountered there was downright apocalyptic. In the main deck cabin above the wings, almost everyone burned to death within moments, many without even a chance to leave their seats, as the massive fuel-fed fire came roaring in through the break in the fuselage. Farther forward, most of the first class and business class passengers in the nose managed to escape through the forward exit doors, but some were killed as dense smoke rapidly filled the plane, making it impossible to breathe. And in the upper deck, home to the cockpit and several additional business class seats, the fight for survival was especially brutal, as smoke, propelled by the chimney effect, rose up the stairwell and filled the cabin. Someone managed to open the left upper deck door, deploying the emergency slide, but it was soon damaged by fire and high winds, forcing others to climb down its tattered remnants. Among the last to leave were the three pilots, who were shaken but mostly unharmed, along with two flight attendants and seven passengers. Twelve other passengers and a third flight attendant never escaped the upper deck, and perished in the flames.

In the tail section, which came to rest some distance away, the absence of fire proved a blessing. Although the cabin was heavily damaged, with baggage and furnishings lying strewn through the aisles like the aftermath of a tornado, all 54 passengers and crew seated in this section had survived the crash. With the cabin turned completely on its side, escape was difficult; those seated on the right side often fell all the way across the cabin when they undid their seat belts, and two flight attendants were momentarily trapped after emergency escape slides, pressed up against the ground, inflated backwards into the cabin. It was also impossible to open any of the exit doors: on the left side, the ground was in the way, while no one could reach the right side, which was high up in the air. Instead, people near the front began calling others toward the break in the fuselage, through which they escaped, and by most accounts everyone had already left and was running for the terminal by the time firefighters arrived.

Although rescue teams reached the plane within three minutes, by that point most of the center section was fully ablaze, and firefighters were only able to get far enough into the plane to save three badly burned passengers in the vicinity of door 1L. One first responder also recalled encountering a pilot, shaken and desperate, pleading with him to save passengers who were still aboard, but there was little that could be done. Even basic rescue efforts were severely hampered by the powerful typhoon winds, which eventually became so strong that they actually rolled the entire tail section upright and spun it 90 degrees, like a massive weathercock. Also contributing to the dysfunction was the lack of a clear emergency medical plan, which led to the absence of a triage process and delays administering medical care.

By the time the fire was out and the injured had been taken to hospital, word of the crash was already beginning to reach international news media. Singapore Airlines moved quickly to dispel “rumors” that anyone had died in the crash, even as incredulous survivors, interviewed on live television, reported seeing people die before their very eyes. Indeed, the airline was soon forced to walk back its statements when authorities reported that dozens were unaccounted for. Hours later, the grim figures were made public: out of the 179 people on board, 81 had died, including 77 passengers and four flight attendants. Two more passengers died in hospital a short while later, bringing the final death toll to 83, while 96 others survived.

The crash ended 28 years of fatality free operations for Singapore Airlines, shocked the tiny country, and sowed doubt in the minds of air travelers around the world. After all, if such a crash could happen at one of the world’s best airlines, was anyone truly safe? This question made it all the more important that Taiwan’s independent accident investigation agency, the Aviation Safety Council (ASC), lead a thorough and unbiased inquiry into the causes of the disaster.

Initial speculation centered on the possibility that high winds associated with typhoon Xangsane had caused the plane to crash, but Singapore Airlines insisted that the winds at the time of the accident were within the limits for takeoff, and the ASC soon confirmed this. Furthermore, Captain Foong told investigators and company personnel that he saw an object on the runway just before the crash. At the same time, observers could not help but notice that photos of the scene appeared to prove that the wreckage was on the closed runway 05R, rather than the active runway 05L. As speculation mounted that the plane might have tried to take off from the wrong runway, Singapore Airlines issued an impassioned denial, arguing that such a well-regarded crew could not possibly have made such a mistake. Surely there must be another explanation — perhaps the plane collided with something on runway 05L, then slid out of control onto 05R. But ASC investigators soon found markings proving that flight 006 was on runway 05R the whole time, and the flight data recorder confirmed this, forcing Singapore Airlines to reverse course and issue a stunning admission of guilt.

The pilots’ experience, above average records, and conscientious decision-making made this discovery difficult to understand. The cockpit voice recording showed that they took numerous prudent precautions, from taxiing slowly to double-checking the crosswinds to discussing contingencies in the event of an emergency. Furthermore, another plane took off normally from runway 05L just 10 minutes earlier, and the runway was properly lit at the time of the crash. The visibility was reduced due to darkness and rain, but it was still perfectly possible to see where one was going. The pilots also knew that runway 05R was closed, and that they were supposed to take off on runway 05L; in fact First Officer Latiff had read back the runway number correctly just moments before the crash. But while all these facts initially made the error look inexplicable, as investigators dived deeper into the circumstances of the accident, a whole host of evidence began to emerge which painted the flight crew’s mistake in an entirely new light.

