Value for Money: The crash of ValuJet flight 592

Note: this accident was previously featured in episode 28 of the plane crash series on March 17th, 2018, prior to the series’ arrival on Medium. This article is written without reference to and supersedes the original.

On the 11th of May 1996, the pilot of a fully loaded DC-9 reported smoke in the cabin shortly after takeoff from Miami, Florida. Moments later, as it turned back toward the airport, the airliner vanished from radar, spiraling down through the bright spring sky until it slammed into the turbid waters of the Everglades, taking with it the lives of 110 passengers and crew. The crash cast an ominous pall over the unchecked growth of the low cost airline industry, whose sudden appearance had raised safety questions even before the devastating crash. The plane that went down belonged to the worst offender of them all: ValuJet, an ultra-low-cost airline known for its no-frills service, blue and white airplanes, and constant mechanical breakdowns. Investigators would find that ValuJet flight 592 was consumed in the air by an unstoppable fire that produced its own oxygen, a terrifying conflagration made possible by a gross breach of logistics protocol by one of ValuJet’s numerous contractors. As the public learned how ValuJet sidelined safety in the pursuit of growth, and how red flags were ignored, the consequences exploded outward into the industry at large, toppling some of the highest figures in America’s aviation industry. The crash would ultimately assume a place as one of the most influential in US history, as an example of the depths to which the system can fall when profit is the only goal and those at the bottom of the ladder are left to find their way in the dark.

◊◊◊

On October 26th, 1993, a new airline took to the skies for the first time, launching an aging Douglas DC-9 from the runway in Atlanta, Georgia, propelled by the promise to get its passengers to their destination more cheaply than anyone else. The airline, whose founders had granted it the vaguely unsettling name ValuJet, represented something radically new in the American aviation industry: an air carrier whose sole attraction was its low ticket prices, which served to lure record numbers of passengers despite its old, noisy airplanes and lack of in-flight services. The model proved to be such a success that ValuJet was soon able to boast of the shortest time from launch to profitability of any new US airline ever. These profits were quickly poured back into an aggressive campaign of expansion as ValuJet’s management sought to buy as many used DC-9s as they could find. By December 1994 it had increased the size of its fleet from two DC-9s to 22, which then more than doubled to 48 by the end of 1995, just two years after its founding. Seemingly overnight, ValuJet’s blue-and-white airplanes with their smiling cartoon character logo had become a ubiquitous sight at airports across the southeastern United States.

Internally, ValuJet was something of a mess. It was no secret that the airline had been a money-making venture from the start, and a remarkably successful one. One of the company’s co-founders, Robert Priddy, had already left a trail of successful regional airlines in his wake, including Atlantic Southeast and Air Midwest, and he is said to have launched ValuJet in Georgia and Florida simply because this part of the country occupied a sweet spot where demand was plentiful and wages were low. The latter especially was one of several ways in which ValuJet achieved its extraordinary profitability. Company executives bragged to Wall Street investors about paying their employees below market rates. Pilots, many of them desperate for work after waves of layoffs at major carriers, were forced to pay for their own training, only to be offered bargain basement salaries in return. Flight Attendants were required to join the airline through a staffing agency owned by ValuJet President Lewis Jordan’s ex-wife and daughter. And allegations were made that ValuJet paid mechanics less money if they failed to finish repair work on time.

An equally significant part of ValuJet’s business model was its effort to outsource all the most expensive aspects of operating an airline. ValuJet became the industry’s most prolific signer of third-party service contracts, covering practically every stage of operation except the actual act of flying the airplanes. ValuJet’s in-house maintenance capabilities, for example, did not extend beyond routine service checkups; instead, it maintained contracts with no less than 21 different repair stations to which it delegated all non-routine maintenance and heavy inspections. Some of these contractors in turn subcontracted these tasks out to a still-murkier network of even more third-party repair stations. The result was a mess of overlapping responsibilities that no one at the airline fully understood. A senior vice president of operations at the company would later testify that they were growing too fast to keep track of their own activities, and that the Director of Quality Assurance and Maintenance was “in way over his head.” By the spring of 1996 these warnings had apparently made their way to the very top, as ValuJet’s executives reluctantly decided to suspend further growth for a year or so to let the airline’s still-untested organizational structure catch up.

With the public at large, ValuJet quickly gained a reputation for shoddy service and frequent mechanical breakdowns. Scrutiny became especially intense following a 1995 incident in which a ValuJet DC-9 burst into flames and filled with smoke following an engine failure on the runway in Atlanta. Seven people were injured, one of them seriously. By the spring of 1996 the airline’s reputation had gotten so bad that President Jordan had to hold a special press conference in which he emphasized that ValuJet was a “safe airline” which had “never had a fatality,” whatever small comfort that was after just two and a half years of operation. In any case, the bookings kept coming. The low prices were simply too good to resist.

◊◊◊

In January 1996, ValuJet agreed to purchase two McDonnell Douglas MD-82 aircraft and an MD-83 which had been retired by major carriers and returned to the manufacturer. Before they could be pressed into service, the MD-80s needed to be overhauled to ensure that they were configured to ValuJet standards and that all their systems were in good working order. Given its business model, ValuJet obviously had no plans to do this itself, and the task of overhauling the jets was delegated to one of its three heavy maintenance contractors: a designated Part 145 repair station known as SabreTech, which operated a maintenance facility on the grounds of Miami International Airport. The planes were ferried to the facility in February, at which point SabreTech began a mammoth effort to get them ready before ValuJet’s imposed deadline in late April. The process would ultimately involve 587 people, of whom about three quarters were subcontractors who did not work directly for SabreTech.

One of the numerous tasks that had to be carried out was to check the serviceability of the oxygen generators which supplied the passenger oxygen masks.

Airliners use a variety of systems to supply oxygen to passengers in an emergency, but the method employed by the McDonnell Douglas MD-80 series involved the use of so-called chemical oxygen generators. Each passenger service unit on the MD-80, which includes the drop-down mask assembly as well as the reading lights, fasten seatbelt signs, and so on, contains a built-in oxygen generator which supplies either two, three, or four oxygen masks, depending on the exact model. When a passenger pulls down on the mask to put it on, the pull force is transferred to a lanyard which withdraws a retaining pin holding back a spring-activated hammer. Once the pin is removed, the hammer slams against a percussion cap, triggering a small explosive charge. The explosion in turn releases energy which heats the generator’s sodium chlorate (NaClO3) core to its decomposition temperature. Upon reaching this temperature, the sodium chlorate progressively decomposes into sodium chloride (NaCl) and oxygen (O2). The oxygen then flows out through a filter and into the passenger masks, providing between 12 and 20 minutes of breathable oxygen in an emergency.