In his interview, Captain Foong, who was steering the plane, reported that he simply followed the green taxiway centerline lights onto the runway, which appeared to be the most obvious path, and that he never saw any centerline lights continuing further ahead to runway 05L. Consequently, he believed he had already reached the correct runway.

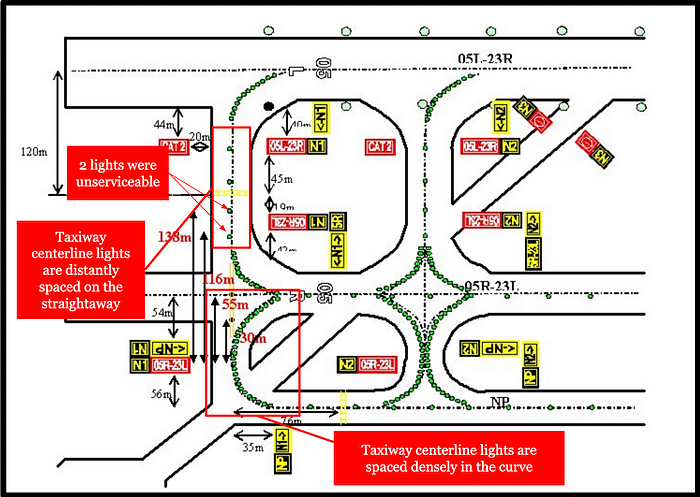

An examination of the taxiway lighting at the intersection of taxiway N1 and the head of runway 05R showed that there was merit to his interpretation. Taxiways are normally demarcated with green centerline lights, with curved branches leading to the runway centerline in order to help pilots line up. But in this case, the lights in the curve leading from taxiway N1 onto runway 05R were spaced 7.5 meters apart, while the lights on the straight portions of N1 were spaced 30 meters part, which was wider than allowed under International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) rules. As a result, the curve onto the runway was very prominent, but the centerline leading straight ahead was not. There were no centerline lights leading across the white “piano key” markings at the runway threshold, and while they did resume on the far side, there were only four additional lights before the curve onto runway 05L, some 200 meters distant. Under ICAO rules, there should have been 16 centerline lights in this area. Furthermore, investigators found that one of the four lights was unserviceable and another was unacceptably dim, making the path to runway 05L even harder to see.

The fact that the taxiway lighting layout was misleading had actually been noticed before. After the accident, the pilot of an MD-11 cargo plane that took off from runway 05L at Chiang Kai-shek Airport eight days before the crash reported to investigators that he had been misled by the taxiway centerline lighting. As he was taxiing along N1 toward runway 05L in dark and rainy conditions, he said he felt “compelled” to turn right onto runway 05R because of the relative prominence of the centerline lights leading onto that runway, compared to the centerline lights leading straight ahead. However, he realized that this was not the correct runway because there were no touchdown zone lights (these are only installed on runways intended for use in poor visibility, which 05R was not); because the runway was too narrow; and because the runway centerline lights were green, like a taxiway, instead of white.

Indeed, because runway 05R started life as a taxiway, its centerline lights were green, and always had been, while a runway’s centerline lights are normally white. This was one clue which could have alerted the pilots to the fact that they were on the wrong runway, but there were plenty of others as well. For one, just before the turn, a sign reading “05R” would have been visible, followed shortly thereafter by the name “05R” painted in white on the runway surface. Additionally, the sign for 05L should also have been visible in the distance during the turn, indicating that the correct runway lay farther ahead. However, all of these signs would no longer have been visible by the time the plane lined up with the runway, because they were all either behind the cockpit or underneath it.

Nevertheless, the cockpit itself contained several other indications that they were in the wrong place. In addition to the failure of the PVDs to unshutter, a small magenta diamond on the pilots’ primary flight displays, or PFDs, would have shown that the localizer was far to their left, and the runway symbol, normally in the center of the display, would also have been pushed all the way against the far left side of the screen, as shown below.

How could the pilots have missed or disregarded all of these potentially salient clues? Several factors likely contributed, but it’s worth noting first of all that humans tend to judge whether a situation looks “wrong” based on what we’re expecting to see, rather than objectively analyzing whether everything that should be there is in fact present. All three pilots told the ASC that they expected the closed runway to be unlit, barricaded off, and/or marked with a large “X” in front of the threshold. So when they turned onto runway 05R, which was either partially or totally lit (more on that in a moment) and did not have any signs or markings indicating its closure, it could have looked more like their mental picture of an active runway than their mental picture of a closed runway, even though its actual appearance differed from that of runway 05L in several key respects.