On the off chance that you remember anything from high school chemistry, you might recall that this reaction is exothermic — that is, it produces heat as a byproduct. In fact, when activated, the surface of the small cylindrical oxygen generators can reach temperatures of 230–260˚C (450–500˚F), sufficient to cause serious injury when touched and even to ignite nearby flammable materials. For this reason, oxygen generators are mounted within specialized heat shields above the passenger service units, and are equipped with warning labels informing users that they can generate intense heat.

Because the reliability of the generators decreases with age, they are limited to a 12-year service life, after which they must be removed and disposed of. Upon inspection, SabreTech found that most of the oxygen generators on two of the three ValuJet MD-80s were more than 12 years old, so it ordered replacements and began systematically removing the expired devices. This process would ultimately require several weeks to complete and would involve 910 hours of labor by 72 different people. The exact number of oxygen generators removed from the two planes was not recorded, but mechanics later estimated it to be about 144, of which 138 were still perfectly capable of producing oxygen.

In order to accomplish this work, SabreTech mechanics referred to a work card, furnished by ValuJet, which provided step-by-step instructions for the removal of the generators. The mechanics would have followed these instructions closely, because none of them had swapped out an airplane’s oxygen generators before. They were for the most part aware of why the generators were being removed, and that they generated heat, but the task was not particularly interesting or unusual. Some of the mechanics apparently set off a few generators just to see what would happen, but they mostly sat on the floor making a faint hissing sound. Definitely not anything to write home about.

The work card, designated #0069, included a step which read, “If generator has not been expended, install shipping cap on firing pin.” Such a cap, variously referred to in the documentation as a shipping cap or safety cap, physically prevents the hammer from contacting the percussion cap and triggering the device, even if the retaining (firing) pin is removed. But when the mechanics asked about the caps, they were told that SabreTech had none. According to the contract between ValuJet and SabreTech, so-called “peculiar expendables” — highly specialized single-use items like safety caps — should have been supplied by ValuJet, but for whatever reason the airline had failed to do so.

The mechanics would later prove unable to keep a straight story regarding the lack of safety caps. One mechanic said he asked his supervisor whether they had any, and was told that the answer was no. The supervisor denied that the conversation took place, or that he was aware of the need for safety caps. Another mechanic claimed that the idea of taking the safety caps off the new generators was discussed, only to be rejected because the installation instructions clearly stated that the caps could not be removed until the units were checked out as fit for service. The SabreTech project manager also denied any knowledge of the safety cap issue. In any case, the mechanics made do without. Some of them wrapped the lanyards around the generators and then taped them in place; others cut the lanyards short, believing this would make activation less likely; and a few just left the generators as they were. In the end, they all went to the same place, which turned out to be five cardboard boxes on a shelf in the workshop.

On May 5th, the overhaul was completed, and a SabreTech inspector signed off on the general work cards for each of the three ValuJet airplanes, certifying that all requisite tasks had been completed. He knew that work card 0069 called for safety caps on the oxygen generators, and that no safety caps had actually been installed, but his supervisor assured him that this issue would be rectified by SabreTech’s storage and spare parts department (known on the workshop floor as “stores”). Apparently convinced by this vague promise, he gave the work card his signature, despite knowing that the work was not done.

Shortly after the completion of the task, a ValuJet technical representative on site at SabreTech’s Miami facility noticed the boxes of oxygen generators and asked that they be moved farther away from the airplanes, presumably because they presented a fire hazard. Two SabreTech mechanics subsequently took the boxes to the facility’s shipping and receiving area, where ValuJet company materials were stored. Naturally, anything that had come off a ValuJet plane still belonged to ValuJet, and generally such materials did not stay at SabreTech for long, so the shipping area was considered a reasonable place to put them. Nevertheless, it was unclear who ordered that the oxygen generators be placed there.

When the mechanics arrived at the shipping area, no one was present, so they simply dropped off the boxes and left. There was no requirement to tell anyone what was in them.

On the 7th or 8th of May, SabreTech’s director of logistics instructed the shipping clerk to clean up the shipping and receiving area in anticipation of an inspection by a potential customer. The director of logistics was well aware that a previous customer had described the “housekeeping” in this area as “unacceptable,” and he was keen to avoid another embarrassing audit.

The shipping clerk apparently asked whether he could send the ValuJet company material back to ValuJet headquarters in Atlanta, to which the director of logistics allegedly replied, “Okay,” although he would later deny this. The director of logistics claimed that he expected someone from ValuJet to come down from Atlanta on May 9th or 10th to deal with the ValuJet company material, but when one of the ValuJet representatives at SabreTech called the company’s Atlanta storeroom to arrange a visit, he was told that they would not be able to send anyone until Monday the 13th. It remains uncertain whether the director of logistics decided to grant permission to send the materials back to ValuJet without ValuJet’s permission, or whether the shipping clerk simply misheard his instructions.

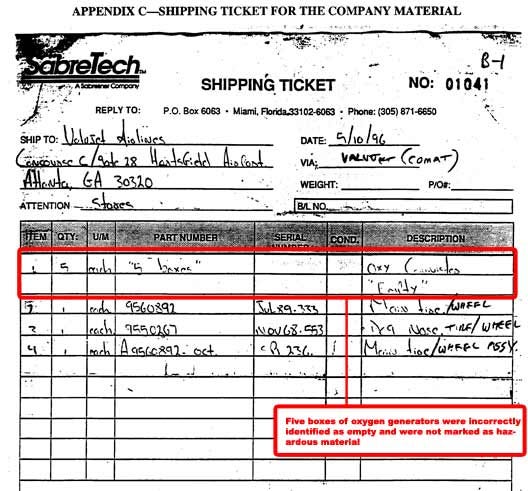

In any case, the shipping clerk repacked the boxes of oxygen generators, placed several centimeters of bubble wrap in the top, and sealed them up for shipment. On May 9th, he instructed the receiving clerk to write up a shipping ticket for the boxes, which he described as containing “empty oxygen canisters,” along with three aircraft wheels and tires which also belonged to ValuJet. The receiving clerk hadn’t looked inside the boxes and had no reason to disbelieve the shipping clerk, so on the shipping ticket he wrote that the boxes contained, “Oxy Canisters — ‘Empty’.”

Somewhere here, a crucial misunderstanding had occurred, because the contents of the boxes were not oxygen canisters, nor were they empty. The shipping clerk, not being a trained mechanic, apparently made his own judgment about what was in the boxes based on the tags that the mechanics had attached to the generators. Each generator had a green tag, which normally meant “repairable” (although they were not repairable at all), on which the mechanics had variously written, “expired,” “outdated,” or “out of date.” The shipping clerk didn’t know what an oxygen generator was, so he apparently guessed that the cylindrical objects were oxygen “canisters” — not a real term for any object on an airplane — and that the objects probably once contained oxygen, but did not anymore. Otherwise, he must have surmised, why would they have been removed if there was still oxygen in them? And perhaps he may have thought the “repairable” tags indicated that they simply needed to be refilled before they could be returned to service.

We cannot know for sure that this was his exact thought process. But whatever it was that led him to morph “expired oxygen generators” into “empty oxygen canisters” would play a central role in a deadly sequence of events which was already accelerating toward disaster.

On May 11th, the boxes of oxygen generators and the three aircraft tires were loaded into a truck and driven to the ValuJet cargo loading ramp at Miami International Airport. A ValuJet cargo handler signed off on the shipment, which was taken to a ValuJet DC-9, registration N904VJ, scheduled to depart shortly for Atlanta. He showed the cargo manifest to the first officer, who, seeing nothing suspicious, signed off on it without hesitation. The cargo handler then placed the largest of the three wheels in the forward cargo compartment, placed a smaller wheel on top of it, and arranged the boxes of oxygen generators around the edge. Around this crude pyramid he stacked several items of passenger baggage, 28 kilograms of US mail, and the third aircraft wheel, which he leaned up against one wall. He did not secure any of the cargo, nor was there any means to do so, because ValuJet’s policy was not to carry any cargo hazardous enough to require securement. By 13:40, all the cargo was on board, and the cargo doors had been closed. The flight to Atlanta had yet to depart the gate, but it was already doomed.

◊◊◊

ValuJet flight 592 from Miami to Atlanta was, as usual, almost fully booked. At the same time as the cargo was loaded below, up above, 105 passengers were busy filing on board, filling nearly every seat aboard the cramped DC-9. Overseeing the boarding process were three flight attendants, all of whom had worked for ValuJet for less than 18 months; two of them were only 22 years old.

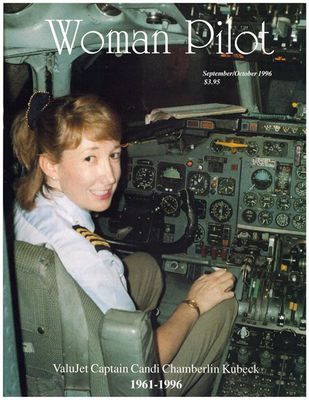

In command was Captain Candalyn “Candi” Kubeck, an experienced pilot who had signed on with ValuJet after her former employer, Eastern Airlines, abruptly went out of business in 1991. She had just turned 35 the day before the flight and was said to be looking forward to celebrating with her friends and family later that week. Her copilot, 52-year-old First Officer Richard Hazen, was even more experienced, having accumulated 11,800 hours throughout his career, which included stints as a military pilot and a civilian flight engineer before winding up, like Kubeck, at ValuJet. They both likely would have demurred if asked, but in general, experienced pilots like Kubeck and Hazen who were flying for ValuJet “wound up” there only after they had exhausted alternative options.

That day the pilots had to contend with numerous inoperative systems aboard the aging DC-9, which was manufactured in 1969, but given that most of ValuJet’s fleet was around that age, they were probably used to it. The autopilot had been placarded inoperative since May 10th, and the left fuel flow gauge wasn’t working either. The cabin interphone had failed during a flight into Atlanta on the day of the accident, and after arriving, their departure was delayed when an electrical fault popped the circuit breaker for the right auxiliary hydraulic pump. Although mechanics managed to solve the problem, the next flight from Atlanta to Miami was marred by the failure of the passenger address system, which forced the flight attendants to speak to the passengers using a megaphone. It was no wonder why ValuJet had a very public reputation for mechanical unreliability.

By 14:00, ValuJet flight 592 was making its way toward the runway, navigating the afternoon traffic on MIA’s crowded taxiways. Ahead of them, an American Airlines plane had lined up for takeoff, but had yet to roll. “That’s gotta be frustrating for those American guys,” said First Officer Hazen. “Have to wait for the company to give them their takeoff data.”

“I’d kinda like to have that problem,” Captain Kubeck said, taking a veiled swipe at her employer. Hazen chuckled.

“Critter 592, runway nine left, taxi into position and hold,” the controller announced, using ValuJet’s kitschy callsign. As the American Airlines plane climbed away, Kubeck maneuvered her DC-9 to the runway threshold, ready to follow.

Underneath the forward galley, in the depths of the forward cargo compartment, an oxygen generator clanked against its neighbor. The retaining pin fell away, and the hammer struck the percussion cap with a faint pop, followed by this hiss of escaping oxygen. The generator rapidly increased in temperature until it ignited the layer of bubble wrap, placed there by the shipping clerk. Within seconds the nascent flame spread to the cardboard box itself, heating more nearby oxygen generators, until their sodium chlorate cores also began to decompose. By the time the controller announced, “Critter 592, cleared for takeoff,” a deadly chain reaction was probably already underway.

Kubeck and Hazen would have had no way of knowing that a fire had broken out aboard their airplane, because the forward cargo compartment had no smoke detectors. Unaware of the terrible danger, Kubeck called out, “Set takeoff power.”

“Power is set,” Hazen replied.

Flight 592 accelerated down the runway, reaching decision speed in 28 seconds. Moments later, Captain Kubeck pulled back and lifted the plane off the runway, climbing away into the bright blue sky, from which none of her passengers and crew would return alive.

For the next six minutes, the flight seemed utterly routine. Everything that was working on departure was still working, and the pilots’ biggest concern was a thunderstorm in the far distance. And yet beneath their feet, the cargo compartment was already being consumed by a raging conflagration that threatened to destroy the plane from within. Inside the airtight compartment, the fire only continued to grow, becoming hotter and hotter as each newly tripped oxygen generator poured more and more oxygen onto the blaze.

Suddenly, at 14:10 and three seconds, a muffled explosion rocked the plane — one of the fully inflated aircraft tires in the cargo hold had given way under the intense heat. At that moment, the fire suddenly burst through the supposedly fire-resistant cargo compartment liner and began to chew through electrical wires like an insatiable monster.

“What was that?” Kubeck asked, suddenly alarmed.

“I don’t know,” Hazen replied.

Within seconds, multiple warning lights appeared, and several systems began to fail before their very eyes. “’Bout to lose a bus?” Kubeck said. “We got some electrical problem.”