This effect would have been even stronger if the runway edge lighting was active, but on this matter there was a great deal of conflicting evidence. Although the edge lights should not have been turned on, since 05R was not being used as a runway, some witnesses, including Captain Foong, reported that the lighting was active. On the other hand, the edge lights did not appear on security camera footage at the time of the accident. Metallurgical analysis of runway 05R edge lighting wires that were broken during or after the accident revealed evidence of arcing, indicating that they were powered on at some point, but this could have occurred when rescuers asked controllers to turn on all the runway lighting about 40 minutes after the crash so that they could see what they were doing. The question of whether the edge lights were on was therefore never resolved, and in the end the Singaporean team members came to believe that they were illuminated, while the Taiwanese investigators disagreed. In any case, if the edge lights were on, the appearance that 05R was an active runway would have been greatly reinforced.

Having learned all of this, the picture of what happened becomes a lot clearer. Approaching the intersection of taxiway N1 and runway 05R, the lights leading onto runway 05R overpowered the widely spaced and unserviceable lights leading straight ahead, causing Captain Foong to instinctively turn onto the runway. Although signs and markings specifying that this was runway 05R were visible during the turn, they soon passed out of view. Once in position, the crew saw a runway with no closure markings or barricades, with illuminated centerline lighting and possibly illuminated edge lighting. The PVDs failed to unshutter, but the pilots’ knowledge of the rarely used PVD system was probably not sufficient to appreciate the significance of this issue. And although the pilots’ primary flight displays showed that the runway was to their left, they must not have looked at them.

Taken together, there were plenty of cues that this was not the right runway, but there were also several cues suggesting that it was. The fact that the pilots assimilated certain cues, but not others, makes this a classic case of that most human of failings: confirmation bias. When confronted with a small amount of initial information about a situation — such as the salient taxiway lighting — we tend to develop a mental model which may or may not correspond to reality. Then, once a model is in place, the brain unconsciously seeks out information that confirms our conception of the situation, while excluding information that contradicts it. Consequently, it’s possible that once Captain Foong started the turn, believing that he was turning onto runway 05L, his brain simply stopped processing cues that indicated otherwise. At any moment, something could have slipped through the filter and caused him to snap back to reality, but tragically, nothing did.

The other crewmembers could in theory have noticed the error and brought it to the Captain’s attention, but their opportunities to have detected the mistake were limited, because both had their attention fixed inside the cockpit during the turn. First Officer Latiff was finishing the before takeoff checklist and monitoring their taxi speed, while relief pilot Ng, having just heard a new weather transmission, was recalculating the crosswind component in order to double check that it was safe to depart (which it was). By the time either pilot looked outside the plane, they were already aligning with the runway, and the picture they saw didn’t look wrong enough for them to question it.

This fact allows us to segue into a fundamental conclusion about the nature of this accident: namely, that there was no procedural guard against a pilot taking off on the wrong runway, only an assumption that they would notice the “wrongness.” Signs, markings, and lights are helpful, but won’t save a pilot who doesn’t see them. On the other hand, even after missing all of these signs, a simple required procedural check — “Confirm takeoff runway” — could have prompted the pilots to look for that “wrongness,” at which point they might have seen it. At that time, however, procedural confirmation that the plane was on the correct runway was not widely required in the aviation industry, and no such procedure was in use at Singapore Airlines, or at most other companies. Instead, the crew of flight 006 was able to line up with the wrong runway without having violated or omitted any required procedures, except of course for the very basic implicit commandment, “thou shalt line up with the correct runway,” which is about as meaningful a safety procedure as “thou shalt not crash.”

◊◊◊

In any field involving humans, achieving the highest possible level of safety requires that barriers be erected to prevent human errors from leading to disaster, because the expectation that humans will perform perfectly in every case is fatally flawed. Certainly one would expect pilots of Singapore Airlines caliber to line up with the correct runway 999,999 times out of a million, but that 1 in a million only has to happen once to leave 83 people dead and others with lifelong injuries. Furthermore, with the volume of flights being carried out 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, for year after year, that small chance eventually becomes an inevitability, unless redundancy is added to the system. In this case, redundancy could mean a mandatory check that the plane is on the correct runway, but no regulations requiring such a check existed. On the other hand, a barrier could be physical — and this is where investigators began to criticize the entire idea behind the partial closure of runway 05R on the night of the accident.

The basic problem was that 05R maintained many features of a runway, including “piano keys,” a runway number, and runway lighting. Furthermore, the decision to keep the ends open for use as a taxiway meant that physical barriers to entry onto the closed runway could not be erected, and some lights would remain illuminated, leaving few direct clues that the runway was closed. And yet, under conditions of restricted visibility, the construction equipment would not be visible until an attempted takeoff was too far advanced to abort. As a result, a competent risk analysis could have raised the possibility of a crash like that of flight 006 before any such crash actually happened. Steps to mitigate the risk could then have been taken, such as the emplacement of temporary signs or markings at the runway threshold.