“Yeah,” said Hazen. “The battery charger’s kicking in. Ooh, we gotta — ”

“We’re losing everything!” Kubeck exclaimed.

“Critter 592, contact Miami center on 132.45, so long,” the controller said, interjecting into the ongoing emergency.

Ignoring transmission, Kubeck said, “We need, we need to go back to Miami.”

At that exact moment, flames ripped upward through the cabin floor just aft of the forward galley, sending passengers running for their lives. The cockpit voice recorder picked up the sound of panicked shouting and a woman yelling, “Fire, fire, fire!”

“We’re on fire!” someone screamed. “We’re on fire!”

Just 24 seconds had passed since the explosion, and the situation was already out of control.

Unaware of the terror unfolding aboard flight 592, the controller repeated their instruction: “Critter 592, contact Miami center, 132.45.”

This time, Hazen did not hesitate to reply, “Uh, 592 needs immediate return to Miami.”

“Critter 592, roger, turn left heading 270, descend and maintain 7,000,” said the controller. “What kind of problem are you having?”

“Fire,” said Kubeck.

“Uh, smoke in the cockp — smoke in the cabin,” Hazen stuttered.

Kubeck had already put the plane into a descent from an altitude of 10,800 feet; now she began to turn it back to the airport. She attempted to reduce engine power to speed their descent, but the control cables were failing, and only the right engine rolled back.

In the cabin, one of the flight attendants attempted to contact the pilots via the interphone. “Okay, we need oxygen, we can’t get oxygen back there!” she said. But the interphone, which hadn’t been working since morning, was still dead. The shouting in the passenger cabin started to pick up again.

Giving up on the interphone, the flight attendant opened the cockpit door and said, “Completely on fire!” before slamming it shut again.

Somewhere in the back, a control cable snapped. The plane started to pitch up, leveling off momentarily at 9,500 feet, before Captain Kubeck managed to wrangle it back into a descent.

Calling air traffic control, First Officer Hazen hurriedly said, “Critter 592, we need the closest airport!”

“Critter 592, they [fire trucks] are gonna be standing by for you, you can plan runway 12 when able, direct to Dolphin now.”

Aboard the plane, the cockpit voice recorder abruptly stopped working. The flight data recorder followed fifteen seconds later. Air traffic control tapes captured First Officer Hazen requesting radar vectors to the airport, followed by silence. In fact, controllers would never hear from the stricken flight again.

For another minute and a half, flight 592 continued to fly, completely cut off from the world, caught within a nightmare from which there would be no escape. As the pilots fought for control of their dying jet, Miami radar captured the plane leveling off at 7,400 feet before suddenly plunging into a terrifying dive in excess of 12,000 feet per minute. In 30 seconds, it fell more than 6,400 feet, hurtling straight for the ground, seemingly out of control. And then, at a height of 900 feet, by some miracle it seemed to recover. Only a pilot could have done it, pulling the plane almost level just seconds before it would have hit the ground. For a brief moment it hung there between life and death, streaking low across the trackless mires, nearly on course for runway 12 at MIA. But the recovery was heartbreakingly brief. Seconds later, the plane rolled hard to the right, the nose fell through, and flight 592 plunged directly into the Everglades at more than 400 knots. A tremendous geyser of mud ascended high above the quaking reeds, paused, then fell back to earth as quickly as it rose. The DC-9 had seemingly vanished into the marsh, leaving only a yawning hole, stained black by jet fuel, to mark its passing.

◊◊◊

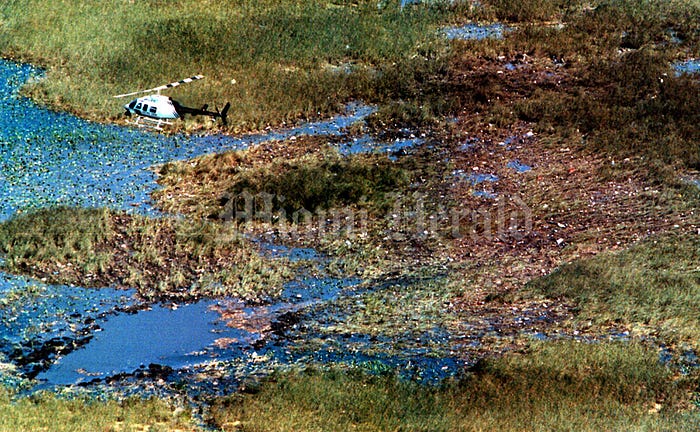

Although first responders rushed to the flight’s last known position, the scene upon their arrival crushed the hopes of even the most optimistic rescuers. Circling overhead in a helicopter, all that could be seen was a black hole in the sawgrass surrounded by tiny pieces of debris, strewn like confetti across the surface of the Everglades. Within minutes of their arrival, they reported back their grim discovery: of the 110 passengers and crew, there were no survivors.

The crash immediately captured the attention of the American public, and thrust the spotlight on ValuJet, a company which was already rumored to be unsafe. Had ValuJet’s poor maintenance caused the fire? What kind of fire could have brought down the plane just three and a half minutes after the first sign of trouble? Answering these swirling questions would be the responsibility of the National Transportation Safety Board, or NTSB.

The NTSB had encountered difficult investigations before, and some might have been more technically and scientifically challenging, but ValuJet flight 592 presented the most physically demanding crash scene in the agency’s history. Most of the plane was shattered into tiny pieces under a layer of water, sawgrass, and mud, which was soaked in jet fuel and infested with alligators and venomous snakes. The only way to recover the wreckage — and the remains of the victims — was to painstakingly comb through the marsh in full hazmat gear, picking out each piece of debris by hand, while snipers kept watch for alligators.

The search eventually turned up some, but nowhere near all, of the ValuJet DC-9. Although the black boxes were found intact, the same could not be said of the occupants. The human remains at the site consisted only of small pieces of flesh, many of which were too badly contaminated to permit any sort of testing. Even after months of work, pathologists were only able to positively identify remains belonging to 68 of the 110 victims. Autopsies were out of the question, so it remains unknown to this day whether those on board might have died of burning or smoke inhalation prior to impact. In grimly scientific terminology, the NTSB report would eventually explain that “a small amount of human tissue was identified as that of the first officer,” and that no trace of Captain Kubeck could be found at all. Did the pilots lose control because they inhaled smoke and became incapacitated? Without any remains, there was no way to know for sure.