Although Taiwan’s ASC didn’t question the decision to keep the runway open as a taxiway, the Singaporean delegation did. In their comments on the report, the Singaporean experts pointed out that at the time of the accident, there was no intention to ever use runway 05R/23L as a runway again, which meant that it was by definition a “permanently closed runway.” Under ICAO rules, permanently closed runways must have their runway identification markings (such as piano keys, runway numbers, and runway lighting) removed. On the other hand, the assumption made by the Taiwanese team appears to have been that because the official re-designation had not yet been handed down, 05R/23L was technically still a runway, and that there was no requirement to remove the runway markings, even though there was also no plan to let planes actually use the runway for normal runway things.

In the Singaporeans’ view, this interpretation of the rules was myopic and did little more than lay the groundwork for disaster, and I tend to agree. It’s just not that hard to imagine why leaving both ends of a runway open while barricading the middle would be potentially dangerous. But we should also be careful to remind ourselves that we’re looking back on this with the benefit of hindsight.

◊◊◊

In the end, Singaporean and Taiwanese investigators did not agree on how exactly to weight all the contributing factors leading up to the accident. This article so far has presented only those factors whose importance was accepted by both teams, except where otherwise indicated. Both groups also attempted to identify other potential factors, many of which would require descending down a rabbit hole of systemic risk with little to no direct connection with the accident, but those aspects are mostly beyond the scope of this article. Nevertheless, if you want to learn more, you can always read the ASC’s 508-page final report and appendices, as I did.

Overall, regardless of squabbles over details, the crash of Singapore Airlines flight 006 is a sobering example of the dangers presented by systems that are unforgiving of human error. It’s always better to create a system that forgives errors before they happen rather than forcing us to forgive them after the fact. Unfortunately, however, even after the circumstances of the crash were elucidated, the pilots received no such forgiveness. Captain Foong Chee Kong and First Officer Latiff Cyrano were held in Taiwan for several weeks under threat of criminal charges before being allowed to leave, and even then, their case continued in absentia. In May 2002, manslaughter charges were filed against them, but these were suspended indefinitely in July of that year, on account of the pilots’ exemplary records prior to the crash; their expression of remorse afterward; and the difficult conditions on the night of the accident. Nevertheless, Singapore Airlines fired both pilots concurrently with the suspension of the charges (while sparing relief pilot Ng Kheng Leng), eliciting condemnation from the Air Line Pilots Association, which called the move “harsh and inappropriate.” Indeed, what happened to them could just as easily have happened to someone else. Fortunately, another company recognized that, and both pilots finished their careers at AirAsia.

As a result of the accident, numerous changes were made, including new training at Singapore Airlines, new airport design regulations in Taiwan, increased airport inspections by the Taiwanese CAA, greater adoption of cockpit moving map displays and “takeoff runway disagree” warnings, and major renovations at Chiang Kai-shek Airport (now Taipei Taoyuan Airport) aimed at bringing the facilities up to international standards. New taxiway and runway markings were painted, the former runway 05R/23L was fully decommissioned, new centerline lights were installed on taxiway N1, and runway guard lights — flashing lights indicating the presence of an instrument runway — were installed on runway 05L/23R (now simply runway 05/23). The guard lights were an especially galling omission, since ICAO rules required them, and their conspicuous presence might well have alerted the crew of flight 006 to the location of runway 05L. But what’s done is done, and at least now the airport has them, as it should have all along.

◊◊◊

Although lessons were learned and improvements were made, the prevention of runway incursions — the entry of an aircraft into an incorrect runway — remains a top priority for safety authorities around the world. Near collisions between taxiing, departing, and/or landing aircraft are still a major point of concern, and some of the closest calls in recent years have involved similar flight crew errors, including the infamous near crash of Air Canada flight 759, which almost landed on an occupied taxiway at San Francisco International Airport in 2017. While the current aviation system is incredibly safe, safer than most experts of past decades could even have imagined, these incidents show that the risk is not zero, and the fate of Singapore Airlines flight 006 should remind us that even well-trained pilots at world class airlines can’t afford to let their guard down. After all, sometimes even the best among us will make the simplest of mistakes, and it never hurts to double check the seemingly obvious when lives are on the line.

_______________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit

Support me on Patreon (Note: I do not earn money from views on Medium!)

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 240 similar articles

_______________________________________________________________

Note: this accident was previously featured in episode 50 of the plane crash series on August 18th, 2018, prior to the series’ arrival on Medium. This article is written without reference to and supersedes the original.