By combining black box data, radar tracking data, wreckage patterns, and witness observations, the NTSB was able to construct a tentative sequence of events in the plane’s final moments. The apparently uncommanded level-off at 9,500 feet, and the failure of the left engine to roll back when ordered, showed that the controls were becoming unreliable. Heavy fire damage to the left side of the cabin floor, where the captain’s control cables were routed, suggested that fire may have burned through Captain Kubeck’s controls prior to impact. Since Kubeck was flying the plane, this could explain the sudden dive from 7,400 feet. But the fact that they pulled back out again could only mean that someone was still conscious and trying to fly the airplane, right up almost until the final moments of the flight. Investigators surmised that this might have been First Officer Hazen, whose control cables may have remained intact longer. Just seconds later, however, the plane rolled right and dived into the ground, indicating that control was lost almost as soon as it had been regained. This might have been because Hazen’s control cables also failed, or because the pilots were incapacitated by smoke within the last seven seconds of the flight. In either scenario, the plane would have banked to the right all on its own due to the asymmetric thrust from the engines.

The cause of the fire, while initially the subject of intense speculation, turned out to be more obvious than the investigators had probably expected. Burn patterns on the recovered debris showed that the probable ignition point lay inside the forward cargo compartment, ruling out an electrical cause. The cargo itself then came under scrutiny, and in particular the “empty oxygen canisters” described on the load manifest. The exact meaning of “oxygen canisters” was unclear — it couldn’t mean oxygen bottles, because fitting 144 of those into a DC-9 cargo hold was physically impossible — but recovery crews at the crash site were finding something disturbing: dozens of mangled oxygen generators, most of which appeared to have been activated. Because the DC-9 doesn’t use oxygen generators in its emergency passenger oxygen system, and therefore would not otherwise have had any on board, these could only have been the “oxygen canisters” indicated on the manifest. And to make matters worse, none of the generators had safety caps — something which was required merely to stow them on a shelf, let alone in the cargo hold of a passenger airplane.

The fire hazard posed by even a single improperly packaged oxygen generator is substantial. Previous incidents made that plain. In 1986, an American Trans Air DC-10 was destroyed by a fire at the gate after the passengers had disembarked; the NTSB traced the fire to a mechanic’s improper handling of an oxygen generator located in a passenger seat which was being transported as cargo. The seat had not been labeled as containing hazardous materials, despite containing an oxygen generator. This was but the most serious of a string of fires caused by oxygen generators, although thankfully the devices were so volatile when packaged improperly that they usually caught fire well before making their way onto an airplane.

But just how intense could such a fire become under the conditions of the accident flight? After interviewing the shipping clerk who packed the generators and the cargo handler who loaded them, the NTSB was able to ascertain the general environment surrounding the generators inside the cargo hold of flight 592. These conditions were then replicated inside a specialized fire testing facility. Two tests were conducted with only the cardboard box full of generators, while three were conducted with the full setup, including multiple boxes of generators, three aircraft tires, luggage, and mail. A single generator was then activated using a pull cord. In three out of five tests, this resulted in a serious fire without any help from the investigators, and in one of the full-scale tests the temperature of the fire reached a value of at least 1,760˚C in just 11 and a half minutes. The blaze’s actual maximum temperature could not be determined because 1,760˚C was as high as the thermometer went.

The reason for this volatility was simple enough: if one generator sparked a fire, the heat would initiate the oxidation reactions in nearby generators, providing the fire with more oxygen and causing it to spread to still more generators, and so on until everything had been consumed. ValuJet flight 592 stood as a stark example of the astonishing rapidity with which such a fire could destroy an airplane. In fact, only three minutes passed between the pilots’ discovery of the fire and the moment of impact.

The first indication of a problem was the explosion of a tire in the cargo hold, followed by cascading electrical failures. However, investigators noted that in their tests, it took 16 minutes for the fire to get hot enough to burst the first tire, while the explosion captured on the flight recorders occurred just six minutes after takeoff. That led to a disturbing question: did the fire actually start before takeoff, only to be unwittingly carried into the air?

The NTSB was quick to note that the actual fire could have intensified more quickly than its test blaze, which was not conducted within the confined, heat-trapping space of a cargo compartment. Nevertheless, it seemed unlikely that this would cut ten minutes off the time required to burst the tire. On the weight of probabilities alone, the NTSB considered it likely that the fire began when something jostled an oxygen generator after loading concluded at 13:40, perhaps during the subsequent taxi sequence, but certainly not later than the takeoff roll at 14:03. And that meant that if the DC-9’s forward cargo compartment had been equipped with a smoke detector, the pilots probably would not have attempted to take off in the first place. The plane could have been evacuated on the runway, and everyone almost certainly would have survived.

The idea that a cargo compartment on an airplane might not be equipped with a smoke detector seems insane in hindsight, but was in fact based on assumptions about fire behavior which did not account for events like ValuJet 592. At that time, and still today, cargo compartments were divided into several classes with different levels of fire protections. A Class A compartment is one in which a fire would be easily discovered and extinguished by a crewmember. A Class B compartment is one which requires an alarm to alert the crew, but can still be reached by handheld fire extinguishers. A Class C compartment — the most common type — is one which cannot be seen nor reached by crewmembers, and therefore must have a smoke alarm and a built-in fire extinguishing system. And finally, a Class D compartment was the same as a class C compartment, except equipped with a fireproof liner which should, in theory, cause a fire to starve itself of oxygen without any requirement for a smoke alarm or crew-activated extinguisher. The forward cargo compartment on the DC-9 was a Class D compartment, and was supposedly protected by its airtight construction and fireproof liner.

The problems with this design classification in the case of flight 592 are immediately obvious. Because the fire produced its own oxygen, the compartment’s airtight construction was rendered meaningless, and the fire eventually grew hot enough to overcome the fireproof liner, allowing it to spread to critical aircraft systems.

But this was not the first time the NTSB had raised the alarm over this fundamental failure of the concept behind Class D cargo compartments. In 1988, an American Airlines MD-83 experienced a fire in a Class D cargo hold while on final approach. Although the plane landed safely and the passengers were evacuated, the fire did not self-extinguish. The NTSB found that the blaze was triggered by a chemical reaction between hydrogen peroxide and a sodium orthosilicate mixture which were being transported improperly. The reaction produced oxygen as a byproduct, allowing the fire to grow in defiance of the Class D compartment’s built-in protections.

Following this incident, the NTSB recommended that the Federal Aviation Administration mandate smoke alarms and fire extinguishers in all Class D cargo compartments. The justification was simple: it is unconscionable to allow a fire to burn aboard an aircraft without some means of alerting the crew. However, the FAA declined to act, arguing that the proposal’s $350 million price tag outweighed any safety benefit. In its report on the ValuJet crash, the NTSB slammed this decision as short-sighted and wrong. Had such a requirement been implemented, the pilots of flight 592 probably would have discovered the fire prior to takeoff, and the crash would have been avoided. For that reason, the NTSB took the rare step of not only citing the FAA’s failure to act on its recommendations as a contributing factor, but as a direct cause of the accident.

In 1998, two years after the crash, the FAA took firm action, eliminating Class D compartments altogether. Today, every inaccessible cargo and baggage compartment on every airliner is equipped with a smoke alarm and fire extinguisher. But the changes came too late for the 110 passengers and crew aboard flight 592, whose needless deaths were brought about by the FAA’s inaction.

◊◊◊

At the same time as it pursued this line of inquiry, a different team of NTSB investigators was racking up hours at SabreTech in Miami, attempting to piece together how the oxygen generators ended up on flight 592 in the first place. According to their manufacturers, oxygen generators are considered hazardous materials, which require special authorization to be carried aboard an airplane. ValuJet was not certified to carry any type of hazardous materials, and definitely not volatile chemical oxygen generators. However, there was, and still is, considerable controversy over whether or not anyone at ValuJet knew the generators were on board flight 592. ValuJet executives initially claimed that the company did have the right to transport hazardous materials as long as they were company property, apparently hedging their bets to ward off any accusation that the airline knowingly carried unauthorized cargo. ValuJet’s company policy backed up these statements, but the FAA disagreed, noting that the “company material” rule was inconsistent with the terms of ValuJet’s certificate, and the provision was swiftly removed.

In the NTSB’s opinion, however, ValuJet most likely did not know that the oxygen generators were on board one of its planes. No company document acknowledging their presence was ever found, and no one at SabreTech could recall ValuJet asking, or giving permission, for the generators to be returned. However, a victim advocacy group argues that ValuJet did in fact make such a request several months earlier, citing the airline’s original instructions to SabreTech regarding the oxygen generator issue. The text of the order read, “From the Passenger Unitized Oxygen Insert Assy. Unit, remove the existing Insert-Bracket Assy. and the Oxygen Generator. Tag and return to stores.” In the opinion of the advocacy group, this meant that ValuJet wanted the expired generators to be returned to its main stockroom in Atlanta. However, the order does not clearly specify whether “stores” refers to SabreTech’s stores or ValuJet’s, and the NTSB apparently did not consider this to be proof that ValuJet asked for the generators back.

ValuJet was, of course, responsible for knowing what it was putting onto its planes, and in this area it failed miserably. The label “Oxy Canisters — ‘Empty’” should have caused the cargo handlers, who had received hazardous materials training, to take a closer look, because officially there is no such thing as an “oxygen canister.” Had anyone actually looked inside the boxes to determine what was meant by “oxygen canister,” the presence of the generators would have been discovered. Instead, ramp workers simply loaded the boxes onto flight 592 without any knowledge of what was really in them or why they were being transported. That such a cargo could be placed aboard a ValuJet plane without ValuJet’s knowledge was hardly the get out of jail free card that ValuJet executives pretended it was.

The beginning of the sequence of events was also ValuJet’s responsibility, not SabreTech’s. According to their contract, ValuJet should have provided SabreTech with safety caps for the generators back when it originally issued the work order, rather than leaving SabreTech to search for its own. But once SabreTech personnel became aware that the required safety caps were not present, nobody seemed to be particularly broken up about it. The mechanics and their supervisors appeared to collectively decide that it wasn’t a big deal that the generators didn’t have safety caps, and that if it became a big deal later, someone else would find some. This mentality extended even to the inspector, who signed off on the work card despite knowing that the caps were not in place. In interviews with the NTSB, the inspector said that he was primarily concerned with whether or not the new airplane was airworthy, and that the question of what had been done with parts removed from that plane barely even crossed his mind.

In effect, the removal of the parts from the airplane placed them out of sight and out of mind of the people who knew what the generators were and what they were capable of. Certainly none of them imagined that the generators would be placed back on an airplane again in the future. And in that environment of neglect, the generators were allowed to fall into the hands of untrained personnel who didn’t know what they were and didn’t know any better.

A number of structural failings at both SabreTech and ValuJet allowed this to happen. For one, there was a shocking lack of communication between the workshop floor and the shipping department, which resulted in the generators being improperly labeled. The NTSB noted that almost all other similar repair stations had a clear requirement to inform shipping staff about what they were shipping, but that SabreTech inexplicably did not. Secondly, the generators might never have ended up in the shipping area had they been properly tagged as hazardous waste, but the work card provided to SabreTech by ValuJet did not explicitly label them as such. Although McDonnell Douglas’s standard work card for removing oxygen generators gave specific disposal instructions, ValuJet’s version of the work card omitted these steps, except for the requirement to install safety caps. The NTSB noted that the same work card at other airlines did clearly identify the generators as hazardous. And the generators themselves, while printed with warnings about excessive heat, did not indicate that they were legally considered hazardous waste once removed. SabreTech did possess a DC-9 maintenance manual which mentioned that the generators were considered hazardous and provided disposal instructions, but this chapter in the manual was not referenced on the work card, so it was unlikely that anyone would have looked at it.

The low probability that anyone at SabreTech would have searched the manual for references to oxygen generators represented a reality created by the system in which the mechanics lived and worked. Although such information is, in principle, available, much of it simply sits in binders in offices, and even when mechanics do look at it, they don’t always interpret it in the way its authors intended. In an article about the crash of flight 592, famed aviation author William Langewiesche argued that the engineers who wrote the work cards used by the SabreTech mechanics were writing for themselves, not for their actual audience. The use of specific terms to describe potential conditions of the oxygen generators created a network of meanings embodying different combinations of “expired/unexpired” and “expended/unexpended,” each of which had different safety implications which the end user was expected to understand. An expired but unexpended generator needed to be treated differently from one which was unexpired and expended, or expired and expended, or unexpired and unexpended. None of this was explicitly spelled out, but was to be deduced solely from the phrase, “If generator has not been expended, install safety cap over primer.” Langewiesche’s argument was that mechanics making near minimum wage, many of whom spoke English as a second language, would not have instinctively developed the whole network of meanings built into that phrase by the engineers who wrote it. In his essay, the argument came across as somewhat condescending, but at the end of the day he was probably not wrong that a more explicit description of what an expended generator looked like, how it was different from an expired generator, and why that difference was important, might have led mechanics to take the danger more seriously.

◊◊◊

Following the discovery of negligence on the workshop floor at SabreTech, the Federal Aviation Administration conducted a special inspection of the company’s Miami facility, which found numerous discrepancies in nearly every area of their operation, including missing training documents, training which was not conducted, improperly labeled aircraft parts, containers of unidentified fluids lying about the workspace, improperly calibrated tools, and out of date manuals. As a result of bad publicity stemming from both the crash and the FAA inspection, SabreTech’s customers fled, and it was forced to shut its Miami repair station in January 1997 for lack of business. SabreTech’s Orlando facility was forcibly closed by the FAA after violations were discovered there as well. And on top of this, SabreTech was ordered to pay $9,000,000 in restitution to the victims’ families for its role in the crash.

On the basis of these findings, ValuJet sought to place blame for the accident on SabreTech, arguing that it was SabreTech’s responsibility to handle the oxygen generators properly. However, according to the rules of the aviation industry, it was (and is) the responsibility of any airline to ensure that its contractors are carrying out contracted work in accordance with applicable airworthiness standards. ValuJet’s oversight of SabreTech — or lack thereof — thus became another focus of the investigation.

ValuJet’s oversight of its contractors was based on a network of “technical representatives,” embedded within contract repair stations, whose job was to ensure that work was done on time and in accordance with the contract. Although they did perform “spot checks” in order to assess the quality of the work, this was not their primary mission. ValuJet did not take much interest in whether its contractors were complying with regulations, as long as the job got done. As evidence of the low priority ValuJet placed on its contractors’ level of safety, it was discovered that the airline conducted an audit of SabreTech in February 1996, but found only minor discrepancies, despite the major problems later discovered by the FAA. Nevertheless, ValuJet followed up in March and found that many of the discrepancies had not been corrected. The airline requested a written response to its findings within ten business days, but by the time of the accident — several weeks after the request was submitted — SabreTech still hadn’t replied, and ValuJet didn’t seem to care.

Just as important as ValuJet’s failure to exercise oversight of SabreTech, in the NTSB’s opinion, was the FAA’s failure to properly oversee ValuJet. Oversight of ValuJet was the responsibility of the FAA’s Atlanta Flight Standards District Office (or FSDO, pronounced “fizdo”), whose staff also conducted surveillance of air carriers throughout the southeastern United States. In charge of overseeing ValuJet’s maintenance program was a Principal Maintenance Inspector, or PMI. In the year before the crash, the PMI for ValuJet had expressed concern to the Atlanta FSDO that he did not have enough staff to keep tabs on ValuJet’s rapid growth, which was causing an elevated workload. The Principal Operations Inspector, or POI, agreed. ValuJet was training 40 new pilots a month, and he and his single assistant had to check out every single one of them, a task which occupied his assistant almost 24/7. The manager of the Atlanta FSDO consequently wrote a memo to his immediate superior requesting additional staff for the oversight of ValuJet — only to be rejected. His boss replied that according to the FAA’s current staffing model, which based personnel numbers on the number of planes in an airline’s fleet, the current contingent assigned to ValuJet was not only good enough, but maybe even too large. This rejection and the model which prompted it took no account of the fact that ValuJet was expanding rapidly, presenting unique challenges for FAA inspectors beyond those involved in the oversight of a normal airline.

Nevertheless, there were people within the FAA who continued to raise the alarm about ValuJet. In February 1996, the FAA’s Office of Aviation Flight Standards submitted a special internal report expressing concern that ValuJet’s operations were unsafe. Since its founding in 1993, only 27 months earlier, ValuJet had racked up 46 regulatory violations, including 20 which were still unresolved at the time the report was written, and the airline was suffering an accident rate 14 times higher than the nationwide average. The authors of the report, clearly alarmed but sticking to FAA jargon, wrote, “Consideration should be given to an immediate FAR 121 re-certification of this airline.” In effect, they meant that ValuJet should be grounded and forced to undertake reforms before it could get its certificate back. And yet, for reasons which were never determined, the report was not seen by anyone at the Atlanta FSDO until after the accident, and ValuJet was not grounded.

It does not seem coincidental, however, that eight days after the submission of the report, the FAA directed the Atlanta FSDO to initiate a 120-day period of intensive surveillance of ValuJet, citing the company’s high accident rate, its abnormal rate of service difficulty reports, its rapid growth, and its large number of third party contracts. This special inspection was still ongoing when flight 592 crashed on May 11.

In hindsight, the NTSB felt that the FAA was ill-prepared to handle ValuJet’s contract-heavy business model. The FAA was set up to monitor traditional airlines whose operations were headquartered in a single, centralized location, whereas ValuJet’s contractors were spread all over the country. SabreTech, for instance, was the responsibility of a completely different branch of the FAA which did not routinely communicate with the Atlanta FSDO at all, and which was equally understaffed. The PMI responsible for SabreTech was also overseeing 30 other certificated entities, including 20 other similar repair stations, as well as a commercial airline with 24 airplanes. His workload was so high that he hadn’t managed to complete a single inspection of SabreTech’s Miami facility since ValuJet began contracting the company’s services. He was also not included in the communications loop when, on February 29th, the POI and PMI for ValuJet wrote a letter to the company president warning that, “It appears that ValuJet does not have a structure in place to handle your rapid growth, and you may have an organizational culture that is in conflict with operating to the highest possible degree of safety.” It was the closest the FAA could come, in its stilted, bureaucratic language, to accusing ValuJet of profiteering at the expense of lives.

Those lives had unfortunately already been lost by the time the FAA wrapped up its special inspection on the 16th of June. The damning inspection made 412 findings related to the airworthiness of ValuJet’s airplanes, and additional serious discrepancies were found at some of ValuJet’s contractors, including one which could not even prove that its mechanics were trained to maintain DC-9s. Two days later, the FAA withdrew ValuJet’s certificate, grounding the airline indefinitely. ValuJet was placed onto the airline equivalent of a 12-step plan, during which it was forced to significantly downsize and undertake major organizational reforms. By the time it got its certificate back, it had far fewer aircraft, fewer contractors, and a completely new management structure. It was also slightly poorer, having been ordered by the FAA to pay $2,000,000 to the relatives of those who died on flight 592.

Although many in the public were skeptical, ValuJet did eventually fly again, taking to the skies once more on September 30th, 1996. But the profit-making magic was gone. People now associated the ValuJet name with a smoking crater in the Everglades and a reckless disregard for human lives. What was it, exactly, that ValuJet “valued”? Certainly not the lives of its passengers, was America’s collective answer.

Aware that their reputation had taken an irreversible blow, ValuJet’s management decided to pull a disappearing act: in 1997 they purchased a smaller, struggling airline called AirTran Airways, “merged” with it, and rebranded themselves as AirTran. And just like that, with a new name and a new coat of paint, ValuJet managed to shed its scummy reputation almost overnight. AirTran kept operating for another 17 years until its merger with Southwest Airlines in 2014, having carried countless passengers who would likely have been horrified to discover that they were actually flying with ValuJet.

◊◊◊

In the aftermath of the crash, SabreTech was subjected to a criminal trial for its role in the accident, and in 1999 the now-defunct company was found guilty of eight counts of causing improper transportation of hazardous materials, for which it was ordered to pay a $2,000,000 fine. Nevertheless, the only people charged in connection with the crash were three low-level SabreTech employees, who were accused of falsifying maintenance records for their roles in signing off on relevant work cards despite the absence of safety caps on the removed generators. The previously mentioned flight 592 victim advocacy group slammed this decision, claiming that prosecutors were going after “minimum wage workers” in order to avoid charging those who were actually responsible. In their view, primary responsibility for the crash lay not with SabreTech, but with ValuJet, and the fact that one was on trial but not the other represented a gross miscarriage of justice. They were right in that the decision to prosecute SabreTech and not ValuJet undermined the basis of contractual responsibility, according to which ValuJet should have monitored SabreTech as closely as it would have monitored its own personnel. As the NTSB noted in its report, the contracting party must retain legal responsibility for the actions of its contractors, or else it would be possible for an airline to avoid having to answer for the airworthiness of its own airplanes simply by transferring all liability onto the contractors. And yet, this is effectively what ValuJet did, and they got away with it.

In the end, two of the three mechanics charged with falsifying documents were acquitted by a jury, and the third never stood trial, having apparently fled the country. No one went to jail as a result of the crash of flight 592, although many people felt that someone should have. It could be argued that the most guilty parties were those at the highest levels of ValuJet management who pioneered its business model. A strategy of growth at all costs using aging, second-hand airplanes maintained by a murky network of contractors laid the groundwork for an accident, no matter what form it eventually took — after all, under such a system, things inevitably slip through the cracks. And yet creating the circumstances for an accident to occur, as ValuJet’s leadership undoubtedly did, is not a crime, and even if it were, it’s difficult to see how one would prove it in court. This is one of the realities of such a complex system: that when the system itself results in an accident, those who shaped the nature of that system are often so divorced from the accident’s proximate causes that any culpability dissolves into a fog of uncertainty. William Langewiesche perhaps put it best when he wrote, “Flight 592 burned because of its cargo of oxygen generators, yes, but more fundamentally because of a tangle of confusions that will take some entirely different form next time. It is frustrating to fight such a thing, and wrongdoing is difficult to assign.”

◊◊◊

The flight 592 advocacy group claimed in 1999 that the failure to prosecute anyone meant that safety lessons were not learned, but looking back a quarter century later, this assertion thankfully turned out to be false. In addition to the retrofit of all Class D cargo compartments, numerous other safety initiatives were undertaken. Work cards were rewritten to clearly identify oxygen generators as hazardous waste. Transport of oxygen generators as cargo aboard an airplane was prohibited, and modifications were made to the generators to more clearly indicate the danger and mitigate the consequences should they be accidentally loaded onto a plane. Although incidents continued to occur — at the time of the publication of the NTSB report, the FAA was investigating 14 cases of oxygen generators being transported aboard airplanes since the crash of flight 592 — the crackdown was swift. In one of these cases, a repair station called Santa Barbara Aerospace shipped 37 improperly packaged oxygen generators aboard a Continental Airlines flight; disaster was avoided only by chance. Notably, this was the same Santa Barbara Aerospace which was cited for the improper installation of the in-flight entertainment system which brought down Swissair flight 111 in 1998, for which the company was shut down by the FAA — no doubt as a cumulative result of its repeated violations, including but not limited to the oxygen generator incident. But despite these high-profile violations, most companies learned their lessons, and the changes to generator design have proven effective, as there hasn’t been another serious aircraft fire caused by improper transport of oxygen generators since the crash of flight 592.

Within the FAA, the crash also led to major structural reforms. The head of the FAA was forced to resign, and the agency launched a 90-day internal safety review which prompted changes to its staffing policy in order to allow effective oversight of unusual or rapidly-growing air carriers. Additionally, $14 million in new funding were allocated to the FAA’s hazardous materials enforcement program in order to increase the number of personnel who were actively involved in combating dangerous shipments. However, one of the most touted changes as a result of the crash was also one of the least impactful. Following the accident, Congress reworded the FAA’s so-called dual mandate — its simultaneous responsibility for both promoting air travel and ensuring its safety — by removing the “promotion” clause from the agency’s mission statement. In practice, this was political theater, as the only things which changed were the words. The FAA’s actual mission, which is to enforce existing regulations and balance new ones against the realities of the market, remains the same as before. In fact, so little has changed in this regard that calls for the removal of the dual mandate are still heard rather frequently, even though on paper there has been no dual mandate for over 20 years and counting.

◊◊◊

Twenty-six years on, the crash of ValuJet flight 592 remains one of the most infamous chapters in recent US aviation history — a story which captivated the public, triggered widespread outrage, and undermined faith in air travel as a whole. Nevertheless, in the years since, low-cost airlines which are superficially similar to ValuJet have proliferated around the world, and the flying public has by and large embraced them. In that sense, ValuJet, by being the first, provided its countless successors with a shining example of what not to do. In the Western world, this example appears to have been taken to heart, since low- and ultra-low-cost airlines in Europe and North America now have a safety record equal to and sometimes even better than that of the legacy carriers. Even those with rather scummy reputations, such as the Las Vegas-based Allegiant — an airline run, ironically, by one of the co-founders of ValuJet — have, almost without exception, avoided any serious accidents, let alone catastrophes on the scale of ValuJet’s.

And yet, the horrific fate of flight 592 and its passengers continues to haunt us, always hovering in the background whenever we encounter a new airline offering cheap tickets and no-frills service. There is something especially horrible about the way they died, lured onto that old blue and white airplane by hard economic realities, only for their final moments to be filled with unimaginable terror. Did they regret choosing to fly with ValuJet? It was not their fault, but they probably did. And perhaps so too did Richard Hazen and Candalyn Kubeck, who fought to save their stricken plane until the very end, only for that end to come so shockingly fast that they barely had time for heroics. What did they die for? We know that the answer is nothing — but at least a handful of shareholders somewhere got good value for money.

_________________________________________________________________

Join the discussion of this article on Reddit!

Visit r/admiralcloudberg to read and discuss over 220 similar articles.

You can also support me on Patreon.